While Lee Hazlewood’s name often makes the list of pop’s most criminally unknown figures, many listeners are already unknowingly acquainted with his handiwork. Thanks to VH-1, I was introduced to the Hazlewood universe when I saw the video for Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walkin’”, a seductive go-go whose dizzying descending bass line distanced the song from any pop number I’d heard before, retro or contemporary.

I had no idea that the man behind the tune– Lee Hazlewood– was a Korean War vet-turned DJ-turned singer-songwriter and producer who had discovered Duane Eddy, one of rock n’ roll’s original guitar heroes, co-written some of his most famous songs, including the archetypal “Rebel Rouser” and “Cannonball,” and engineered his reverb-laden sound. Dean Martin covered his song “Houston”, a hit that afforded Hazlewood the industry cred and goodwill to work with Dean’s son’s trio, Dino, Desi & Billy. None other than Frank Sinatra, admiring Hazlewood’s Midas touch, enlisted him– perhaps with an offer he couldn’t refuse– to jumpstart his daughter Nancy’s career. The results: a handful of classic albums and the essential bizarro hits “Some Velvet Morning” and “Summer Wine”. In the meantime, Hazlewood’s label LHI (Lee Hazlewood Industries) issued the International Submarine Band’s lone effort, Safe At Home, a record that not only introduced a young Gram Parsons but also stands as one of the first country rock albums.

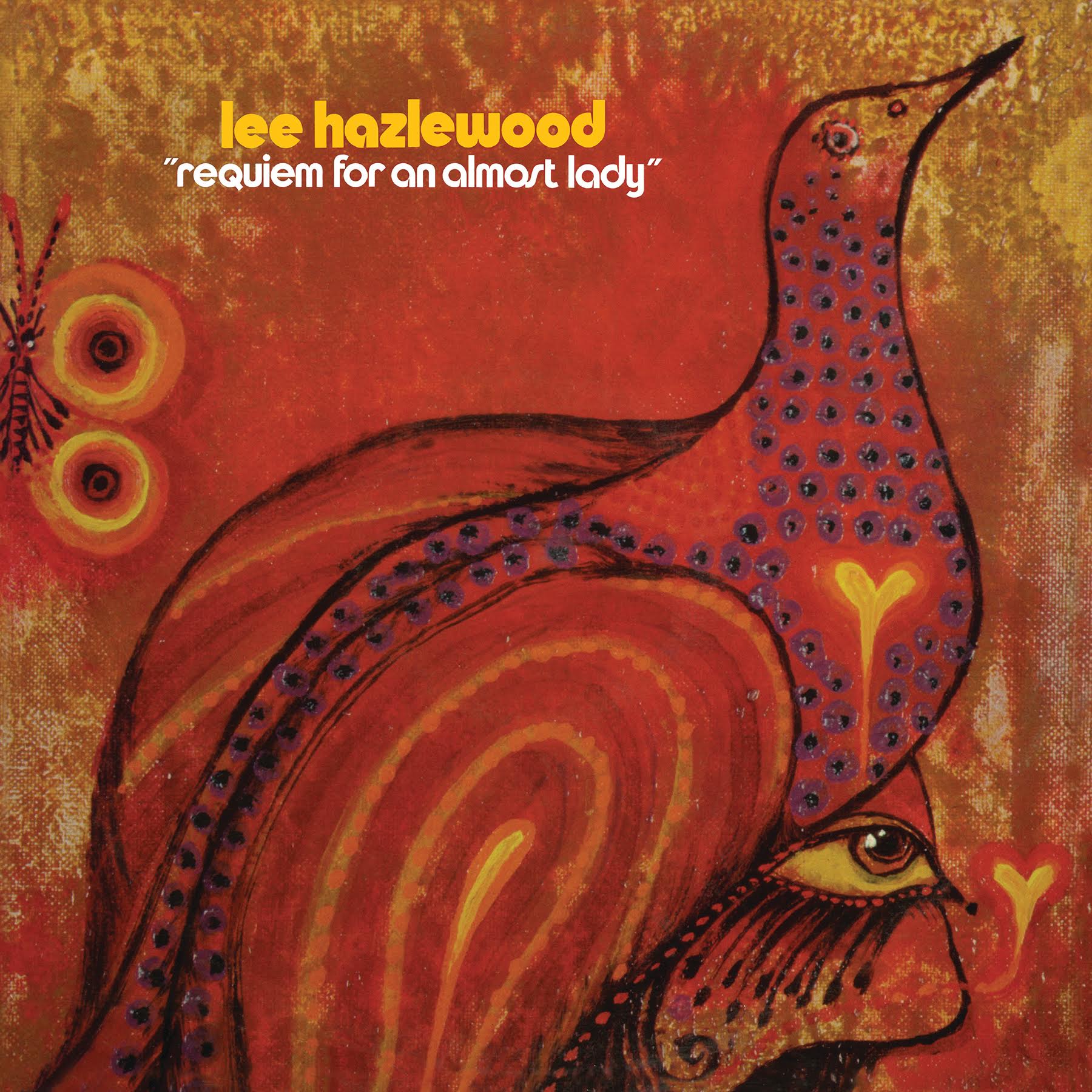

Hazlewood also continued to produce his own largely acoustic records, loose concept albums too idiosyncratic for mainstream audiences, including the Winesburg, Ohio-esque Trouble Is A Lonesome Town (1963), The Cowboy & The Lady (1969; with Ann Margaret!), and Cowboy in Sweden (1971). Yet it’s 1971’s Requiem For An Almost Lady that’s his most complete and most haunting, an album that yearns for closure that never comes.

Hazlewood’s spoken-word intro for Requiem’s lead track “I’m Glad I Never…” sets the scene: “In the beginning, there was nothing, but it was kind of fun to watch nothing grow.” The language is Biblical, a paraphrase of Genesis’s opening lines. One might accuse Hazlewood of melodrama or tongue-in-cheek hyperbole, but his voice never wavers; per usual for Lee, this is serious business, the speaker a Lazarus or Ancient Mariner-type who needs to tell his story. In this trademark baritone, he begins to sing, the verse ending with one of the most heartfelt blasphemes you’ll ever hear:

You came walkin’ into my life

Carryin’ your own dreams

You could’ve been

Yeah, you could’ve been good

Then why were you so goddamn mean

Then our speaker reveals why we should be happy: “But I’m sure glad I never/Ain’t you glad I never/Be glad I never owned a gun.” Just like that, we have both a creation story and an almost-murder ballad. From this inauspicious opening, Requiem For An Almost Lady mourns across 24 bitter minutes, dwelling in memory and searching for resolution.

Hazelwood said that the album isn’t based on one failed relationship but is a cumulative narrative. The accumulation of heartbreaks paralyzes. In “If It’s Monday Morning”, our speaker wakes up in jail– again– hungover, bleary-eyed, dry-mouthed, oblivious to what got him here. We can still taste last night’s last call and the cold sweat across our brows as we piece together the latest humiliation. His plan: “I’ll probably get stoned.”

In “Won’t Tell Your Dream”, our speaker loses himself in routine:

I’ve learned to do some simple things

Like lock the door and shut the lights

And pay the paper boy on time

And try to miss you less each night

But the holding pattern doesn’t lessen the blow, nor does the last-ditch plea of “Come Home To Me” or camaraderie among other heartbroken men in “Must Have Been Something I Loved”.

The agony overwhelms in “I’ll Live Yesterdays”, the album’s most emotionally devastating track. Each song begins with a spoken word preface that provides some context– justifications, apologies, blame. In this case, Hazlewood says, “Seems we’re always doing something to hurt each other, but you know you never really hurt me until the 4th verse of this song”. By the time he finishes the verse, we understand he’s grieving an abortion.

“Little Miss Sunshine (Little Miss Rain)” offers a momentary respite, a singsong charmer that wouldn’t be out of place on a Wes Anderson soundtrack. Despite the glimmers of hope and compassion here and in “Stoned Lost Child”, Requiem is a breakup album without closure, a record for those who aren’t ready to dismiss grievances.

It’s this Blood On The Tracks bitterness that gives the album its staying power. Requiem’s Revelations to its Genesis: “I’d rather be your enemy than hear you call me friend.”