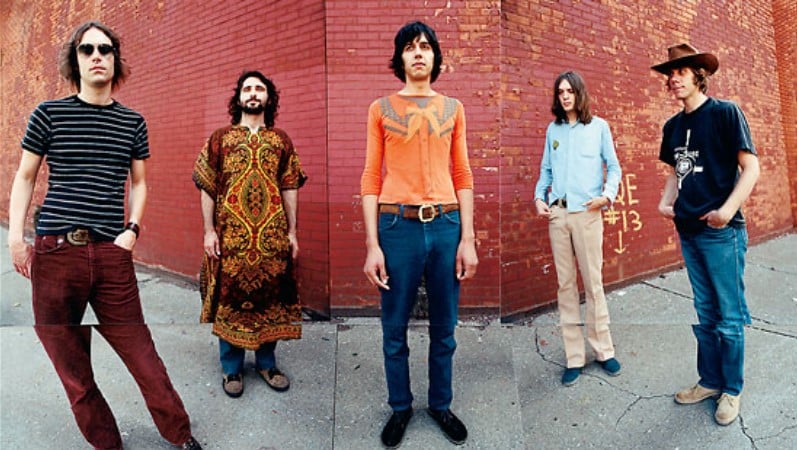

In 2001, Magnet magazine published a profile of Beachwood Sparks, who were celebrating the release of their second record, Once We Were Trees. The write-up included a photo of the group, who already resembled more a legend than a band, decked out in cosmo-country chic, looking as righteous as anything coming out of New York City. For three days, I’ve searched for poetic, even wholesome language to describe the image, but the only descriptor that works is fucking cool. The photo line-up is bookended by Neal Casal, who had recently joined the band, and Brent Rademaker, a founding member. According to Rademaker, it was Casal’s first picture with the group:

“Neal was in our picture. We were in New York playing the city. It was so cool because it was like, “Hey, is Neal gonna be in the picture in Magnet?” We said, “Fuck, yeah! He is in the band, dude. Get him over here!”

Over the next eighteen years, Casal and Rademaker maintained a friendship that saw the two flourishing creatively, together with the Beachwood Sparks– 2012’s comeback, The Tarnished Gold— and separately with countless bands and solo projects, each heart-on-the-sleeve effort solidifying their earned reputations as roots-and-beyond royalty. Whether or not they were in the same band didn’t matter; the two were never far from each other’s ears and hearts.

Casal died on August 26, 2019, at age 50, the cause suicide. He left behind a catalog of music full of songs at times heartbreaking and wounded, other times merciful and affirming, but always angelic. His solo albums alone assure his legacy– Fade Away Diamond Time, Anytime Tomorrow, No Wish to Reminisce, Roots & Wings, and Sweeten the Distance are undeniable. But perhaps he reached his widest audience with his collaborations, sharing his talents with the Chris Robinson Brother Hood, Ryan Adams and The Cardinals, The Jayhawks, Phil Lesh, Bob Weir, Lucinda Williams, The Jayhawks, and Hard Working Americans.

Casal’s music and his legacy of goodwill flourish today, thanks to the Neal Casal Music Foundation. To celebrate his spirit as a musician, photographer, and friend, the organization was established to share the gift of music, providing music lessons and equipment to students in New York and New Jersey, while also funding mental health care organizations who assist musicians in need.

The NCMF recently spearheaded the release Highway Butterfly, a massive 5-LP/3 CD set tribute that showcases Casal’s tidal wave of talent and influence across 41 reimaginings of his work. Those in commemoration include Hiss Golden Messenger, Fruit Bats, Warren Haynes, J Mascis, Shooter Jennings, Steve Earle & The Dukes, and The Allman Betts Band. Hardly a coda, the collection is occasionally elegiac, sometimes solemn, but never ominous. This isn’t the stuff of survivors’ guilt; it’s an introduction for the uninitiated, a sonic dedication to a life devoted to the arts, and a prologue to a better future made possible by Neal and those who love him.

Casal’s friend Brent Rademaker also appears, as his band GospelbeacH teams with Beachwood Sparks for a cover of “You Don’t See Me Crying”. I was fortunate enough to talk with Rademaker as he shared stories about Casal, Highway Buttefly, and his fledgling label, Curation Records. No matter where the conversation turned, Neal’s presence hovered like a blessing.

CF- Brent, I’ve been following you for years, but I hate that we finally get to talk, and it’s under these circumstances. The fans lost a favorite artist, but you lost a bandmate, friend, and brother. I appreciate you taking the time to talk about Neal and Highway Butterfly.

BR- It’s good, you know? It’s not the most ideal circumstances, but just like in Neal’s life, he was really good at bringing people together, and he’s still doing it, so I’m glad that we’re talking.

What’s it been like revisiting his catalog and seeing his name and legacy celebrated?

It’s absolutely amazing. There is a part of me that wants to say, “Hey, where were you when these solo records were out?” He was working so hard to get noticed, but that’s just on a bad day when I’m feeling a little sad about it. To be honest, we’ve been really trying to stay positive and celebrate the notoriety that he’s getting. We think it’s long overdue, and it feels really good to me. I love when I get a message or see a post about him or read an article about somebody who wasn’t familiar with Neal’s music, but through this tribute album, now they are.

It’s a lot of mixed feelings, but it’s good. It’s really good to reflect on that because it makes you reflect on your musical career. Well, don’t call it a career. If you call it a career, you don’t have one. I think that’s what they said (laughs)! It makes you reflect on your own life in music. It makes you reflect on your own friendships, your own feelings, your own depression. It’s just a rock ‘n’ roll record with forty-one amazing bands, but it does do something more, at least it does for me.

Neal and I were always campaigning for the underdog. That’s kind of what he was, so seeing the press and the positive reaction makes everybody feel good. And the thing is though, I don’t think it’s like a pity thing because the record is really darn good.

I understand the bitterness. It’s inevitable– someone dies and suddenly people are coming out of the woodwork saying they’ve lost a hero, when you’re thinking, “I’ve never heard you mention this person once.” It’s tough not to bring that resentment to the table.

It is a bit– but you know what? A lot of the bands that I love– obviously most of them– I wasn’t there in real time, like The Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers, you know what I mean? I was too young. There’s Big Star– I’m working with Jody Stephens now. He has a band called Those Pretty Wrongs, and we’re reissuing them on Curation. Big Star is a great example. People would say when I mentioned that I was into Big Star, “You’re just getting on the bandwagon.” I’d say, “No, it’s just great music.”

Everybody involved in the Neal project– if I didn’t know that they were directly involved with Neal, they’re still more than welcome. There’s no sense of ownership from me, Gary Waldman, and Michele [Augis] and Dave Schools. Everyone’s welcome to discover his music and to take part in celebrating it.

“No sense of ownership,” that’s so great. It’s not the hipster elitist, “We knew them before they got popular.” In a way, it’s a counter attitude to the bitterness.

It really helps to look at it in a positive light because it is a positive thing. If you dwell on the negative, like, “Why wasn’t he more successful, and how come he took his life?” We do think about those things. We’re not ignoring them, but that’s not what we’re celebrating. We’re not celebrating an unsung hero. We’re celebrating a friend and a musician who we admire. Me, personally, I love his songs. I love them, but I’ve been discovering more songs since I’ve heard the tribute records. There were songs that I didn’t know. It’s not like I have every Neal Casal solo album.

Have you discovered any bands through the tribute album?

Yes. I’m a big Tim Heidecker fan now. I’ve been listening to his music and comedy. I knew who he was, but I didn’t know he was a musician. It’s a two-headed dog with him for me because I wasn’t familiar with the song he did [“The Cold and the Darkness”]. It was on Roots & Wings, and that’s kind of a lengthy album for me. I had it on CD, so I didn’t listen to it a lot. But the song, I was like, “Whoa, Neal! You wrote this? Holy shit!” It’s so great. And then the other thing, I thought, “Who’s this guy singing it?” Dave told me who he was, and then I recognized him from TV and comedy. Now I’ve been listening to his stuff non-stop. And Aaron Lee Tasjan, same thing. I’m a huge fan now. I’ve been going deep into his catalog after his version of “Traveling After Dark”.

How did you and Beachwood Sparks and GospelbeacH settle on “You Don’t See Me Crying?’

I had already covered “Freeway to the Canyon” with GospelbeacH. It was pre-COVID when Beachwood Sparks were initially going to get together, and I think Chris Gunst [of Beachwood Sparks] picked “You Don’t See Me Crying.’ He wasn’t involved in the final recording because of COVID and the way you had to be there. It wasn’t a remote thing. He couldn’t travel to do it. When he mentioned that song, I thought, “Yeah, that’s not really our feel,” but it was always one of my favorites of Neal’s songs. I heard the demo of it. I told Neal how much I loved it when he was alive, from the moment I heard it till probably the last time I saw him. I really think that the words reflect so much more, something that we can relate to, like the morning that I heard that Neal was gone, and I thought about my last times that I’d seen him and talked to him on the phone. The lyrics were just an incredible reflection of what really happened, so it had to be that song. So we just nabbed it really early on, and luckily, we got to record it.

It’s from such a great album [No Wish to Reminisce].

It’s my favorite album of his.

I had it on last night– that and Frausdots [Rademaker’s 2006 post-punk record]– when I went for a walk. It was one of our first legitimate colder evenings, and they were a perfect fit for sweater and jacket weather, shuffling down the sidewalk.

Man, that’s so crazy because Michael Deming who produced the first Beachwood Sparks album also produced No Wish to Reminisce. I was sending Neal the Frausdots demos during the time that he was writing that record. I went over to his house and played him some things…

Wow…

No, seriously. He even took one of the titles for his next album from that. The thing was that there was a really big connection between me and Beachwood Sparks and No Wish. He slept in the studio in the same place that we slept when we stayed over and recorded our album. We worked with Mike Deming on that album as a producer, and then we worked on Once We Were Trees with him a little bit for some remixes. It was cool. You know, I mean, like knowing that Neal and Mike made that album together, and I know that experience they went through. He called me a lot from Studio .45 in Connecticut, and I just know he had a great time making that album, but I also know he had a hard time making it because for Neal, making records was really hard.

Is that struggle something you identify with?

Yes, then I did. Now I… That’s the thing; that’s the crazy part of the story. We always struggled making records. We had fun, and we made good records, but we always had these doubts. Neal was never happy with his records. He always told me he wanted me or us or somebody else to help him. He worked with Thom Monahan and Mike Deming, who both worked with Beachwood Sparks. He knew kind of what he wanted, and he was just never happy. It would almost taint the album for me. Then I would listen to it, and I’d say, “Oh, this isn’t that bad,” but I was really just saying, “This is great!”

During one of our last conversations in our last working relationship together, making GospelbeacH’s Let It Burn, I told Neal, “I have finally let go of that worry. I mean, I’m trying and putting forth the effort, but I’m just letting you know that I’m really satisfied. Whenever we get together and record, know that I’m really happy.” I look at it in a different way now, and he was happy to hear that. I thought that that was going to carry on for a while with him, but I think he learned that with the CRB [The Chris Robinson Brotherhood], I actually do. I think he just never got to apply it to his solo album.

How did your bands approach the cover? How did you set out to distinguish it from Neal’s version?

We wanted to “Beachwood Sparks” it. If you listen to “Silver Morning After,” “Mollusk,” or a few other songs I’ve written for Beachwood, they have a kind of country shuffle, “the desert shuffle” (laughs)! I wanted to put that feel on it, but the approach from [producer] Jim Scott’s point of view, he really drove home that even though we’re putting our own spin, stay true to the song, stay true to the lyrics, stay true to the melody. There’s so much you could do, and the two versions are very different, but if you listen, all the melodies are the same.

It’s an incredible melody. It just rolls.

It’s amazing. And I actually love our version. I hate to be like that, I’m usually not like that, but I actually really love it, even though I played bass and sang, but I mean, we did it. We might have played the song three times, and one of those was the take.

I think the piano also gives it a Zombies vibe, like something from Odessey and Oracle.

Yeah, because that’s from Jonny Neimann from GospelbeacH. That’s why it’s listed as Beachwood Sparks and GospelbeacH because that’s my partner Jonny. He’s the one who plays the piano on it, and he has a deeper and different set of influences than Beachwood Sparks. He really just ripped it to shreds. I love it. On Neal’s version, it was a guitar through a Leslie, but ours does sound a bit like the Zombies, how they weren’t just born out of psychedelia but had a basis in the standards.

But there’s also having that amazing record, No Wish to Reminisce, that I know Neal loved, and we all loved the production of it. I think in our version of Neal’s song, there’s a brightness there. It’s not very sad and maudlin. I got lucky with the falsetto thing. That’s not my style. I can’t hit that. I swear I’m glad that this was being taped because I really did feel Neal on my shoulder when I did the vocal because I was frightened. I wasn’t supposed to sing it. We were all going to sing it together, harmonies. I was very worried about it because when we were rehearsing it, I was struggling with some of the parts, but the way the microphone and the headphones and the playback was while we were recording, Jim just made it perfect. I really did feel Neal in the booth with me. I might have conjured it up.

But if there is– well not if there is– but in that other dimension, I think people can reach you. It happens all the time. I feel like he helped me because I was really scared. I mean, I’m scared just talking about it right now.

Besides his music, what was Neal’s biggest contribution to the world?

Well, that’s a good question. Neal was a person that brought a lot of spirit, comradery, and joy into the world. And celebration. If we were out having drinks at a bar or shooting pool or at a show together that neither of us were playing, Neal always had an incredible spirit and always raised the vibration. He was never a downer. He was really, really good at celebrating life and bringing people together.

It’s really hard to say because I only knew him through music, and he was kind of private, but more than most musicians, like, ninety-nine percent of them, he put others first. He helped so many other artists and so many other photographers and painters. He just brought people together.

But you know, I’d have to think about his biggest contribution. That’s all music-related, and to say he was a nice guy and brought people together is really an understatement because he was monumental in that way. You know what I mean? The connection could go on forever. You could play that “Six of Degrees of Neal Casal.”

But man, I just know for me that one of the things that could probably help answer your question was when I met him. We had never played a note of music together. We never even thought we were going to play music together. He just said he had heard the first Beachwood Sparks record, and he was a fan. I met him through a really good friend. He said, “What’s going on with you?” And I said, “Man, I’m breaking up with my girlfriend, and I think she’s going to keep the house we’re renting because she’s doesn’t have a place to go or whatever. I’ve been living in my van with my two cats for the last day or two.” And he said, “Hey, I’m going on tour. Here’s the key to my apartment. It’s over here in Silverlake. Here’s the key; here’s the address. Stay as long as you want.” It was incredible! That was in the first week I knew him.

That’s a beautiful story.

Yeah, it is. When you think about the foundation and the musical instruments that they’re supplying to the New Jersey, New York area that Neal was from, all the work that he did to be a nice guy or a nice person, that that’s more than just, “Okay, now we should listen to his music because he was a rad dude.” No, he’s putting instruments in school music programs that I took for granted because I’m nearly sixty years old, and in the ’70s, everybody who wanted to play an instrument could play an instrument in school. We had nine different kinds of bands– jazz bands, marching band, orchestra, everything, and instruments were there– but it’s not like that anymore. They’ve cut so much funding to the arts in school. It’s not good, and the foundation is actually putting instruments in the hands of people.

If you read any articles or read any interviews with Neal or watched anything on YouTube, you saw how everything meant so much to him–his records and his first guitar, him making his first album and even making his last album, everything meant so much to him. The person I knew– if I handed him a new Frausdots record, or if I made a solo album or whatever, he was like a kid, “Oh, wow!” He was always excited. Always.

And the story he would tell me about finding his first Aerosmith 8-track in an abandoned car and getting this first guitar and all that stuff– it was like a world of wonder for him. And I think that’s probably what made it so easy for him to make the decision that he made. Not to get all heavy, but I just don’t think it was out of… A lot of people feel desperate and a lot of fear; they feel like there’s no way out. I don’t think it was like that with him. I just think it was just like, “I just got to get on to the next thing.”

If someone’s new to Neal’s music, where should they start with his catalog?

Wow, that’s a great question. It really is because some people come at it through the Grateful Dead community angle, which I don’t think is a good… I would visit No Wish to Reminisce, Anytime Tomorrow, Roots & Wings, and his first album Fade Away Diamond Time. They’re songwriting without any extra flash.

I was wondering if we could shift gears and talk about your label, Curation?

My favorite thing to talk about. I don’t have to sneak it in [laughs]!

Did you begin with a mission statement or inspiration from labels that you love?

Yeah. David Geffen, Asylum Records; Alan McGee, Creation Record; Bruce Pavitt and John Poneman, Sub Pop; and all labels that I’ve been on before–I saw them do it. Even though I might have made some mistakes on those labels, and they might have made some mistakes with their own labels, I saw that model when it was really really, really celebrating and supporting the artist at no expense. I don’t mean like money or expensive; I mean like putting the music first and then seeing what happens, because if everything is in the right place and your hearts in the right place and you’re surrounded with good people who make great music, then you really can’t lose. If you’ve watched the story of Asylum Records [Inventing David Geffen], David Geffen started the label basically, so he could put out Laura Nyro, and then she ended up going to another label. But then history, you know, he ended up putting out Jackson Browne, the Eagles, and a million other great records. Well not millions, but thousands of other great records.

Curation was something that my partners and I were talking about starting. They really believed in me. They watched me help artists over the last twenty years with no strings attached, as helping them get record deals or managers or booking agents, and they’ve gone on to some very big things, and they’re like, “Well, why don’t you make it formal?”

So I said, “Yeah, I don’t have any bands. Beachwood Sparks really isn’t together, but I might be able to ask the guys if they could do something, if we could reunite. GospelbeacH still had one more album on a contract with another label [Alive], so I thought of Neal Casal. I reached out to him and I told him I was starting a label called Curation Records, and we wanted him to be the first artist on it. He said, “CURATION TO THE WORLD!” in a text. Then I said, “Okay, well, I know you need some money. So where do I send it? Let’s do a deal. Let me sign you.”

So, I called his manager and talked for two hours. He said, “Neal’s getting his head around being a singer-songwriter again, but it’s time for a career renaissance.” That’s what they were calling it. But there was a hesitation in Gary [Waldman’s] voice. It wasn’t like he didn’t want to do it with me. It was like Gary must have known or suspected something because he was slow to the process.

History went on, and Neal left us. So the label was started, and we were off and running. Then the second band [Mapache] I wanted to sign while we were putting the company together, they took a deal with another label [Yep Roc] before I could even give them an offer. I thought, “This is a sign. This is a weird start to this label.” Then we started finding other bands. We started with Pacific Range, and once we had a little success with their album, we had some other artists start taking notice, and it was a lot easier for us to get people to return our emails and phone calls because we did so well with that album.

Curation is a family thing. I don’t want it to be identified with just me or just with one band. I want it to be like a vibe or a feel, something that is curated from our own kind of experiences and love. We have a guy from Nashville, Sean Thompson, coming out with a record. We have Jody Stephens and Luther [Russell] from Those Pretty Wrongs. We’re starting to branch out of L.A. a little bit besides the normal roster of GospelbeacH, Farmer Dave & The Wizards of the West, and George Is Lord.

The Triptides single is Curation’s latest release?

It’s actually shipping this week. It’s a 12” single, “So Many Days”, that’s proceeding their first album for Curation, which is also called So Many Days, and it’s so incredible. They’ve got some Georgia roots.

You also have the Uni Boys, who are about to open for the Black Crowes?

Talking about Curation, think about this: We had Beachwood Sparks as a band. We meet Neal, he becomes friends with me really quickly. He’s friends with the rest of the band. He opens for us. Next thing you know, we got asked to tour with the Black Crowes, and we needed more juice on stage, some extra singing, and some extra guitar and keyboards. We asked Neal. We didn’t have any money to pay him. He was used to touring on tour buses. But he came along with us. He went on that whole tour. So there’s that connection with the Black Crowes. Then 9/11 happened, and we take that picture for Magnet magazine, so Neal’s documented as a member of the band, but the only album he recorded with us was Tarnished Gold. He’s on every track, and that was just a wonderful experience.

So there’s Neal, there’s The Black Crowes and Beachwood Sparks, and then there’s the CRB [Chris Robinson Brotherhood] later, which revitalized everything to me. That gave Neal a true career renaissance. As a guitar player, it gave Chris Robinson the identity as like, ‘I’m coming from that Dead community without having to make the Black Crowes do it,” even though early on they were on the H.O.R.D. E. tour and playing with the Grateful Dead and doing Dead covers. Chris and Neal and the rest of the guys started their own community. They got in the van, and they played California up and down. I was living in Florida at the time. It was like, “Wow, Neal is doing this thing with Chris! This is cool!” And then they put all those records, and they built this really big Community. A lot these names on the Highway Butterfly album can be connected to the CRB.

It just so happens that Chris Robinson has been moved back to Southern California. He lives in Laurel Canyon. We’re still friends. and we still play music together and hang out, and I brought him to see the Curation band The Uni Boys. And now they’re going to open for the Black Crowes in Las Vegas at the House of Blues, the same place that Beachwood Sparks played with them twenty years ago. Almost to the day. Twenty years later! It’s pretty incredible. And Chris loves the band. I didn’t have to pull any strings to do this. This is a live rock ‘n’ roll band. We haven’t got them on tape perfectly yet, but they’re going blow minds when they get their record out. I think Neal would have been tickled pink over it. It’s weird as hell, you know, but it’s also really cool. It’s great for the label, it’s great for the band, and it’s great for The Black Crowes’ audience. They get to see a rock ‘n’ roll band– young twenty-two-years old– rock ‘n’ roll.

You can’t write this stuff. You know what I mean? Like, you really can’t! I don’t care that I’m not a famous musician, selling millions of records and rich all that shit because almost everything that I could dream of comes true. That’s why I keep Neal’s spirit alive. You have to navigate a lot of people wanting to bring negativity into the stuff. It’s not even Neal and suicide and depression and hardships in music, but just in life– it’s just really hard. You gotta keep it positive. You got to keep it real, but you got to keep it positive. Man, I swear to God, Neal and I would have these talks, like that thing with me and his apartment. I didn’t say, “Oh, man, I don’t have anywhere to live.” I just kind of said it, and he said, “Oh, man, that sounds rough,” and I go, “It’s not that bad.” He gave me a teasing, and that was it. We never talked about it again. It wasn’t like we were trying to be macho and didn’t want to talk about our feelings. It was just like the act itself said everything that needed to be said, like, “I’m here for you. And always going to be here for you.”

Neal left me one of his guitars, and I was playing it the other night, and I was thinking to myself knowing that this interview was coming up and Highway Butterfly was coming out, and the project really helped Curation and Neal’s back catalog, and the artists on Curation and Beachwood Sparks and GospelbeacH. It really helped in a weird way to promote the stuff, and that’s not a bad thing at all. It’s not why we’re doing this at all you, but the fact is that’s a gift that you get. I’m sitting there strumming the guitar, shaking my head, and I’m like, ‘God dang it, Neal. This isn’t the way that we wanted to do it.” When Gary Waldman saw the video that we made for “You Don’t See Me Crying,” he said, “Man, this is a really good video. This is gonna really do well.” But it’s not like a normal record where we can say…

“It’s burning up the charts!”

Exactly, exactly. But we still celebrated it. We still gave ourselves permission to praise Dave Schools and Jim Scott for what they did with the sound of this record. It’s not like, “This is in Neal’s honor.” It’s more like, they’re fucking great. Jim is an incredible producer. They kept the vibes and the sonics in line. I listen to it, and I say, “If this doesn’t win a GRAMMY, then screw the world because it should win.” And that has everything to do with their talent and their studio prowess. And that situation and vibe have a lot less to do with Neal’s suicide. I do like to celebrate the success of it, and I want it to be successful. Shoot, I order everything and pay for it. I want to order all the DVDs and hoodies and CDs and the five-record vinyl for my friends. I bought Neal’s book to support the foundation. I like to support my friends, anyway. I don’t like free records, even though I get a lot of free ones. I like to buy them, and I like to pay for tickets for shows. I think we’re allowed to celebrate the success of it.

Speaking of celebration, Curation reissued the first Beachwood Sparks record to commemorate its 20th anniversary. It’s a gorgeous package. Are you planning a similar anniversary release for Once We Were Trees?

No, there isn’t. It was sadly nixed by Sub Pop. I thought Curation would have been a good thing for that.

Damn, I was counting on that.

Well, Sub Pop is cool. That’s why I listed them as an influence because not only have they been cool to me about Beachwood Sparks and Frausdots, but they gave us permission to do the anniversary reissue of the first album, not just only because it was CD-only back then and Bomp did the vinyl, but it was more like they were cool with it.

There are plans– I hear– for a full reissue of all the records in one set because they are out of print. If I had more money, I’d make them an offer.

I wanted to talk about GospelbeacH a bit. I’ve been head over for those records. I’ve seen the roster shapeshift with each release. Is it more of a collective than a band?

It’s a collective, yeah. It’s not a solo project at all. But now it’s pretty much a partnership between Jonny Neimann and myself now, even though we have some people who have played in the band for the last year or two years– Matt Hill and a new drummer, and the people who have come and gone like Jason Soda, Ben Reddell, and Tom Sanford, and Trevor Beld Jimenez, who co-wrote a lot of the songs with me on Let It Burn, but it’s definitely a collective. I’m so glad that I didn’t name the band. Patrick from Alive Records kind of suggested the name, and it was kind of cool because it does describe a place, so it can be like more of a collective rather than like, “I Am GospelbeacH.” It’s like the beach is a place where you can go and have those places to hang out and get some sun.

What’s next for you guys? I loved the glam/bubble gum EP, Jam Jam. It’s hardly left my turntable.

There’s a new album. It’s almost finished. I’ve been really picky with the songwriting because Jam Jam was covers, and it was so great because I met Bob Glaub and Don Heffington, the guys who played the bass and drum. I met them through Neal. I’m a huge Jackson Browne fan, and Bob is his bass player and was on a lot of his records. Don has just recently passed away. He played with Bob Dylan, and he was in Lone Justice. They played on Jam Jam, and they loved the whole approach, and they loved the studio. We were going to make the GospelbeacH album with them, but Don sadly passed away, and that really hurt a lot. It was very quick and sudden, but at least I got to know Don. I met him at Neal’s memorial concert at the Capitol Theater. I asked him if he would want to play with a studio session, and him and Bob both said yeah. And it came out really good.

Gospelbeach is a full collective, and for the album that we’re making we’ve been enlisting other people. We’ve got some new faces and new voices, new guitar players coming down to play on it, and it’s just been slow going because I’m making it for Curation, so I’m really hard on it. I want it to be the best it can be. And that doesn’t mean that I’m fine-tuning it. It means that I think if a band came to me with this record, I’d be like, “Okay, it’s really good, but you need some more songs.”

I love going through your old interviews because you’re such an ambassador for sounds. You champion acts like REO Speedwagon, Jackson Browne, or Poco, bands that are maligned in certain circles. You love ’em, unflinchingly. I was wondering if you could recommend some similar bands. Pop culture latches onto something, like Big Lebowski and “I hate the fucking Eagles”. And , therefore, you have a whole generation of young people who just say, “I hate the fucking Eagles” without listening to the Eagles…

And they’ll never listen to the McGuinn-Clark-Hillman or Southern-Hillman-Furay. Or the Chris Hillman solo records like Slippin Away and Clear Sailin’. There’s so many, my God! I’m on the spot right now. Black Rose by J.D. Southern is one of my favorite records. I loved all the Linda Ronstadt records. These are mostly on Asylum. The Asylum catalog from ‘74 to ‘81 is full of everything that a person like me needs. It’s from the most obscure to the most popular, to the Linda Ronstadt records produced by Peter Asher, you know what I mean, like, going all the way up to Mad Love, which was supposed to be her punk or new wave albums with the Elvis Costello and Dave Edmunds and the guy from The Cretones, the guitar player who wrote some songs for her and played on the album. But it’s still produced by Peter Asher, and there’s still a kick-ass Neil Young cover on it. That kind of west coast studio craft was what we brought into Let It Burn. That’s what I’m trying to get away from now because chasing that sound is like chasing your tail.

Given that it’s Thanksgiving next week, I wanted to close by asking you what you’re thankful for these days.

I’m really thankful that I have this opportunity, and I’m healthy, and I’m happy, and I’m able to help people around me. I’m just thankful that I’m in a position to help people, and I’m not stretching myself too thin, and I’m not sacrificing much to do it. I wrote a line in a Beachwood Sparks’ song [“Banjo Press Conference”]: “I want to help him/ but I can’t help myself.” In the past, I really wasn’t in the position to help people spiritually, financially, and maybe I could musically because I knew people, but now I’m actually in a position that it feels right to help people, and I’m really thankful for that because it means that I have good people around me who are supporting me. And my wife and I are back together. We had separated for a year, and we’re together.

I’m thankful that I’m not depressed. I used to be very depressed. That’s why it’s so easy for me to talk about Neal’s suicide because I’m a survivor of that, and I’m also a survivor of addiction. I know it’s harder for other people. It’s a very difficult subject. But since I’ve just been through the wringer, it’s easier for me to talk about, but I’m thankful that I’m here to talk about it.

And I really appreciate it, man. It’s so cool to talk to you, Charlie, because I had no idea I was going to talk about…The interviewers just don’t know anything about GospelbeacH or Beachwood Sparks. We’re one of the lesser-known bands on the comp in some circles, but that’s what makes Neal so special. Everybody from Bob Weir to Farmer Dave, you know what I mean? The whole spectrum is covered. There’s something for everybody, man. I hope they enjoy the compilation.