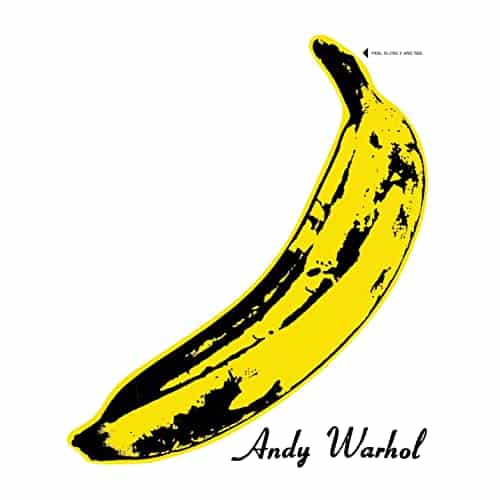

According to author Martin Amis, “It is the summit of idleness to deplore the present, to deplore actuality.” Here, Amis reminds us that reality, the here and now, is inescapable. As much as we might romanticize the past, the present overwhelms us. With iconoclastic intentions, The Velvet Underground embraced modernity with the release of their debut record, 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico.

As inventive as contemporaries like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones were, those bands had obvious American rock n’ roll and R&B antecedents. The Velvet Underground had no discernible lineage; they were a band without a precedent. True, frontman Lou Reed had roots in doo wop and had spent some time crafting novelty tunes for Pickwick Records, and secret-weapon John Cale had studied with American composers John Cage and La Monte Young, but nothing in their pedigree foreshadowed the VU’s art-damaged depth charge.

VU&N reimagines modern music’s sonic possibilities. Instead of offering another Chuck Berry rehash, the band challenges with a mix of ethereal drone, primitive percussion, feedback, and delicate arpeggios, each song foreshadowing a subgenre– the gentle dream pop of “Sunday Morning”, the glam decadence of “I’m Waiting for the Man”, the proto-punk rumble of “Run Run Run”, the jangle pop of “There She Goes Again”, and the no wave anarchy of “European Son”.

Lyrically, Reed injects new life into the R n’ R songbook, embracing the taboo, trading his street corner harmonies for lurid, yet realistic subject matter. Instead of waiting for their dates, they’re waiting for their dealers; instead of holding your hand, they’re kissing shiny boots and tasting the whip.

Released to minimal sales, VU&N’s initial impact seemed inconsequential, but the band’s singularity brought the avant-garde– the other, the forbidden, the misunderstood, the now– into the middle-American home, providing a template for the vital and pioneering.