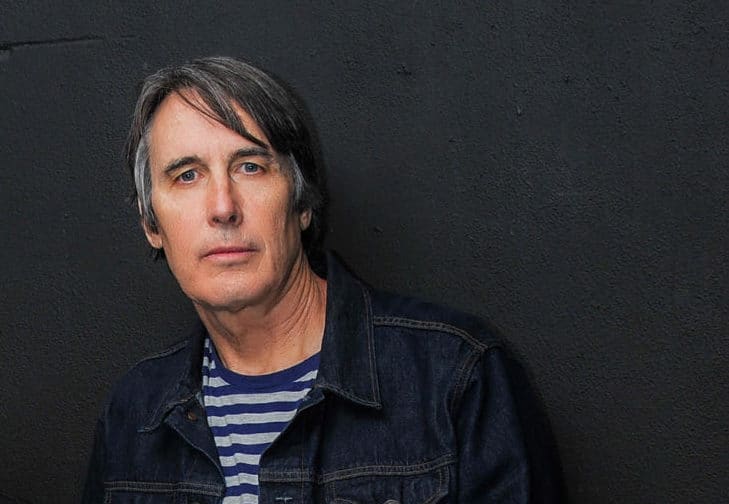

Americana Railroad is bookended with performances by Stephen McCarthy and Carla Olson, including the lead track “Here Comes that Train Again”, originally performed by McCarthy’s The Long Ryders, and the finale, a biting version of Gene Clark’s “I Remember the Railroad”. McCarthy and Olson’s presence on a record that doubles as a celebration of Americana music seems only appropriate. Scene royalty in her right, Olson starred alongside Gene Clark on what many people consider the first realized Americana record, 1987’s So Rebellious a Lover. Since then, she has staked her claim as the genre’s first lady. In 2020, she released her Have Harmony, Will Travel 2, another cherished record of duets with the likes of Terry Reid and Peter Noone. Stephen McCarthy, another roots pioneer, also makes an appearance on “Timber (I’m Falling in Love)”.

McCarthy’s resume is dizzying. He was a founding member of The Long Ryders, one of the first– if not the first– bands to meld punk and country western influences. Their debut, 1984’s Native Sons, provided a template for bands who sought to find the (in hindsight, obvious) 3-chord common ground between outlaw country and their downstroke 8th-note counterparts. Subsequent albums State of Our Union (1985) and Two-Fisted Tales (1987), were instantly sainted by those in the know. McCarthy also served as a part-timer of The Jayhawks, contributing to the band’s heartbreaking Rainy Day Music (2003). These days, he’s again playing with The Long Ryders, who released Psychedelic Country Soul in 2019, and is a recurring member of newly reinvigorated Dream Syndicate, who alongside The Long Ryders, were driving forces of Los Angeles’ Paisley Underground, one of America’s most important contributions to contemporary music.

In anticipation of Americana Railroad’s June 17th release, I spoke with McCarthy about his love of The Byrds and Gene Clark, the essentialness of travel, jamming with The Dream Syndicate, and his upcoming record with Carla Olson.

CF- How did you get involved with Americana Railroad?

SM- Carla Olson and I have been friends for a long time. She had me play on few records that she was involved with. When she made a record with Gene Clark, So Rebellious A Lover, back in 1987, and I came in and played some guitar, maybe some dobro– it’s been so long! We got to Gene Clark a little bit through my band The Long Ryders. He came and sang harmony on a song on one of our albums around the same time. Back in those days, you still had a lot of the bands that came before us still around making records. The people were still available, maybe you could meet with them or maybe get them on a session. Carla had a band called The Textones, and we were sort of on the same circuit. We would cross paths. I got to meet her husband Saul [Davis]. They were great friends.

I know that Gene Clark was the impetus for this compilation. What was your first exposure to Gene– did you recognize him as one of The Byrds or was his solo work your introduction to him?

The Byrds, obviously, were huge. I was pretty young when they were first getting going, but I was aware of the music just from the radio hits. My oldest brother, who was 11 years older than me, was totally into soul music. He would see Aretha Franklin or Otis Redding, or he’d see James Brown when they were in town. My next older brother was totally into The Beach Boys and Jan and Dean. He was only into surf music, so it was completely the opposite from the other brother. Then my sister was into pop music, British Invasion. She saw The Beatles play at Shea Stadium. I, actually, was in the car when we dropped her off. That piqued my interest in that.

But I really latched onto rock ‘n’ roll and country music coming together, and that mix was intoxicating for me. I came to know The Byrds a little bit, and to be honest, the first Byrds record that I had was one that came later, Farther Along. That was the first one I actually went out and purchased when it first came out. I loved the Gene Parsons stuff– at that point, the lineup had shifted, different guys, [Chris] Hillman had left. I loved the pedal steel and the banjo, and then going back and getting the other records with Clarence White.

But Gene [Clark], getting back to your point, he was a great singer, a great songwriter. He was a good-looking frontman. I was drawn to him, his style, and his poetry. And then later with his Dillard & Clark records, I loved that material. And a couple of his solo albums are just fantastic. I think that he’s really underappreciated, so later getting a chance to work with him was a real thrill. I’m always grateful to Carla for getting me on his records.

Of those ’60s standard-bearers, with The Beatles, The Beach Boys, The Stones, and The Who, did The Byrds stick out as your favorite?

Not initially. I think like most people, The Beatles were like scorched earth. They came over, and it seemed like there was nothing else to even match up to them. The Stones after that. And then, you know, just a little bit later, The Byrds’ singles, but then at this point, the late ’60s, I’m only 10, 11 years old, but you’re getting interested in records, and you go up to the record shop that’s half a mile away. You have a few bucks to buy a couple of singles. I was really getting into the Lovin’ Spoonful and The Band, groups like that. I might spend my money from cutting grass on a couple of singles, getting into that. I had a neighbor who played banjo, and that sound was fascinating to me. Being from Virginia, there are a lot of great bluegrass groups from here, like Ralph Stanley, and The Carter family lived here, and Jimmie Rodgers and Patsy Cline. There’s a great tradition of country music from this state. As you get a little bit older, you start to realize, “Wow, just in my backyard, there was this tremendous stuff that was going on.”

Were there any local artists that you admired, who might not have made an impact nationwide?

There was a country singer by the name of Mel Street. The guy took his life, which is very, very unfortunate. He was tremendous. He was around sort of late ’60s through maybe the late ’70s. George Jones was a huge fan of his. He was straight country. With the internet and all that, people are becoming aware of him.

You and Carla are bookended on Americana Railroad. The album opens with a new version of your song from The Long Ryders, “Here Comes that Train Again” and closes with Gene Clark’s “I Remember The Railroad”. How did you come to choose those two songs?

I wasn’t really involved in the decision-making on either. Saul and Carla, to an extent, had asked about that song. I think that they had this record in mind for a couple of years. Saul asked me, “Hey, what about that old Long Ryders song?” That wouldn’t have been my first pick– I’m not saying I don’t like the song. That’s my longtime band. I love the guys in the band and it’s a fun, cool song– but I never ever thought about resurrecting that. But they wanted to do it; they thought it would really fit the mood of the album. I said, “Let’s do it, but let’s put a different arrangement on it.” So it’s quite different than the other version. It’s definitely a new spin on it because to me, it wouldn’t really make sense to do it exactly like the Long Ryders did. As for the Gene Clark song. I think either Carla or Saul brought that in. In fact, I wasn’t familiar with “I Remember The Railroad”. I didn’t remember the song, to be honest with you, but they suggested it. I’m like, “Yeah, this is a cool song. Let’s do it, put some harmony on it.”

And “Here Comes that Train Again” isn’t The Long Ryders’ only train song? There’s also “You Just Can’t Ride The Boxcars Anymore”…

Yeah, good memory. That was one of [Tom Steven’s] songs. It seems like if you’re in a band that’s doing any kind of country-related, country rock or country-punk or rock ‘n’ roll-country– however you want to describe it– that’s a theme that definitely pops up. This record Carla and I are doing, I’m sure there’ll be some railroad stuff that pops in there.

Why is it important to commemorate the railroad and its place in America’s history? On the heels of that question, do you think there’s something inherently political or democratic about the railroads that appeals to you?

I think that with the founding of this country and as we expanded West, the railroad gave people some freedom to move about and discover new parts of the country. Of course, there’s a lot of baggage involved in that too. But yes, there’s a sense of freedom and exploration, going places unknown, discovering the country. You can get there, and you don’t have to be behind a wheel of a car. You’re free to think and write, whatever you want to do on the train. It really just opens up your mind to a new way of thinking about America and how you plan to get from point A to point B. I hadn’t put a whole lot of thought into that, but there’s just a great mystery and a great wonderment about the railroad, especially the steam engines.

Frequently, in my mind, at least, you’ve written songs, quite a few, about the downtrodden, whether it’s “I Had A Dream”, “Man of Misery”, or “For the Rest of My Days”. It seems like The Long Ryders addressed some of these concerns on State of Our Union, with Ronald Reagan in the periphery. Are class and wealth disparity issues that are still close to your heart?

Oh, absolutely. I think that the average Joe usually gets passed by. There’s a lot of wealth in this country, and there’s an awful lot of poverty. We were trying to– and this is a word that could be bandied about in different directions– we thought about some populist themes, trying to think about the Everyman, the guy who is struggling to survive in a modern world. So yeah, we thought about that in the old days. It’s funny how there’s a lot of revisionist history these days. Maybe it’s because politics is such a blood sport, nowadays, but I guess it always has been. When Teddy Roosevelt was running, it was pretty brutal.

But yeah, in the Reagan years, you can probably tell where my politics lie. I’ve always felt that the common, the average guy, average woman usually gets passed over in favor of people who are born to wealth, whatever, so yeah, those were common themes in our music and what we listened to Woody Guthrie, early Dylan, The Weavers, Pete Seeger, or whoever it might be. They wrote quite a bit about that.

The word populism has devolved over the years and come to mean something completely different. There was a for-the-people connotation, as you were referring to. Now it’s used to justify or rile up complete distrust in facts and reality. Now, QAnon is considered populism in action…

Right, nowadays. It does seem like it’s taken on more of a label of nationalism and the right-wing seems to have glommed onto that. They want to close the ranks and have more of a xenophobic kind of attitude towards other places and other countries. I think that this country, we’re nothing if we’re not all immigrants. I have two grandmothers that came in through Ellis Island, and I knew one of them quite well. They were from Europe. My mother’s mother, I knew to the day she died. I was about 35 years old, so I knew her quite well. And my other grandmother came from Ireland, so I’m proud of that history. I’ve gone back and visited both towns where they grew up and cousins and relatives. I’ve embraced that cultural diversity in the country. I think that we should celebrate that, and that’s what makes us all better. I think if more people were able to travel, to get around the world, it would be a better place. They would see how other cultures live and celebrate that as opposed to saying, “We’re closing on our border. We’re not letting you in.”

That’s a perfect segue way to my next question. We’ve talked about railroads giving Americans the chance to explore their country. Has travel been an important part of your life? Was it something you were able to do as a kid, or did that come when you began playing in bands? Is it something that’s essential for your creative process?

No, I’m from a middle-class family, so a big trip for us would be to go to the Outer Banks and set up a canvas tent (laughs)! In 1980, I backpacked across Europe with my best friend and had a 3-month Eurail pass for like $230 or something crazy like that, so we could just go wherever we wanted. This was in the fall of ’80, so it was leading up to the Reagan-Carter election. The people in Europe that we talked to were worried about Carter losing. We were like, “Don’t t worry about it. Not a problem. It’s going to work out.” (Laughs) You see how wrong I was? But yeah, I got to travel around Europe in 1980, and it’s funny– we stayed with a friend of ours who was in the Air Force. He was stationed up near Banbury, England. There were rolling hills in this part of the country, and he pointed to this town where you could see little shadows off in the distance. He said, “That’s a little town called Chipping Norton. That’s where Gerry Rafferty cut the song “Baker Street”. That song was only 4 or 5 years old at the time. And lo and behold about 4 or 5 years later, I was in the studio recording with The Long Ryders!

It was fun to be able to get out. I was young when I was traveling over there then. Once again, it just opened your eyes to different cultures and life, to talk to people and get a different point of view. Of course, then getting to travel with The Long Ryders, with me Sid [Griffin], Greg [Sowders], and Tom, that was a tremendous experience, getting out there, playing your music, getting your art out there to the people, getting feedback, and we’re still doing it. I know this is about the Americana Railroad record, but we’re going to cut a new Long Ryders record.

Hell yeah!

Yeah, we’re going to cut a new album in July, so just in a few months.

What was it like leaving Virginia and heading west, to Los Angeles of all places? You said you’d never really envisioned making that sort of move to California.

So I moved out there, Charlie, with this couple. I was in a band in Richmond, and we were playing– it seems like this is all I’ve ever done– we were playing country western, honky tonk type material, but the band broke up, and this couple was moving to L.A. for a few different reasons. They said, “Hey, you’re welcome to come with us.” Well, I didn’t have a whole lot going on, so I said, “Okay.” We get out there, and we’re playing in these honky tonks. We landed in the San Fernando Valley, in a town called Reseda, which is actually where Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman lived about ten years or so before.

We were playing the honky-tonk circuit around the San Fernando Valley, and it was the same scene that Dwight Yoakam was on, the same circuit. You play these clubs on a Thursday, Friday, Saturday, then you’d go to one 3 miles away. I mean, that was a big area, a lot of people out there, and there were still a lot of the older musicians from the ’60s who were still playing. You’d get on, you’d have a drummer come in or a steel guitar player come in, and Pete Anderson, who went on to produce all those early Dwight albums, he played guitar with us a lot. The Palomino was the club that you wanted to end up at. We played there a handful of times before The Long Ryders. If you don’t know much about that club, that was a tremendous place. I’d go in there, and there’s Jerry Lee Lewis sitting at the bar, having a drink! Or you’re in there, and Waylon Jennings passes you, or Neil [Young]! Anybody, you know– a country rock ‘n’ roll star, country star that was 20-years older than me. That was just a great hang; that was the place where we would want to get to, the top of the mountain for playing that circuit.

To get back to the question a little bit more, I was really green, and I played with this gentleman for about 6 or 8 months, and I kept trying to introduce some original music, but he was not that keen on it. So I answered an ad in L.A. in Recycler, a classified kind of a paper. Sid had advertised for a band wanting a guitarist. The description of the band was “Buffalo Springfield meets The Clash.” And I said, “Okay, I could do that.” So that’s how that group started.

I met Carl a little bit after that, and we still have a great relationship. I just love her. She’s got a great bio and produced all kinds of people, collaborated with all the kinds of people, so I’m really honored that she calls me occasionally. We’re doing this new record that’s nearly done. I think it’s going to be great. It’s just really fun to think about getting that out there.

And so yeah, I was pretty green getting into L.A., and then luckily, with my friends and then with Sid, Greg, and those guys, we formed a great bond that we still have. It was such a great place to be, at least in those days, Charlie. There were so many studios and so many record labels. I was really in L.A. for only ten years, and it’s been 32 years since I’ve moved back, but I still have a lot of dear friends there, and I still go there a couple of times every year to record or to do a show or to play with somebody or to write with somebody. It’s really been one of the most important things in my musical career, to have that connection to that city.

What brought you back home to Virginia?

Well, what brought me back home was probably my father got sick, and then he passed away. And I thought, “Well, you know what? I see my parents once a year for a couple of days,” and also, trying to afford a house out there, the price was high and the cost of living and all that. I thought, “You know what? I’ve done my time,” and other groups were getting popular that I felt I had no connection to. I thought, “I’m a long ways from home, and maybe country boy might wanna turn his ass around and just go home and try to start a family.”

One could argue that Americana has always been part of our country’s musical landscape. There’s folk music. You also might think about rockabilly or Sun Record, and you mentioned the Lovin’ Spoonful as well. You know, some people might consider So Rebellious A Lover the first real Americana record. But it’s not a stretch to say that The Long Ryders were a galvanizing force behind the genre. What’s your take on y’all’s role?

There wasn’t a whole lot of that going on in L.A. There were country-type bands, and there were rock and roll bands, but the only band that really comes to mind right away that had a record out before us, that was in sort of the same genre, was Rank and File. We actually played together a lot. We’d go on little road trips up to San Francisco and play, with Chip [Kinman], Tony [Kinman], and Alejandro Escovedo.

I guess we were one of the first groups in and of that era that had this sort of post-punk sensibility. Sid and Greg had more of that, and I kind of came in with more on the country side, although I played in a rockabilly band back here. I actually played drums in it, of all things! But it had a natural evolution. Greg actually came from a band before The Long Ryders that was a ska band. There’s a song on our first EP where he’s actually breaking into kind of a ska beat, and I’m doing kind of a country thing. It’s an interesting mash-up of some different styles coming together, but it seemed to work.

I’ve always been fond of that. I think that it’s speaking to this intersection of country and rock ‘n’ roll music. You would have guys down south, whether it’s Charlie Rich or Jerry Lee Lewis who would be listening to the Black radio stations and feeling that influence. Of course, that was a major thing for rock ‘n’ roll, these white guys listening to these African American stations. That was definitely defining what they were doing, but I loved it when you would hear country and rock ‘n’ roll stuff find a sort of a cross-reference. You maybe have that happen in Memphis, maybe touched in Nashville a little bit, but that’s been an intoxicating mixture for me.

What’s it like seeing Americana, roots music, or whatever you want to call it, become an institution? It’s no longer a fringe or niche genre…

I think that it’s pretty natural for a guy or a girl to pick up a guitar and start playing,–at least in years gone by– a Hank Williams song, or some kind of a country song or a pop song, whatever, but I think that for a lot of people, it’s just a natural thing to pick up and kind of play some country kind of stuff. Of course, that’s changed because I don’t know what country is anymore. Modern country has become way too watered down, a sugary kind of pop music for me. I don’t really listen to it. I don’t really know much about it.

But I think that there was this whole field open for people who were kind of mixing older rock and roll and country stuff. That could have been someone who had George Jones and Elvis in their collection. And then, a guy might be going to the store and having those records on his turntable, so it might be somebody like Tom Petty, who has some country influences and some rock ‘n’ roll influences, or it could be a John Fogerty-type, listening to Buck Owens and having that be part of his music, with a louder guitar and louder drums.

We certainly didn’t invent it; we’re just another link in the chain. We just did it with maybe a little bit more aggression. We’re just in the middle there somewhere. And then we’re passing the baton off to somebody who comes next and they do it. Maybe they do it better than we do. You know, like Wilco who came after us that had some similar influences, and I played with a group called The Jayhawks…

Oh, yes! Their records are infallible, every single album. You were on Rainy Day Music?

Yeah, I was really happy with that one.

It’s a beautiful record!

Obviously, The Long Ryders are number one; that’s the main thing. It has been for a long, long, long time. But I’m on the new Dream Syndicate record. I’ve been on five or six of their albums…

I was hoping we would get the time to talk about your involvement with The Dream Syndicate. The last three records [How Did I Find Myself Here (2017); These Times (2019); The Universe Inside (2020)]– comeback records, if you want to call them that– are unreal. I thought the early stuff explored psychedelia, but these are truly experimental recordings. The new one [comes out June 10th]? Ultraviolet Battle Hymns and True Confessions?

Yeah, I am on that, and on the record previous to that. I’m actually kind of a full band member on that album. They recorded a number of albums about two miles from my house. It’s funny because they have a guy in Europe, and Steve [Wynn] is in New York, and Mark [Walton] is in Las Vegas, Dennis [Duck] is in L.A., so it’s planes and all that. I can almost get on my bike and ride over there, which is hilarious! It’s good for me because maybe if they were recording in L.A., I wouldn’t be involved. But Steve was actually in The Long Ryders before I was, and I guess maybe not a whole lot of people know that, but we didn’t have the name The Long Ryders at the time. He was friends with Sid and Greg, and he came and played just for like a week or so. They had a few rehearsals, and then he said to the guys, “Look, I’ve got this idea. I’m going to go form a band,” which became The Dream Syndicate shortly thereafter. And then that’s when I popped in. So I just knew Steve from around town. He’s a great guy. We’ve been dear friends for a long time and I went up and sang on one of their albums, Medicine Show, that was being recorded in San Francisco. I played on that and maybe one more in California. Then I’ve been on two or three of them here that were recorded near my house. With The Universe Inside, Steve said, “Hey, we’re just finishing an album. Can you come over, say, like 10:00?” I said, “Sure.” He said, “Here, let’s have a beer,” and so we just chatted, had some dinner, and he goes, “Hey, we’re going to go out and record. You want to come out and play with us?”

So we just recorded. John [Angello] was producing. They pretty much just turned the mics on, just hit “record”, and we came in. We just went straight through. I’ve never done this before: made an album, been in a recording session, with no one saying, “This is the tempo. This is the key.” There were no lyrics. We just played for about an hour and half, and Steve took those tapes back to New York. Then he added lyrics and the melody; he just formed songs out of it.

Unfortunately, it was made right in the middle of COVID, so there was no touring. There really weren’t much of any shows at all. But then they have this new record. I’m not nearly as involved in the new ones as I was in that one, but on the new one, I sing on a couple of tracks. I maybe played some pedal steel or something, but I love the band. They’re really great, and I’m just tickled to be involved with them.

During your career, you worked with some legendary performers, larger-than-life in terms of their impact on popular music. What’s your philosophy concerning collaboration?

Hang on… Let me think about this for a second… I think it’s really just bare bone, just a basic thought of getting into a room with somebody. Perhaps, “Hey, someone’s got a lyrical idea.” Normally, we’ll start with a chord progression. It could be a thought. It depends on the record. That record I just mentioned, that was all free form, everybody playing off of one another. So that wasn’t really any kind of conventional songwriting at all.

With Sid and I, it’ll be a combination of each guy either bringing in a fully completed song, or he would hand me some lyrics to put music to, or vice versa. Or, occasionally, not really so much as when we were all in the same town, you’d go over and say, “Hey, here’s a song. Let’s work on it.”

With The Jayhawks, I wasn’t really writing songs with them. Carla and I, just once again, you’re in a room, you’re locked in. It’s like, “What is the song about? What’s the theme? What are we trying to get to? What’s the emotional content here? Is it a country song? Is it a ballad? Is it an up-tempo rocker?” It’s a back-and-forth.

It’s been really difficult with COVID. Our bass player [Tom Stevens] in The Long Ryders passed away a year ago in January, and we wrote a tune for him, and that had to be handed back and forth via the internet. It’s challenging; it’s worth it. I think it came out pretty nice, but it is difficult. Nothing beats being in the same room with somebody, and you can react instantly off of one another, “try this, try that,” as opposed to where it’s like dropping a letter out of a helicopter, someone catches it, and it’s like, “What now? What was he talking about?” Nothing beats a face-to-face collaboration.

Artists are pretty eccentric, so you try to peel back those layers and get the best out of somebody, and hopefully, they’re doing the same with me. To me, it’s really exciting to just get a pencil. I’ve got my little studio up in my attic. I’ve got a whole room full of guitars, pedal steel, and banjos, whatever. But I think that the greatest thing you can have in front of you is a pencil and a blank piece of paper. Are you writing from the gut? For the soul? Trying to reach their mind? What’s the emotion that you’re trying to get across? What are you trying to plan in someone’s ear? It can come easy. It can be a struggle to finish the song, but it is nice collaborating with somebody because it’s like, “Hey, I wouldn’t have thought of that,” “That’s cool, Carla,” or “That’s cool, Sid,” or whoever you are with. My favorite thing to do is to write songs.

Would you like to talk about your upcoming album with Carla?

Sure, absolutely! So Saul and Carla have been after me for years for us to do a record. We’ve talked about it for a long time. Carla has had a few of these albums, Have Harmony, Will Travel. She’s gearing up towards a third one. On the second one, we did a song called [“Timber I’m Falling In Love”]. I was out there pre-COVID, and we had Ben Lecourt and Paul Marshall, and we were in a room booked out of Michael Reed Studio out in Woodland Hills. We were going to do the song. I don’t know if you’re familiar with “Timber”…

I know the Patty Loveless version…

And Vince Gill cut it. It’s a pretty up-tempo song, and Charlie, the way I look at it is why do a cover of a song exactly like the song? You’re not going to top Vince Gill or Patty Loveless! Other than a bit of me coming in and playing guitar on her and Gene Clark’s record, that was something that we did, say probably in 2019 when we did those sessions in L.A. We cut 2 or 3 songs. We thought, beyond these songs for the compilation album, maybe we should do some more. It took us a little while, and we got together last fall at Robby Krieger’s studio. We had a different drummer, Mitch Marine, who is actually Dwight Yoakam’s drummer, and Paul came back in. Skip Edwards came in– he’s played with everybody– and Carla came in. We cut 7 or 8 songs over there to add to the few that we cut pre-COVID. We thought we had an album there. We went out and did one other song a few months ago, but it can be time-consuming just because you’re sending files back and forth. The bulk of it was cut in L.A., but it can be time-consuming because you’re working long-distance.

I love playing. I love singing with Carla. She’s great; Saul’s great. They’re really driven, creative people, and they could not have been more kind. They’ve always been very supportive of me, and I’ve always been appreciative of that, so finally we’re getting this record nearly done.

Americana Railroad lands across all major digital platforms on June 17th! Like & Follow The Long Ryders for album and tour updates!

Charlie Farmer is a Georgia writer and professor who loves his wife, his daughters, his students, his cats, his books, his LPs, and everything else one should love in life.