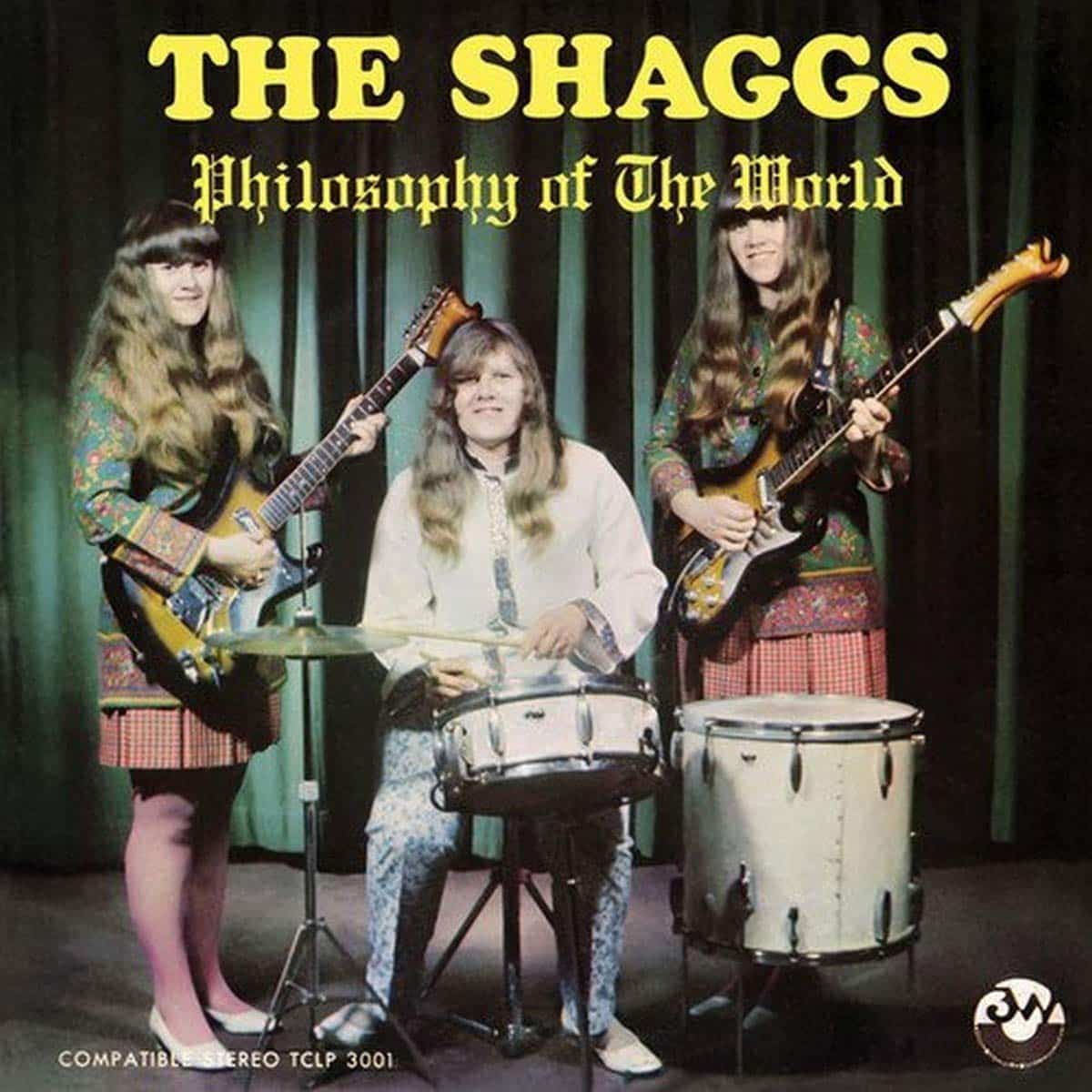

In the late 1960s, three teenage sisters– Betty, Helen, and Dorothy Wiggins– each took up an instrument, and under the “guidance” of their father, Austin, formed The Shaggs. Never specializing in competency, The Shaggs were a band forever developing in real time. With the misguided hubris of a charter school parent, Austin urged his daughters into a recording studio, telling the sound engineer, “Get my girls while they’re hot.” The result was their infamous debut, Philosophy of the World, an album perhaps revered more for its novelty than its content.

Their songs, although barely in tune or time, glimmer with a youthful naiveté and innocence. The Shaggs were no Shangri-Las. Instead of decrying authority, The Shaggs sang about God, family, and lost cats. A song named “That Little Sports Car” might promise speed and escape, but in the hands of the Wiggins, it’s a chance for moral edification: “I learned my lesson never to roam.”

“It’s Halloween” doesn’t dwell on the gory details, but celebrates costumes, pumpkins, and playfulness. Fan favorite “My Pal Foot Foot” captures the familiar childhood anxiety of searching for a lost pet. Love songs like “What Should I Do?” and “Sweet Thing”, with the chilling final line, “You’ll never make me dream,” take a darker turn, with lyrics that aren’t typical of teenagers mining Top 40 fakebooks for inspiration.

Elsewhere, The Shaggs tackle more cosmic concerns. Existential tensions stir the title track, “Things I Wonder”, and “Why Do I Feel”, with its hard pill: If “You can never please anybody in this world,” then “Why do I feel the way I feel? Why do I feel the things I do?”

A cursory encounter with PotW might leave a listener questioning the album’s stature as a cult classic. How can something so rudimentary achieve a status beyond amateur hour? After all, Frank Zappa famously declared The Shaggs “better than The Beatles,” and Kurt Cobain discussed them with reverence. Part of their staying power can be attributed to their irregularity, their obliviousness to influence. They created without the burden of precedent. Even the most celebrated bands have an identifiable lineage; few like The Shaggs have the confidence to create with no obvious reference point. More so, they transcend the novelty tag because of the general wonder they have for the world. For the Wiggins sisters, naiveté and sincerity are synonymous. Their songs capture those few years of childhood when we thrive in a vacuum of awe, waylaid by the beauty of the everyday.

Because of their nonchalance and innocence, the band exuded a sense of self that allowed them to exist on their own terms, an ethos similar to the DIY spirit that’s fueled any number of outlaw music scenes. Encountering PotW in an era defined by the robotic stylings of The Voice and American Idol might be a jarring but necessary experience for contemporary artists reluctant to trust their hearts.