In his double chapbook Standing on the Verge & Maggot Brain, his poetic tribute to all things Funkadelic, Adrian Matejka writes, “Funk is/ always on the one, full of thumping/tongues & low-down uncertainty.” This juxtaposition of good-time rhythms and unease is at the heart of classic funk records, albums trafficking in intensity. Explorations of matters of the heart and cultural unrest are soundtracked by tough rhythms and flamboyant instrumentation. Funk legends like Parliament, Funkadelic, Shuggie Otis, and Baby Huey– whose work manages to sound both earthen and astral– comprise the genre’s golden age, leaving contemporary crate diggers searching for likeminded artists. Boutique labels like Numero Group and Light in the Attic work miracles with their reissue campaigns, releasing long-neglected funk obscuros. Given the affection for these releases, one might think the genre has become the stuff of reminiscences and collectors.

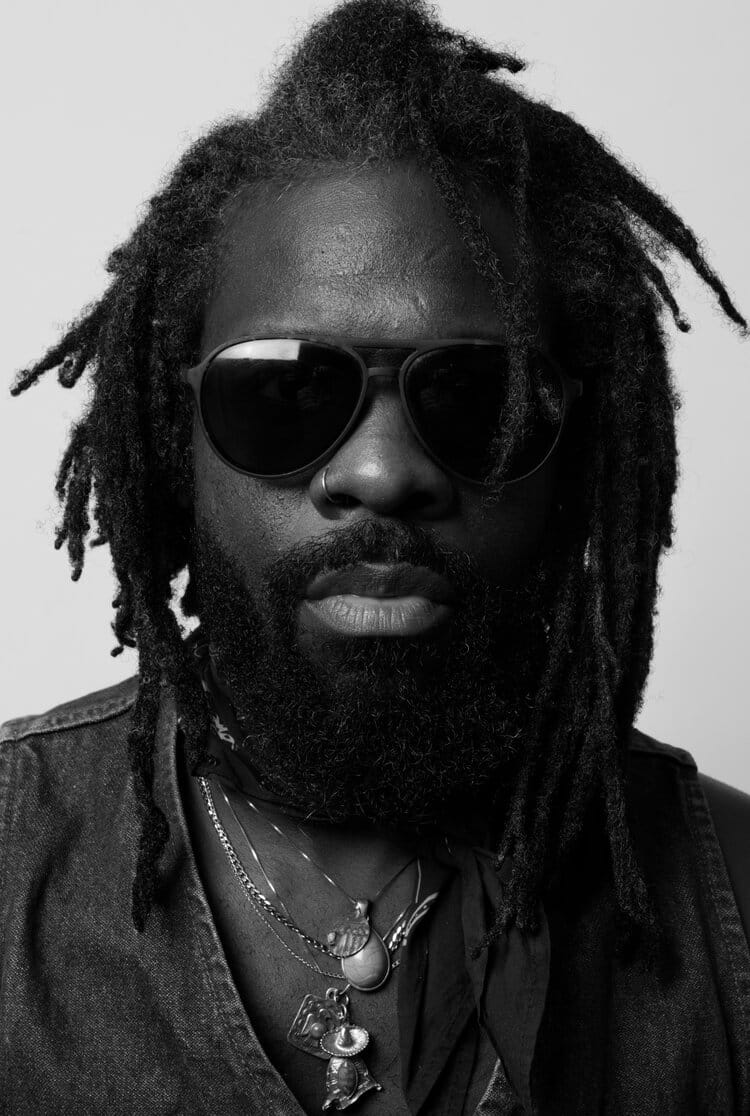

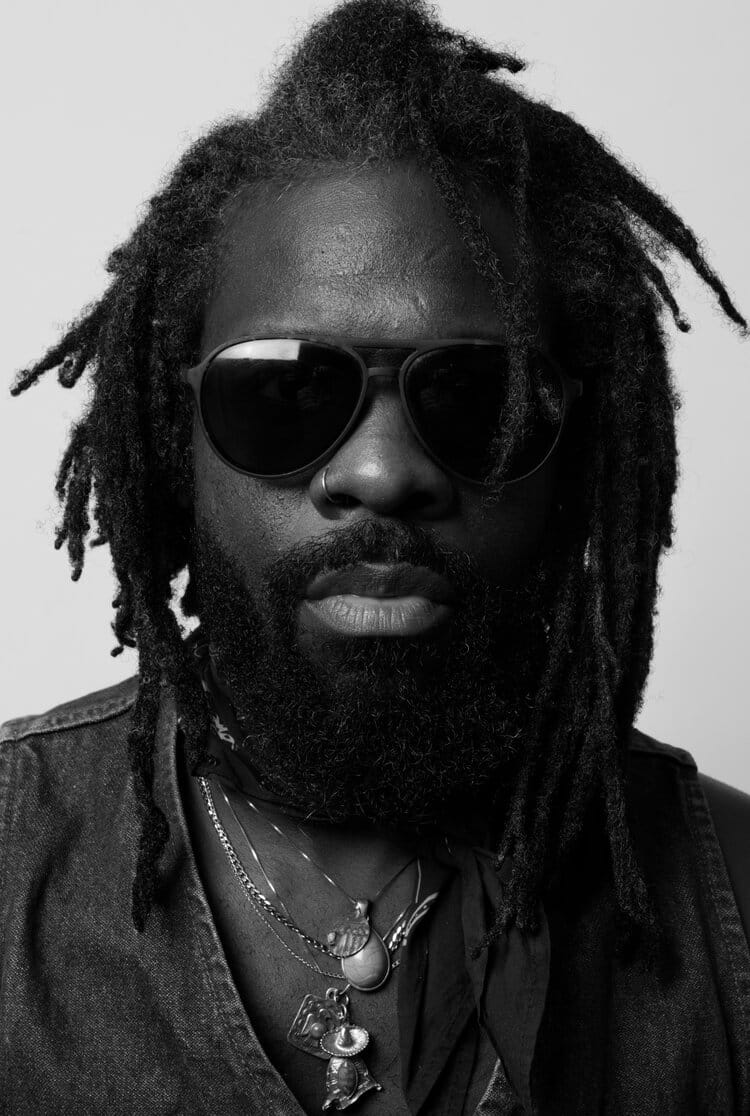

Enter Boulevards, whose latest record, Electric Cowboy: Born In Carolina Mud settles into the groove laid down long ago by funk’s standard-bearers. A career reset, EC finds Boulevards– né Jamil Rashad– abandoning the electro synth-funk of earlier releases for the raw and elemental. As a prodigal son, Boulevards sees the record as a tribute to his North Carolina roots, the mud of his childhood. With the support of a new label, Normaltown Records, an imprint of New West Records, Boulevards finally had the budget and support, giving him the chance to play the role of alchemist, turning the studio into a laboratory. Everything about EC howls that Boulevards is all in– the gonzo cover art, the sculpted, three-dimensional production, the glittering instrumentation, the cinematic sequencing, all suggesting this is his canon contribution to a funk lineage starred with masterpieces like Shuggie Otis’s Inspiration Information, Isaac Hayes’s Shaft, and The Baby Huey Story. Electric Cowboy is heavy– thick orchestration, weighty subject matter– compelling, essential, and like its creator, shouldn’t be ignored.

Boulevards lands in Macon, GA for a FREE performance at the Hargray Capitol Theatre on Friday, March 11th!

CF- Your sound has continued to evolve from each album to the next. There’s the electro-funk of your earlier records, and with your most recent EP, Brother, and now Electric Cowboy, you’re embracing a simpler, roots-ier sound. You don’t seem content to hang on to one sound for too long. How do you account for your progression?

B- A lot of it came from growing up listening to different funk, soul, and jazz records. My dad worked in radio for close to thirty years at Shaw University. They had a radio station, 88.9 WSHA. He was always giving me records, giving my sister records, putting me on and always telling me that to be the best, or if you want to be great at this, then you got to listen to different sounds, whether it was blues, whether it was funk, whether it was soul or ’80s or New Wave or reggae and obviously hip-hop. I wanted to incorporate the sounds that I love, the things that I enjoy listening to and enjoy grooving to. At the same time, I was still figuring out my approach to funk music and to modern funk. I was checking out a lot of the artists that tried that approach. You have the Thundercats and Dâm-Funks of the world, all these different artists. I was trying to figure out what the approach was because there’s a lot of soul artists and soul revival, but there’s not really people doing funk. And if they are doing funk, it’s really a jammy band, like Dumpstaphunk– they’re cool people– and Galactic, but there’s nobody doing it in a cool, modern way that has a little bit of the appeal of how they were doing it back in the day. A lot of the artists that do it sound really cover-ish.

At the time when I was doing the Groove record, I was really heavy into electro-funk– I’m still always going to love that type of stuff. I was really digging that dancey, disco-y type of stuff that usually wasn’t heavy, subject-based; it was about the groove, the bass, very, very catchy hooks, and then the lyrics. That’s what I was doing at the time, and then I got more in the synth phase, and I was dabbling into that with the Hurtown record—more synthesized bass and at the same time darker notes. And then, of course, when I was living in LA, I was going to Echo Park and the Funky Sole dance parties. They were always playing these really dirty, dusty, rare grooves, and I’ve always loved that; I just didn’t know how to do it. When I was in LA, I was working with Russell Manning, my producer at the time, and we were able to still keep it bedroomy garage-funk that’s very lo-fi, and that’s something I’ve always loved too, like how James Brown did– that really basic drum kit, with really basic guitars and drums, and a little bit of organ. And I still love that type of stuff, man. I love that type of stuff.

Then we got to this record, this being my first studio record, I was indie, then went New West, and when I had those other records, I really didn’t have a lot of money, so it does help to have a label that believes in your vision and that’s able to give you a little bit more to work with, right? I chose Adrian Quesada from Black Pumas; I chose Blake Rhein from Durand Jones and Colin Croom [from Twin Peaks] because these guys have a good feel of soul and funk, and they could be able to help me get across what I want to do. I feel like nobody’s doing what I’m doing right now. Like I said, you still have a lot of soul artists, and that’s cool, but nobody is still doing that old school, really raw, grinding funk that still has appeal, that still has some pop sensibilities in that appeal– and that’s what Boulevards is. I’ve always tried to have that approach. It was just having the right producers at the right time. I had to make these other records to get to this point. Some careers are reversed– they make their great records, continue a specific away, and they fall off. For me, I just had to keep learning and learning and learning and learning and make those records and get to this point.

What’s the collaborative process like for you, being a solo artist and then working with new people?

I’m a solo artist, still. When it comes to recording records and writing records, that’s different from touring with Boulevards. Touring is like I hire guys that I like to tour with and like being around and collectively can also play together. I try to keep it different because I don’t like too many hands in the kitchen. As for the guys I tour with, I don’t want them to be involved in the writing process. I know what Boulevards wants to do. Nobody knows the vision as strong as I do.

For this record particularly, I reached out to Blake on Instagram; I just slid into his DMs. I’m a music nerd, so I was always reading liner notes. Blake wrote for Numero [Group, the reissue label] and obviously Colin with Twin Peaks, and Adrian Quesada did a lot of really funkier, heavier stuff before he was with Black Pumas, and I liked that stuff better– not saying that Black Pumas stuff isn’t good; I just feel like his side project has more character, and it’s more him, whereas in Black Pumas, he’s making a product, right? For me, it was like, “How can I approach this?” I hit him up, and I told him that I had a playlist of music that I loved. I said, “Look, man, I want to be the face of modern funk. You already have Durand Jones; you have Black Pumas. I want you guys to be able to help me bring the vision and bring all these other past records that I had before together and still make this Boulevards, but show evolution and show growth.”

Blake was sending me skeletons through my iPhone email, ideas that we were working on. Basically, I would write these melodies, write these lyrics, and send it to him through my iPhone. He would say “yay” or “nay” or tell me certain things to work on. After we had these demos and skeletons, I went up to Chicago to meet, and that’s how we started the record. That’s how we basically recorded everything, with the background singers, the strings, and all that stuff, and all the different players– we did everything fresh. Blake and Colin would send these skeletons of just raw, raw instrumentation and ideas, and I’d write over them. Months later, we would record everything again, so things ended up sounding a little bit differently.

How do you distinguish between a collaborator– someone you want to work with– and a friend who has a rad record collection?

The thing is, I didn’t really know Blake like that. At the same time, Blake is a music nerd like me because obviously he’s a Durand Jones guy, and he works at Numero Group– if you know Numero Group, you know that they put out the best reissues. I kept stressing: This is a Boulevards record; it’s not a Blake record. The goal is that you guys are producers, right? That’s why I always say this is my first record– it was very close-knit and very surgical. You had people in there doing what a producer is supposed to be– bring the best out of an artist, bring the best sensibilities out of an artist, highlight the sensibilities of an artist and help that come across and translate into a record. I feel like they did that really well.

When we were in the studio, I kept stressing, “This is a Boulevards record. I know what you guys do in your own band.” At the same time, I wanted to have a little bit more freedom and fun with this record because like I said, they’re in established bands that have a particular sound, and I’m not there with those bands, yet. So for me, it’s like, “We could still have a little bit of fun and be funky.” I wanted those guys to have fun making this record and be able to experiment and express themselves, whereas, in their bands, they’ve probably got so many hands in the kitchen, saying, “We gotta do this. Or we gotta be more mellow.” I just wanna keep it funky like George Clinton, Shuggie Otis, all those guys back in the day, how they were able to express themselves, no boundaries in the funk– that’s how they were able to have fun. You could tell they were having fun on those records, whether they were getting high and trippy or whatever, like they were having fun enjoying those records. There was a new kind of soul, and that was the thing that’s really cool to me about listening to Shuggie Otis or George back in the day. Where all these other cats were doing the regular soul, they had a different approach that distinguished themselves different from all the other cats. Even Betty Davis…

Rest in peace…

Yeah, I mean she wasn’t doing your regular soul singer. She had a different approach to soul. She kept it funky and really, really raw. And that’s what distinguishes her from the Aretha Franklins or the Gladys Knights of the world. She was different, man. She was more raw. And even though she really probably didn’t commercially succeed, people respected her ambition. She got a lot of respect.

You recorded Electric Cowboy in a few different places– Chicago, Nashville, and Atlanta. How were you able to maintain a cohesive sound?

It’s different pieces, right? The whole thing with Chicago, that was the nuts and bolts. Then you had the background singers, Ashley [Wilcoxson] and Leisa [Hans], that sing on the Black Keys records and a lot of Easy Eye Sound– they’re in Nashville. And Nikki [Lane] as well. You had COVID at the time, so we had to do what was best. Ultimately, I would like everybody to be in the space together, but we’re all professionals. We sent emails; we sent detailed notes about what we wanted to do, and they were able to get everything across that we wanted to do with them not in the room, just talking by phone, by email, by Instagram. They were able to get the job done.

You mentioned Numero Group and liner notes. Are you a record collector?

Yeah, what do you want to talk about? (Laughs)

You laugh, but it’s something I always ask, try to find my likeminded folks. I’m shocked, though, because a lot of artists answer “no.” They’re fans but not fans…

Oh, yeah. I get that from my daddy, from him being a radio DJ. That’s just a given. And now, of course, you have electronic digging. It’s something that’s always been with me, being able to go out and find records– or going on Spotify, Discogs, or Apple, or really digging deep into certain playlists and finding stuff that I like.

Any folks besides your dad who kept you in the know, music-wise?

Just my dad, really. That’s what happens when you have a dad that works in radio, who goes there every day. I had friends in high school, kids always being into different punk bands, always dabbling in different scenes, but usually, it was my dad and myself. I was always curious to know what was out there. I’m all about keeping it funky, and if it’s dope, it’s dope. If it sounds like shit, I’m not going to listen to it. If I can connect with it, I’m going to listen to it.

For me, I connect with a lot funk and a lot of punk music and punk music more than anything. That’s not saying I exclude indie music, because there’s a lot of indie music that I think is great. And there’s still some Top 40 music– I went through a whole crazy Top 40 phase because there’s some of that stuff that I like to do as well. And obviously, I love hip hop. Nas’s I Am.. is the first CD I ever bought as a kid when my dad took me to a record store– and I bought it with my own money. I have hip hop roots, and I used to like rap. I rapped on those first few records that I did. I rap every now and then…

Can you talk about your punk background?

When I was living in Charlotte, I was into the hardcore scene and going back to Raleigh, there was the hardcore punk scene. The thing that I love about… I know a lot of people don’t like this music, “It’s too aggressive; there’s screaming,” but I say, “If you ever go to a show, they shows are rowdy; it’s beautiful.” The frontman showmanship is amazing, and I was always drawn to the frontman showmanship of them being very charismatic and just not giving a fuck. I just loved that. To me, that was one of the things that drew me to it. And obviously, a lot of it, if you actually sit down and listen, a lot of those punk songs and hardcore songs, the lyrics are just so dope. Obviously, a lot of it you miss because of the screaming (laughs)! But musicianship too, with the double pedal drums, the bass, the guitar playing, I’ve always been fascinated by it, man. Guys playing that fast, that hard, that heavy, it was just amazing to me, man. I can’t really describe it; I was always drawn to it. I keep telling myself, “I haven’t been to a hardcore show, a punk show in forever. I need to go.” I’ve been craving one. Hopefully, I get some time, and hopefully COVID stuff gets better and I can go out to go ahead and do one!

Punk is one of those genres, like metal, where allegiance is everything. Did you feel pressure to ride with the scene, or was it easy to eventually branch out, do your own thing?

There was always pressure with guys I was in certain bands with, but you know how it is when guys are young– you’re figuring it out as you go; you’re partying and drinking; you got girlfriends; you’re serious, you’re not serious. I was always serious about music. People don’t know this, man, but I used to produce. I used to make beats. That was the thing I wanted to do before I even got into music. I didn’t want to be the face of anything. I wanted to be behind the scenes. I wanted to write songs and write beats– that was my thing. When I was doing those punk bands, I was writing beats, but then something came over me. It was like, “I gotta go solo.” That’s when I started getting focused on songwriting and getting focused on listening to a lot of pop music, really listening to different types of music, locking myself in a room for ten-to-twelve hours a day, studying music, music, music, and studying, my approach of writing, writing, writing, thinking how I was going to make my own unique style that differentiates from everybody else. And then it took me some years and years and years. I’m still figuring things out, but I’m pretty close, so I mean, there was always pressure, but I’m always going to do my thing.

I’ve always compared punk music to funk music. Back in the day, that to me was rebellious, what the black younger kids were listening to before hip hop, you know what I’m saying? It was a lot of the funk, like Funkadelic, Brothers Johnson, Shuggie, Baby Huey, all the Curtis Mayfields. That music was very conscious or very rebellious before punk music and hip hop really came. That’s what started it all. That’s what I identify with, man. I love it.

I wanted to talk about the lyrics for Electric Cowboy. It doesn’t sound like it’s a COVID record, which is refreshing…

It’s definitely not a COVID record. That’s for damn sure.

But it still sounds heavy. Those funk guys sometimes responded to politics and the current events of their day. Did you feel the need to do the same?

Hell no! I’ve always been a strong believer that you should always write about stuff that you’ve seen, things that you been affected by as far as in your friendships, family, and the circle that you feel connected to, and also things that you’re going through. So for me, the first couple of records were still things that I was going through, but it was very, very light, very, very fun. I think also too there was a little lack of focus because I was heavy in my addiction and drinking and all that stuff. I think once I got sober and once I became clear-headed and focused, I was really able to dig down inside myself to be able to write lyrics that are more relative to me. I wanted to write songs that I knew that if nobody else was going to fuck with them, I could fuck with them– I can connect with them, and I can listen to them. I’ve always had the approach of me talking to myself, so a lot of this record is me talking to myself, or the angel or the little whisper on the left side or right side talking to me. But there’s writing about the experiences I’ve been through in my journey with addiction or things I’ve seen as a black man. I’ve seen certain men or women that are connected to me go through things as well, and writing from their eyes or writing from what I’ve seen because obviously, sometimes when you have friends and family, they go through things that affect you as well. I had to put some of that stuff into songs and arrangements. Blake and Colin were able to assist me with that and help me keep as much of that as possible.

Once you got sober, was there a fear that you wouldn’t be as creative as you were when you weren’t sober?

Yeah, I think as far as when I got sober, I was definitely nervous, like “Damn, how am I going to be able to approach this? Is it going to make me better? Am I going to become more wack?” (Laughs) “What will people think listening to these records now compared to my old ones?” For me, I really don’t care. I’m more focused, and I feel like these records, these songs are a lot more focused and better developed than they have before. That’s not discounting everything I’ve done in the past. I always feel that every artist has a journey– sometimes you have to learn from making records and being creative and, obviously, going through certain experiences in life. I feel like going through those different experiences with those records, getting dropped from a label, and the fact of what I’m doing now, I think if I wouldn’t have been able to make those records, I wouldn’t have made Electric Cowboy. This is my journey; this is what I had to go through to make this record.

How much of a concern was sequencing? For me, the album takes a dark turn once it hits “Ain’t Right” and “Modern Man”. Those synth lines sound like something from John Carpenter…

Dude, man, I’ve always told myself– you can take it the way you want– I feel like I’m the king of sequencing, man. When labels ask me, I’m like, “I got this. Let me do this.” Because nobody knows the journey and the vision like the artist. Nobody does. Friends or bandmates, they might think they do, but they don’t know the vision and they story that you’re trying to tell.

That’s another thing that happened with this Boulevards record– things became more cinematic. That comes from me loving Blaxploitation films and western movies as a kid. That’s what I told Blake and Adrian– listen to Super Fly, go listen to a lot of those exploitation films and music and see how they flew together. That’s how I want people to feel when they listen to this record, look at the liner notes, and put it on their headphones or whatever speakers they’re listening through. I want them to get the feel, as far as taking them through a journey, through Jamil’s Carolina mud. As cliché as it sounds, I want them to be able take that journey. I obviously had those different things like the strings and the organs, the way we compose the different placements for different guitars and melodies, I wanted it to have that cinematic feel.

When it comes to “Turn”, it’s the start off. It’s talking about when I was younger. It gives you an intro about when I was a kid– I never smiled. I was always mad all the fucking time. My dad used to tell me, “The world’s gonna keep turning, no matter what happens. If a girl leaves you or people turn on the you, things are going to keep going.” I end the record with “Problems”, and that brings all the songs together. Once the listener hits “Problems,” that brings everything together, all these issues, all these problems. Even the composition– it’s a good time to send everything out, man. It’s like the credits roll through. You feel that organ coming in, those guitars, those strings wailing. It’s the emotion of tears that’s on the track. It’s the new established Boulevards sound– being known for being more cinematic and painting a picture with these instrumentations, not just with the lyrics, but to be able to create pictures and create stories through instrumentation. Isaac Hayes was great at that; Curtis Mayfield was great at that; Shuggie was great at that. They were great, outside of the lyrics, with the instrumentation being able to paint a picture of the ghetto, where they were from, the inner-city life. I wanted to paint a picture of my life in North Carolina, my journey.

Would you call this your tribute to North Carolina?

I feel like it’s a start to what’s to come with the next couple of records. I feel like it’s definitely a nod to North Carolina, for sure, because this is where I was born and raised. Without me being born here, there’s no Carolina Mud.

Does Electric Cowboy feel like a career reset for you?

Oh, yeah, man! I definitely feel like it’s a reset. I wish it wasn’t, but every artist has their journey. I had to make those records to get to this point. This is the starter, my first studio record. Everything else was done in a bedroom, a garage, with not much money at all to get the vision or point across. With this, I was able to get the vision across the way I wanted to do it, and I really feel good about it.

I think a lot of us grow up dreaming of making it in New York or Los Angeles. But what have you gotten from growing up in North Carolina that you couldn’t have gotten anywhere else? Is there an underdog vibe you can relate to?

There’s definitely an underdog vibe. I’ve always considered myself an underdog, especially with music because all the big bands are from either Atlanta, Austin, Nashville, New York, or LA, whereas artists, not just including myself, in Raleigh get overlooked because we’re in the middle of Miami, Atlanta, Nashville, DC, and New York. There’s still great artists out here that obviously [get attention]. You’ve got Jay Cole, American Aquarium, Sylvan Essos, Hiss Golden Messenger— those guys are doing it, but there’s still so much more in North Carolina that people still haven’t heard. I think a lot of writers, journalists, and fans tend to overlook North Carolina unless it’s country, indie rock, or hip hop– because there’s a lot more shit in Raleigh, North Carolina, that people don’t know about. You get sick and tired of that happening all the time. There are so many other great artists here.

Who are some other North Carolina artists who deserve a shout out?.

Lonnie Walker, Kooley High, Zack Mexico– they tour with the band Future Islands, who is North Carolina-based, as well– Kate Rhudy. There’s band called ZOOCRÜ that’s really dope.

Electric Cowboy is a headphone masterpiece, with its attention to detail and instrumentation. It’s a complete package. What are some albums that you consider headphone masterpieces?

I would say, obviously Curtis Mayfield’s Super Fly, Parliament and Funkadelic, Maggot Brain, and the Funkadelic record, Shuggie Otis’s Inspiration Information, the classic Isaac Hayes Shaft soundtrack.

I don’t listen to a lot of indie stuff, man, but I think the only real records that have been released in like the last couple of years that I feel are masterpieces are those SAULT records. Michael Kiwanuka is in there, Cleo Sol, all these different folks. Nobody knows who the musicians are. They keep their stuff secret– it’s all about the music. All their stuff to me is a masterpiece.

Also, Rick James’s Street Songs– masterpiece! That Country Funk, Volume III from Light in the Attic, Look Out For #1 by the Brothers Johnson; obviously, Al Green Gets Next to You; Marvin Gaye’s I Want You, you know is a masterpiece! I mean, the list goes on…

I’m so funny, man, because I’ve always told my friends in secret, “[Electric Cowboy] is a fucking funk masterpiece, yo!” (Laughs) I’m a music nerd, so I listen to a lot of music. I’m very competitive– that comes from me running track and cross-country, being in sports– so I’m very competitive, always listening to what’s out there, and literally, there’s nobody out there doing what I’m doing.