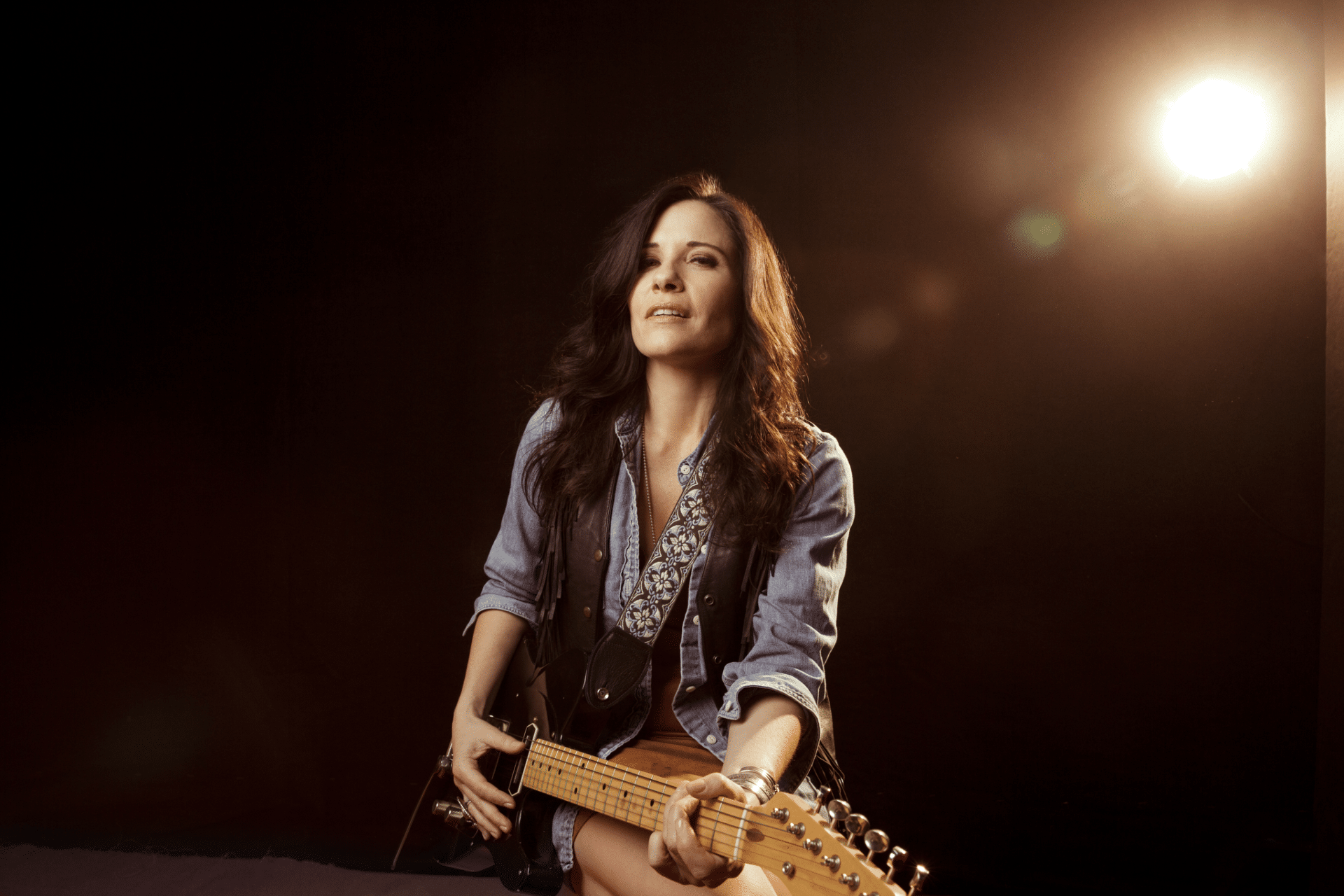

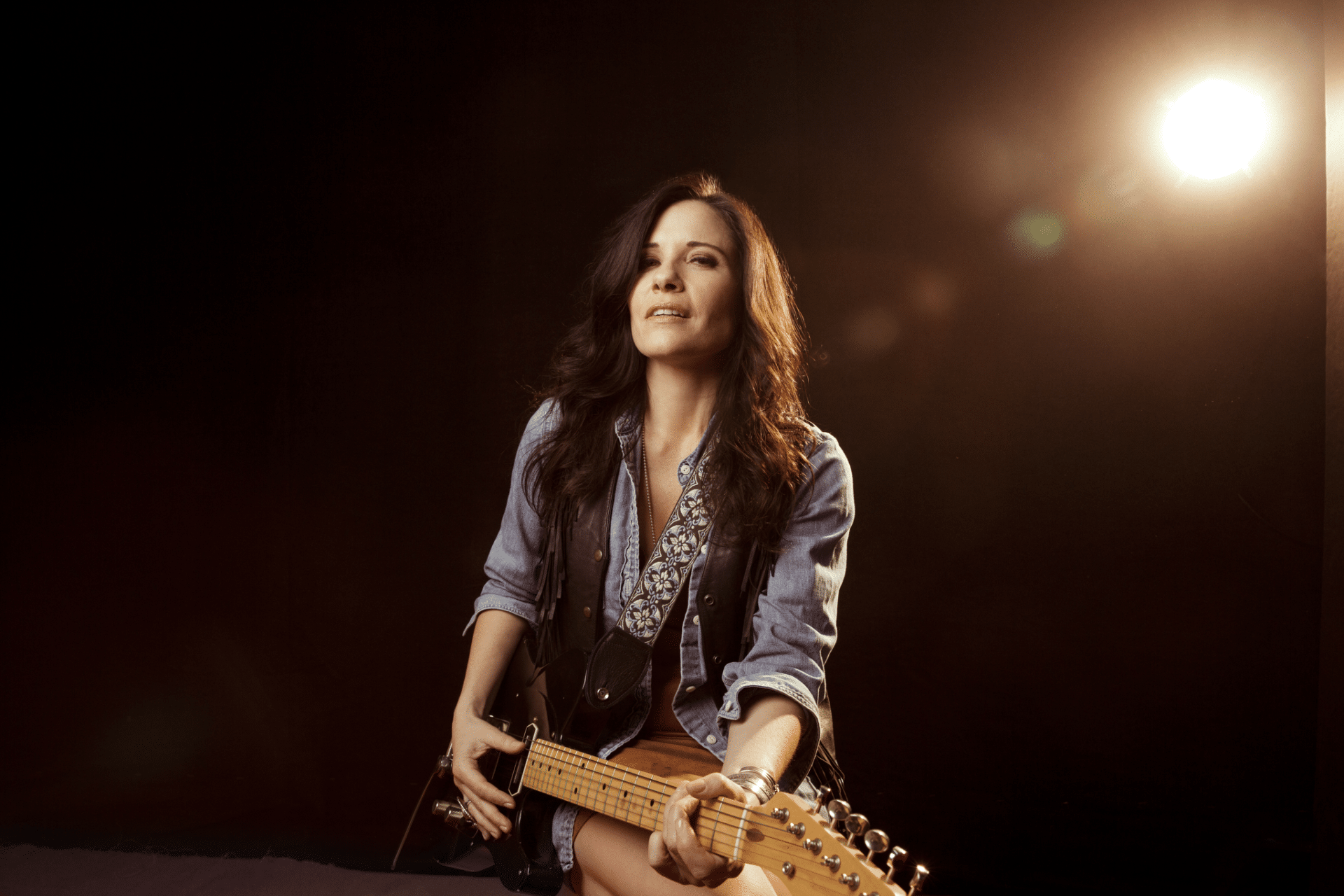

Shannon McNally is a honky tonk hero on her new album, a dream project comprised of classic outlaw country anthems and personal favorites from the catalog of Waylon Jennings. The Waylon Sessions features a superior band of country music sophisticates as well as guest shots from Lukas Nelson, Buddy Miller, Rodney Crowell, and Jessi Colter exploring the aura of one of American music’s biggest icons. Drawing on her own extensive career and experiences, McNally imbues each track with a fresh style and attitude while accessing a new dimension of Ol’ Waylon’s legend. The Waylon Sessions rolls out on May 28th. Pre-order now!

AI- Over a decade ago, I was out workin’ on the road, ridin’ through Texas and I had with me Waylon Jennings’s autobiography. I could read a few pages, I could look out the window and see some things that he described and he talked about– or at least I pretended that I could. You have also had that experience. You did that too if I’m not mistaken.

SM- Oh yeah! For one, you can still hear Waylon on the radio, which is always exciting to me! It’s always like, “Yes! Yes, alright!”

When did you initially have the idea that you wanted to make an album completely of songs that Waylon had recorded?

I guess, just about a year and a half ago? Actually, probably at this point almost two years ago. I’d always internalized Waylon and his music. I’ve been listenin’ to him my whole life, but last couple summers ago, I’d just moved to Nashville and I was invited down to a benefit night. They asked me to sing two country songs, straight country, and I could use the house band. So I did. My whole career, I’m always used to being the youngest. I always worked with people and players that were really fantastic and really experienced– and generally older than me! And for the first time ever, this band was younger than me! And they played great! They really played well! I did “Don’t It Make My Brown Eyes Blue” and a song by Terry Allen called “Amarillo Highway”, and I remember walkin’ off stage thinkin’, “Man, those guys were really good!” I didn’t know how they were gonna play, but they were really good. That was a silly thought on my part. It was just one of those knee-jerk reactions. I walked off stage thinkin’ “Man, those guys were really good. I could’ve done anything! I could’ve done Waylon Jennings!” And I was like, “Hmmmm… I wonder how that would feel on stage? I wonder how much fun that would be?” So at the end there, I just thought, “Oh, I guess that’s what I gotta do next!”

The album really does come across as generational in a few ways. You’ve got great musicians like Kenny Vaughan involved, Derek Mixon, who’s out there working these days, second-generation Bukka Allen, Terry Allen’s son– and then you’ve actually got a real live Waymore’s Outlaw in Fred Newell! And that’s not even takin’ into account all the special guest stars! Did it feel like that when you were puttin’ it all together? Bridging this gap of time between Waylon’s era and your era?

There’s three stages of making a record– the idea to make it, the prep to make it, and then makin’ it. And so the idea came pretty fast and then the prep and it was a real quick turnaround. I made the record very quickly thereafter. I had recorded it within a month of just even thinkin’ about it, which is kind of unheard of sometimes. So it really happened fast. The thing that was primarily important to me about it was gettin’ the guitars right, gettin’ the band right. I figured if I get the band right, it’ll be easy. It’ll be all right. And I wanted it to be authentic. So that’s why I called Kenny Vaughan first.

To me, it was like, “No, the guitars have to be right. They can’t be overdone. They can’t be underdone. The tones have to be right. I need people who really have thought this through.” So my first call was to Kenny Vaughan and we put the rest of the band together from there. But the basic idea that I had was the energy. Waylon’s energy is what’s so interesting to me, more so than individual songs. I thought it was kinda bold of me to do this in the first place, but because I felt that, I wanted to make sure that it was authentic right down the line, and that everybody that I called, there was a reason for them to be there. There was a reason that I called them. For the most part, it was because they were all one degree of separation from Waylon. So there was no translation necessary, you know? I didn’t have to explain to anybody what the idea was because they already knew it. On some level, I just wanted to make the experience as authentic as I could never having met him personally, not being from Texas, and (laughs) being a woman! Those three things were not so small hurdles!

That part of it, being a woman. You’ve got a quote where you say when you listen to Waylon, you hear an adult. He sounds like a grownup, and often that has been confused– being a grownup– with being a man. That’s a heck of a commentary. I think that reaches right into the heart of country music, even, especially today. Is that something that you were able to talk about with Jessi Colter as part of this project? Because if anybody would have a say so in that idea, I imagine she had a lot to say.

Oh yeah, for sure! There’s a couple of thoughts right there. I sure did. Jessi was the first person I called after I recorded the initial body of the record. ‘Cause when I went in to record it, I thought, “Well, if this goes really badly, nobody will ever hear it! I’ll just bury it and we won’t ever talk about it again! It’ll be a secret!” But it came out pretty good, and so I called Jessi and said, “I wanted you to know that I did this, and I hope you approve.” I sent it to her, and she did. She was really kind about it. But she did say, “Yeah, sister, that’s really bold!”

It is bold! I have never heard a woman sing any of this stuff. She said, “I wouldn’t have. I can’t.” So that’s impressive, and she said, “But I think Waylon would love it.” Once I heard that I went, “Alright, that’s cool.” I’ve heard so much about the legend of Waylon Jennings, and the outlaw country movement is pretty well documented. But most of the time when you hear people talking about it, it’s his runnin’ pals and his runnin’ mates and his bandmates– and they were all maniacs there for a while (laughs)! Complete and utter maniacs! And they have all their war stories and all their cowboy legends, and it’s all fantastic! But most of it is them talkin’ about it firsthand from first person. I thought, “I’d be so interested to hear what the women around him thought of him.” So I went out on a small mission to talk to the women that knew him and knew him well.

Growin’ up as a little girl in the ’70s and ’80s, I remember my feelings about him were that he was a pretty cool guy. He wasn’t your run-of-the-mill provincial thinker. Even though he was very much an alpha male, very much a 20th Century man’s man, he didn’t seem, to me, intimidated by women or threatened by women or smart women or pretty women. He seemed very comfortable and that he was a man who could have women friends. That’s not really that radical an idea, but it is kind of radical in some ways.

I talked to a bunch of women that knew him– Connie Nelson and Jessi Colter, Carlene Carter, Emmylou Harris– and they all said the same thing. They all said Waylon was fantastic. That he loved women. He had a lot of women friends, and he wasn’t intimidated by smart women. On the contrary, he surrounded himself with really fantastic women. So I felt more comfortable. The more I heard that the more I felt comfortable that this was a good idea.

You talked about that energy earlier. One of my very favorite things about a Waylon Jennings record or a Waylon Jennings song is that oftentimes those songs just keep goin’. They just run on and then they fade out and I always imagine what must’ve been going on at that session with those players just in there bein’ smoky. I’ve always been fascinated by what happened after that fade-out. I’ve only gotten to hear two of the tracks off the record. Were you guys able to let it run and explore those songs a little bit just for yourselves?

Yeah. That meant a lot to me. I didn’t want to cut these tracks too short. I do think that you gotta let the band play, particularly with the caliber of musicians that I have. All the guys that I was playin’ with and workin’ with really do come from a live setting. I come from a touring background. I love a good live show, and I love a show where like, “It’s goin’ on all night, folks! We’re gonna take three breaks!” So you stretch out, you play your favorites, you play the audience songs they want to hear, but you let the band stretch out. Sometimes just to fill the time and sometimes just because it feels good and just because people are dancin’. The idea is that you want to set a feeling, you know? Yeah, we let the band stretch out quite a bit. There’s like this automatic shutoff point where it’s like, “Okay, the jam is done now! Let’s play the next song!” But before that happens, (laughs) let’s stretch out, let’s feel good!

It’s called The Waylon Sessions, but you also get the opportunity to explore some of country music’s, American music’s greatest songwriters. You got a couple of Billy Joe [Shaver] tracks on there– “You Asked Me To”, “Black Rose”— Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night”, the great Ed Bruce and Patsy Bruce, “Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys”… Were you conscious of that as you were selecting the songs and puttin’ it together?

Mostly I was conscious of singing the songs that I like. I spent a lot of time with his catalog over the course of a lifetime, so they’re the ones that bubbled up to the surface real fast. Like “This Time”. I always wanted to sing “This Time”, “You Asked Me To”, all the Billy Joe Shaver stuff, “Black Rose”… I have always wanted to sing that stuff. Yes, I did think about [that]. There was a few things. One, what are the most important songs that capture that energy? And two, you’re immediately singing the American songbook because Waylon was a performer, he wrote songs, but he also sang whatever he wanted to sing. Like Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, or Elvis.

Also in my mind, what’s so nice about Waylon was that he had a posse. He always had friends. It was a group activity being on the road. All those guys were friends and they sang each other’s songs. They didn’t worry too much about who wrote what. A great song was a great song, and a lot of people would sing it. So yeah, I was definitely conscious of the writers, wantin’ them present, that energy present. They were his good friends– Willie [Nelson] and Kris Kristofferson and Billy Joe Shaver and the rest. I was summonin’ that energy too. I wanted it to feel like friends.

What about your peers? Other artists? And I don’t just mean the women, but the men as well. I’d wager that making an album of Waylon Jennings songs is a dream project for a lot of folks. What’s been the reaction that you’ve gotten for doing this?

I think they’ve liked it! They’ve been excited about it, men and women, because ultimately these are great songs. You pay the best tribute to an artist by transcending some level of what they did and making it your own because that’s what a great artist does. That’s what Waylon did. That’s what Willie did. They made somethin’ their own. That’s how you do the highest honor to the song and to the project. I feel really grateful that the idea manifested and that it came out of the ether and became real. I felt like I got to channel that. So on some level, I don’t even feel responsible for it ’cause it kinda came right through me.

On this other level, I’m like, “Well, I did think of it. So I guess I’m partly responsible!” (Laughs) But I feel really grateful and it’s really nice to walk around in his shoes a little bit and feel that sense of confidence. There’s a confidence that he exuded that doesn’t have to come with gender. It just feels comfortable and confident. I’m really grateful to him that he left that door open wide enough that I could come in there and do that.