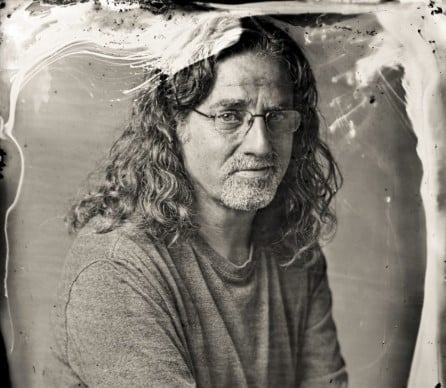

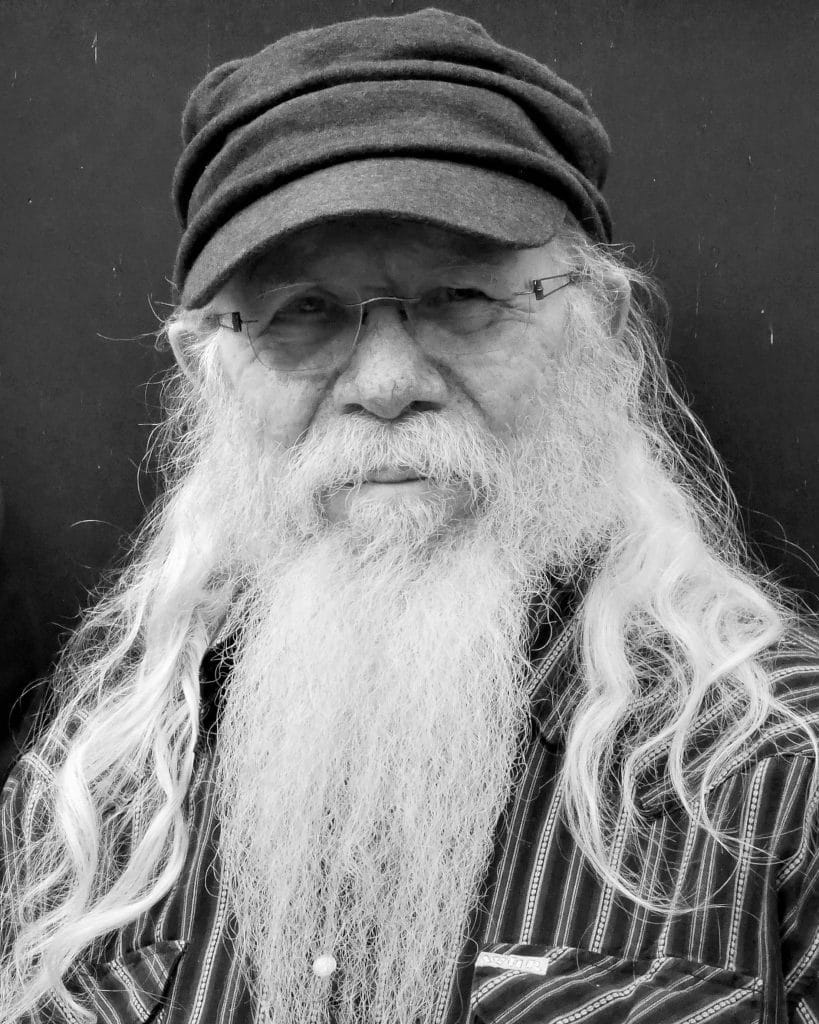

One came up in the gritty blues clubs of Chicago, the other found the eye in the maelstrom of early alternative rock– but Kirk West and Jay Blakesberg took rock photography to a new level while traveling and documenting the music of their respective heroes. For West, his time with the Allman Brothers Band began in the early ‘70s as a fan before evolving into the position of tour manager when the ABB reunited in 1989. Jay Blakesberg was a teenager when he first saw the Grateful Dead. That experience would create a lifelong enthusiast, a veritable visual authority on the Dead, and one of the most sought after photographers in rock n’ roll.

The motto for both men has always been “Have camera, will travel”, and their stories are as rich and detailed as the images they’ve captured. On March 18th, the two friends will treat visitors to Gallery West with a free, informal lecture that’s sure to entertain and enlighten fans and aspiring photographers. Need a preview? Yeah, I thought so…

AI- Jay, you shot your first Grateful Dead show… What was it, 1978?

JB- Correct.

And you were there as a fan– or were you there working?

JB- I was there as a fan. I was a 16-year-old kid. My Dad loaned me his camera… I brought my camera and got a couple of okay photographs… I remember I actually sent the film out through the local camera store to get it developed. And then I printed them in my darkroom basement that I had built. For me in the early days, I was just taking pictures for fun and to make 8×10 prints and give it to my friends and some to tack onto my bedroom wall– and that was the extent of what I was trying to do.

Jump forward a little bit. You got out of college, you got a gig as a house photographer out in San Francisco for a bunch of different clubs. I don’t even know if a lot of clubs even still do that. And how important was that to you– I didn’t mean this to be a pun– but how important was it in your development?

JB- It’s funny because nowadays every venue and every club has multiple staff photographers. The photography game has changed so much, but you know, with social media, everybody wants photos right now. “Right now! We want to put them up right now!” So back then it was like convincing somebody they needed a house photographer was a lot harder because there was no social media and there was no immediate use, but it was sort of like– and nobody was paying me anything– “I want to come there. You’re going to give me access. I’m going to get pictures. You guys can have them if you need them for something.” I remember shooting a Butthole Surfers show and then they ended up using one of my photos on a poster for the next time the Butthole Surfers played. The club I was sort of the “house photographer” for was a club called the I-Beam and it was on Haight Street– and it doesn’t exist anymore, obviously. Actually, the building was knocked down many years ago. But mostly what they were doing at the I-Beam, they were doing the birth of alternative rock. I saw Jane’s Addiction there and Soundgarden and The Pixies… Just so many different bands like that. A lot of punk bands, the Meat Puppets, and Primus… So back in the late eighties, when I was trying to figure out how to become a professional photographer, nobody cared about the Grateful Dead. If I went to a show, like a Butthole Surfers show for instance, and I tried talking to the person standing next to me about [how] I was going to go see three Grateful Dead concerts the next week or the next month or whatever, they would look at me and like I was an alien, you know? At that point, there was a huge division in music fans. Nowadays everybody’s got ‘big ears’, right? Everybody listens to everything. You’ve got people that are Deadheads into the Allman Brothers that are also listening to the Chili Peppers and hip hop and EDM and the list goes on and on. But back then, first of all, there was no other jam band except for the Grateful Dead and the Allman Brothers. The term jam band didn’t exist as a genre…

Were y’all using that term at that point?

JB- No, no, they weren’t. I don’t know the year, but the term jam band was coined by a guy named Dean Budnick who’s an editor at Relix magazine. And I want to say that was somewhere in the early ’90s when that all kind of happened…

KW- Yeah, that was around the Wetlands [Preserve Club] time.

JB- Yeah, exactly. Even though I was shooting the Grateful Dead, and I was a Deadhead, I knew that as a professional photographer, I couldn’t rely on just shooting this one band to try and even remotely make a living. And so, you know, the birth of alternative rock was exploding– grunge and Pearl Jam and Nirvana, and the list goes on and on… And I dug that stuff. I mean, the energy in the room when those bands would play was off the charts! So to be in the front row being smashed against the stage by people that are moshing and stage diving. I have pictures of Chris Cornell and Soundgarden stage diving and crowd surfing in the tiny club, the I Beam, on Haight Street!

KW- I was doing exactly the same thing except I hated that music! (Laughs)

Kirk, I was going to ask you the same thing but with a twist. During your time in Chicago working for the newspaper, how important were those regular assignments and were there times when you were just like, “Oh man, I’ve got to go take pictures of that guy?” Did that hone your ability?

KW- Well, I was working at a little co-op of photographers and nobody was making any money. It’s just like, Jay. We’d go in there and we shoot– and you’d bring an envelope filled with 8x10s to give to the guy at the backstage door or the front of house security… And you could shoot! It was the same kind of thing. It was basically the same kind of time frame. I was just a hippie boy with a camera until I got back to Chicago in ’77! I had quit doing dope, and I’d quit drinking so I could focus better– and I had more of a drive rather than just snapshottin’ my life. In Chicago, we had five or six guys that kind of threw in together, had the same phone number and worked out of the same little co-op shop. And we had some New Wave guys. We had some punk rock guys. We had a guy that liked to shoot strippers and supper club singers! I was doing blues and country and then we’d all, you know, we pulled the short straw to see who got shoot Springsteen or the Stones or whatever. The thing that got Jay off so much with that New Wave, punk stuff was exactly what sent me running. (Laughs)

JB- For me, the energy in those rooms when those bands were playing was just so intense and so great– and I dug it! But at the same time, those were the bands that the magazines that I was submitting photos to wanted to run, and those were the people that were paying me money– even if it was $25 or $50 or $75. I lived in a house in Oakland, California. I had five or six roommates. My rent was $150 a month. So if I can make $300 a month or $400 a month taking pictures, I could pay my bills and throw in $10 a week for food so we could eat burritos. I mean, I was, the definition of a starving artist– as probably was Kirk at the same time– but I was 10 years later.

Kirk, when did you first shoot the Allman Brothers?

KW- First time I pointed a camera at ’em was in 1973 at Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco.

And were you a fan of them at that point? Had you guys met yet?

KW- Oh, f–k yeah! I had seen the band play about a dozen times before Duane died in late ’71. I was a huge fan.They were my favorite band. But I had just sobered up… ’73, I had just got off the dope and s–t, so I started to travel a bit, and it was just buying a ticket and going in. Back then there were very few rules for photographers. They didn’t control access the way they do now or even 10 years later. It was being discreet, getting yourself in those situations… Plus, I spent lots and lots of times in Chicago shootin’ blues clubs, shootin’ the old honky tonks. The access was easy, as you can imagine. You end up in the basement of a blues club– but sitting at the feet of Muddy Waters!

I was going to ask this a little bit later, but what has technology done for or against the rock photographer in the 21st Century?

JB- Well, first of all, technology, of course, is the great disruptor, right? I mean, look what it’s done to the film industry, the music industry, the same with the photography industry. Realistically what technology has done to the photography industry… It has created a world of mediocrity because the bar has been lowered so far, right? You used to need to be an artist and a technician, you used to be able to actually know how to expose the film properly, right? A good eye and expose film, right? Nowadays you can take a picture with a digital camera, look at the back and say, “Too dark. Let me make it lighter. Too light. Let me make a darker.” Right? The problem is the bar is so low now and there’s so much mediocrity out there– and then the cell phone thing adds to the clutter of the Internet– that unfortunately, we live in a world where most people only are able to recognize mediocre photography. And I’ll call it mediocre art. And the problem with that on the next level is that art is what inspires us to be better and to create better imagery. So if all people are looking at is bad art, bad photography, how can you be inspired to make good photography?

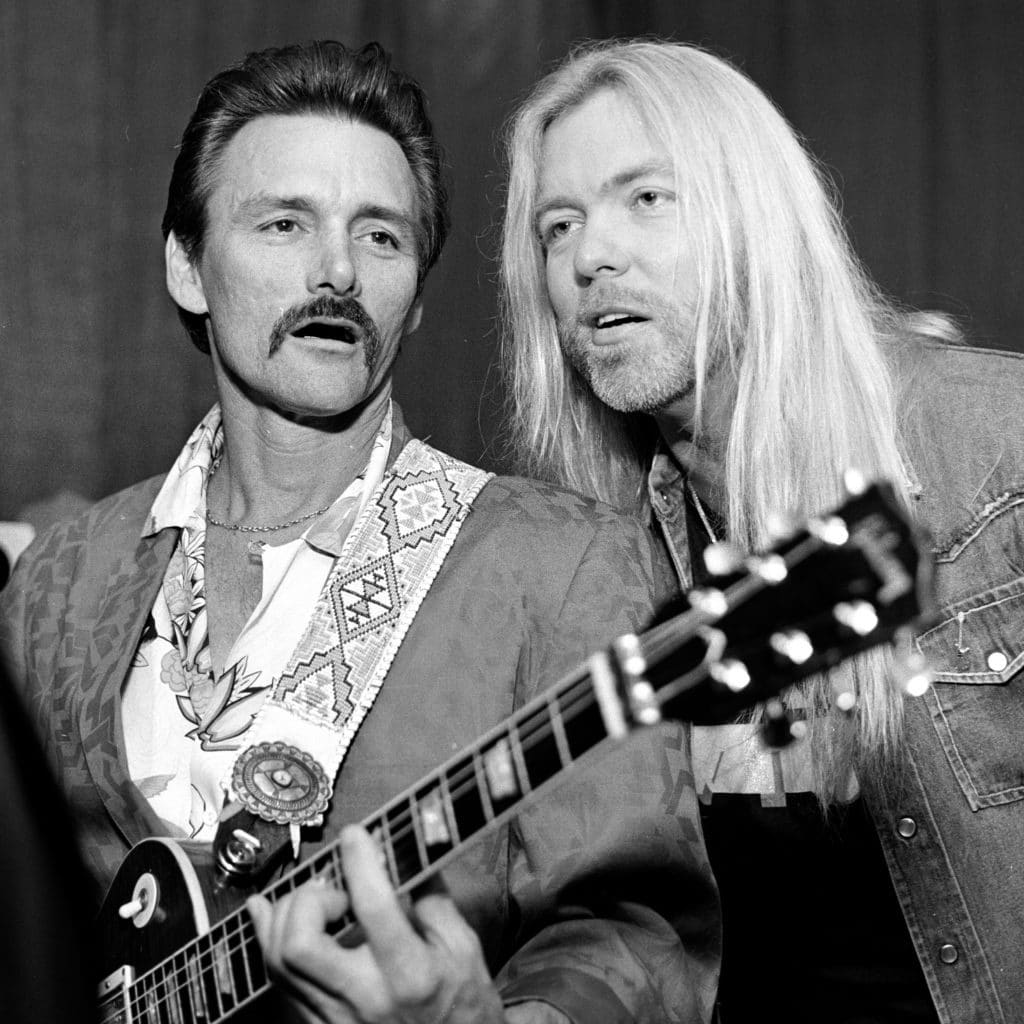

Kirk, the picture you took of Gregg Allman and Dickey Betts from Madison Square Garden in 1986. You say that was the moment that led to the eventual Allman Brothers Band reunion ’89. You were there taking pictures. How did you get into the position of tour manager?

KW- Several things came into play. In ’88, Polygram records had just put out the Eric Clapton Crossroads box set, and it was the first rock box set that I was aware of. It was a massive four-CD package that covered his whole career. Polygram had taken over the Capricorn tapes archive. They had a bankruptcy… Anyway, Polygram ended up with all the Capricorn tapes and they decided that they wanted to do an Allman Brothers box set. So I just raised my hand. They went around to all the brothers’ managers– there was no band at that time in ’87, ’88. My name kept coming up. So Bill Levinson reached out to me from Polygram. He was real cautious because a lot of the Clapton nutcase fans came and offered their help when they were doing Crossroads, and he said they were more trouble than they were worth. So he was hesitant and he said, “The next time you’re in New York, let’s get together and talk about it.” I booked the plane that next day, and I got involved! I was associate producer of that box set. It came out in the spring of ’89, and during that same couple of years– ’87, ’88– Dickey and Gregg were both signed to solo deals with Epic Records. The idea was… Let ’em do a couple of solo records that won’t sell– and then we’ll have ’em both under contract and put an Allman Brothers Band back together! ‘Cause that’s where the money was. Well, that kind of worked out, and I was just out there to shoot, you know, still basically doing the same thing– riding the bus, they weren’t paying me, but they were covering my travel expenses and hotels and stuff. And I was free to sell my stuff to anybody, but it was primarily going to be for them. I was out there on the road just to shoot pictures for three weeks, and they’d hired a freelance tour manager who was young, worked with those bands that Jay like so much and thought if he talked loud, he could get Dickey and Gregg and Butch to move faster. And that lasted for three days. Dickey came to me and said, “Listen, if that son of a b—h talks to me like that one more time, I’m going to cut his tongue out of his head! So we’re going to hire you to be his assistant. If he wants us to do something, he’ll tell you, you come tell us ’cause you know how to talk to us.” I told him, “I said I don’t know anything about tour managin’, man. I shoot pictures!” And he said, “You’ll learn.” They get rid of him at the end of that three-week leg and kept me on as the assistant tour manager for a year and a half. And the guy they hired to replace him, they made him their manager. And so they moved me up to step ladder, and I stayed in that role ’til 2010– so a good 18, 20 years!

You were documenting and taking pictures the whole time, right?

KW- Yeah, yeah.

Let me ask you both– because you were basically tasked with documenting the lives of bands on the road. Jay, you had the Dead, Kirk you had the Allman Brothers. How do you become that ubiquitous eye that catches everything?

JB- Always have a camera with you.

KW- Yeah. And know when not to put it up to your face! Once I got autofocus on digital, I shot a lot more! I’d use a wide-angle lens in the camera at my waist and just shoot around the room in those kinds of moments. But you’ve got to know when to shoot and when not to– but always have it in hand, you know? Haynes said something really interesting in the forward to my Brothers’ book– and I know Jay’s got the same thing. You just have an uncanny instinct when the moment’s going to come– and you know that you can’t stay there. You get the moment, you get the shot, and then you back away!