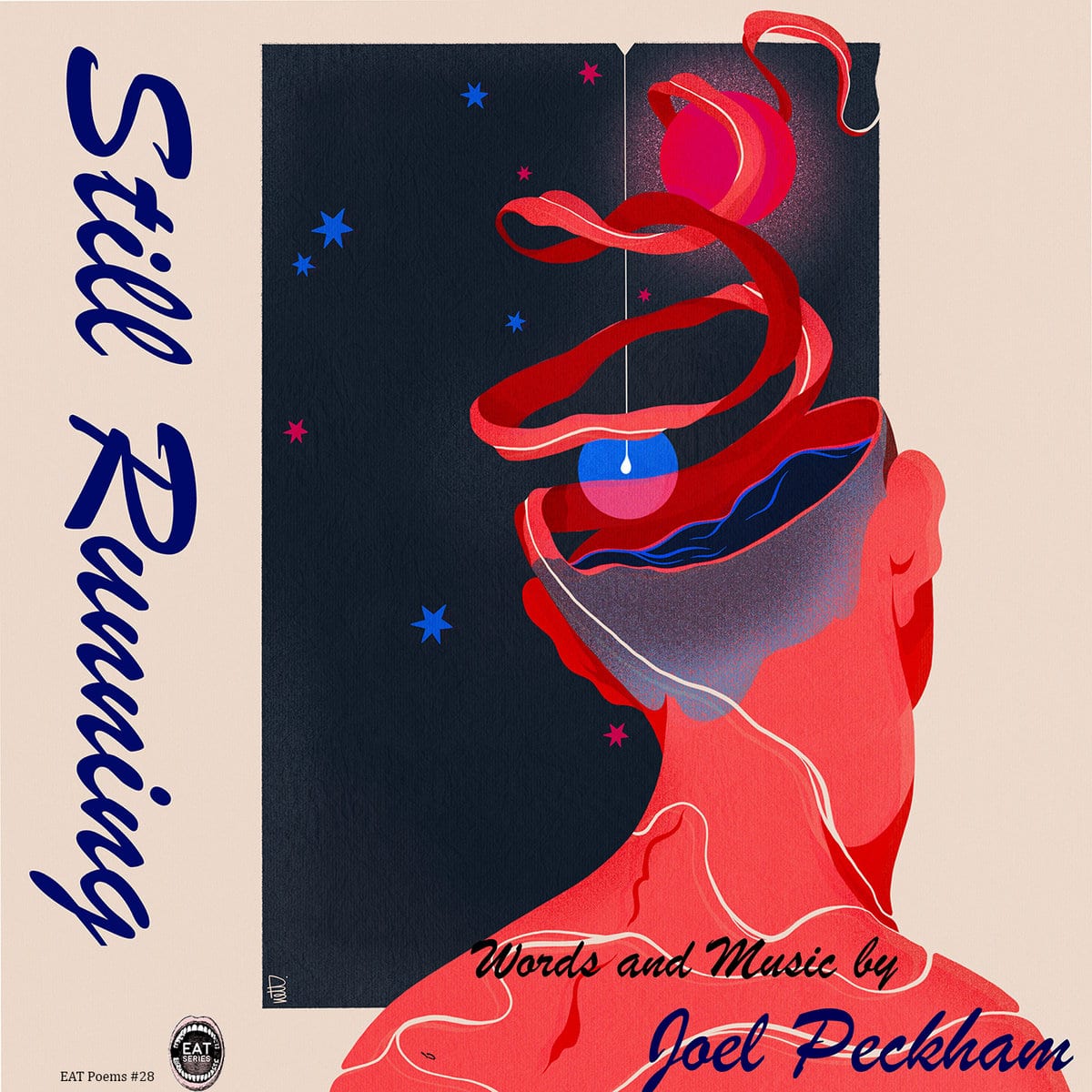

I’m not sure what’s more shocking– Joel Peckham’s Still Running or that it took him this long to craft a poetry-rock n’ roll mashup. If you know Peckham, the eventual marriage of these seemingly disparate mediums felt inevitable. Yes, he’s the author of nine poetry and nonfiction collections, including last year’s Much and Bone Music, works that deal in memory as Peckham manages its wreckage and emerges as living proof of something I want to call miraculous. But anyone who’s spent time with him knows he’s also a fine guitar player with a malt shop croon of a voice, the kind that gave Sam Philips fits as he wondered what he could do with Roy Orbison. He’s a believer in the three-chord rumble and the big beat who’s threatened a band for years, and with Still Running, he’s delivered on that promise, even if unconventionally.

There’s no shortage of records featuring poets accompanied by musicians, but so many of those follow an exhausted template– the poet reading as jazz sax adds occasional punctuation. Here, Peckham replaces cocktail lounge stylings with shards of chords, feedback, swirls, and Nuggets-friendly fuzz and beats, creating textures that envelop his poems/songs/lyrics of excavation and renewal.

Peckham identifies as a cynic, but when he says that, I believe he’s either imagining himself a Johnny Strabler-type or selling himself short. Still Running, like his other collections, is nothing if not a celebration of somehow still existing.

CF- Can you talk about the origins of Still Running? You’ve published several books of poetry and a collection of essays. But this is something completely different. How did you decide to combine poetry and music?

JP- I’ve never played music that professionally, but I’ve been playing for a long time. I’ve gotten the opportunity to play in some bands. But like everybody else during the pandemic, I was trying to find stuff to do with myself when I was locked in my garage, literally, and trying to stave off anxiety that way. I started recording again, and basically what happened was I’d been trying to record a song called “25 Miles”. It’s an R&B standard that I love. I got all the backing tracks done, got the whole thing done, and then realized I had played it in a key that I couldn’t sing in, so I couldn’t do the recording. And then I was wondering, “What am I gonna do with all this?”

I don’t really have a plan when I sit down to write, so I started writing, and then I started writing about being able to sing the song. It became about something much different, more about how one of the reasons I can’t sing this is because I don’t have the experiences– I don’t know what it’s like to be so poor that I’d have to walk 25 miles anywhere, never mind to the person I love. I don’t know what that walk would be like. So I started writing about that and thought it’d be interesting to record this vocal over the top of the recording. I liked the results. It was pretty basic; it’s not a complicated song. But I liked the feel of it. I’ve heard a lot of poetry backed by loose jazz or sometimes some music that has an ambient electronic-folk quality to it. I’ve heard a lot of that– I’m not going to critique what other people are doing– but it doesn’t appeal that much to me because the music doesn’t have any of its own integrity. It’s not in conversation with the work; rather, it’s just in the background.

When I did this first, it was rock. I’ve not heard anybody do poetry backed by rock. And I started thinking about how I might do this with other pieces of mine. Initially, it was writing or seeing what I’d recorded and things that were my own musical compositions and how they might fit with things I had already written. It got to a point where it started becoming almost like I was composing music while I was writing the poems, or listening to the music while I was revising the poem, and that became a very different thing, but I stuck with this idea the music had to have its own integrity. It wasn’t there to just back up or add little flourishes to the poetry. I really wanted it to have a coherency, to have actual song structure, to have choruses and vocals, and– I’m not the greatest lead guitarist– solos, occasionally. I was trying to figure out how to incorporate those elements so that they were speaking to each other. That really excited me because writing this is all about radical juxtaposition. It’s about putting one thing next to a different thing and then creating this third thing. So is music, really. That’s what harmony is, right?

So I started thinking about how I have could have the music do that with the poem. I kept going, and then I suddenly realized that I had 35 minutes of material. It was pretty organic. A lot of the subject matter was about isolation, so it was very much a pandemic project.

Did you have any reference points in mind, albums where a poet has successfully blended words and music? You mentioned the poetry-backed-by-jazz records, and even with the best of intentions, those are cliches at this point. More often than not, they sound like an NPR segue way.

Not that it was a reference or an influence– it’s a very different project– but I think of Ross Gay who’s using other contemporary musicians. Jose Gonzalez did backing music of his work. And I’d say this seems like a weird reference, but the first exposure I had to something like that was Gil Scott Heron, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and that stuff. He’s a legit singer and a musician himself.

There is Allen Ginsburg’s “Ballad of the Skeletons”. I tried to listen to that, and it didn’t do a lot for me. I really don’t have a strong reference for exactly what I’ve done here, except that it’s all of those poets I love who are always intensely musical. I listen to a ton of poetry. I’m listening to Jericho Brown’s New Testament right now. I listen to a lot of Danez Smith and Hanif Abdurraqib. There are just so many great poets that have a musicality to them.

And you know I’m a music nerd. I’m obsessed with American music, so it started really being an exciting thing too to think about what genres were appropriate for each piece that I was writing– like this is a bit more R&B, or this is a bit psychedelic, or this is a bit more garage rock, and I even took a shot at punk. I don’t know how successful that was, but I was incorporating influences in music that I love and grew up with.

How do you juggle the two impulses– loving poetry and music? Do you ever feel like you’re cheating on one with the other?

For me, it’s all about how much time you’ve got. I don’t feel like I’m cheating on one. I’ve got a writer’s group coming up, or I’ll have a deadline or something, and with poetry, there’s a schedule to that for me that is a bit imposed on me by the world I live in, in the circles I move in. There’s an expectation I’m going to produce. Nobody at my academic job cares if I write another song. I don’t get credit towards tenure for that. In the last two years, music has been the thing I do that I don’t have to have those concerns about. It’s a place I can go to that feels very centered and away from a lot of things, but at the same time very connected to a lot of things.

It’s that weird thing that you look for in the meditative arts, to both be completely centered but also fully connected, while at the same time not distracted. Flow, right? I find that in both writing and in music. But when it doesn’t happen in writing, I can feel a little panic happening, and with music, I don’t feel that kind of panic, maybe because I haven’t done as much of it. I’m still in this discovery phase with it where I’m a little less hard on myself than I am with my poems, although listening back to things, especially when it’s coming out, you listen to it again, hear every damn thing that you would fix if you could touch it again. But I had to accept that since I made the commitment to doing this all by myself, for the most part, I had to accept that it wasn’t going to be perfect. That might even be part of its appeal. But it still stresses me out, man!

With this being a pandemic project, I was wondering if these songs came instantly. Did you know right away that you needed to document what was going on, that we were living through something historic and significant and catastrophic?

I’m kind of a cynic that way. There was a moment where Rachel and I were walking across the parking lot to Kroger, and we had our masks on, and she’s like, “Did you ever imagine this would happen?” And I said, “Oh, yeah.” I couldn’t believe it hadn’t happened yet. And I don’t want take us into a doom place, although “This Year’s Child” touches on that. The planet’s in trouble, you know? And it’s not helped by our poisonous politics. It’s hard not to constantly kind of walk around waiting for the next shoe to drop. I’m not waiting for it to happen, but I anticipate it. I realized once my kid had to come home from college, and all of a sudden he’s taking his college classes from the upstairs bedroom while I’m teaching my college classes in my boxer shorts in the downstairs basement, all of a sudden you realize, “Well, something is happening now, and it’s not going away anytime soon.”

Other than the sort of existential terror of it, there were some beautiful moments, which is a weird way to say something. But there were some beautiful moments within that. I felt very blessed to have a family. I know as a father, it’s sort of a strange thing because at once, it makes you feel more panicked because you’ve got kids, you know? And if it’s just you, who cares? But if something happens to your child or your wife, your partner, that’s different, so you feel very exposed and vulnerable because something could happen to this other person, and you might even be the cause of it. But there’s also an incredible intimacy. You just have to spend time with each other. I’m playing music with Darius, and I’m writing poems with my son and sharing them. We all had a family reading time. I’m not going to say I miss being locked down, but it’s interesting how we adapt. I created a lot of art during that period and reconnected with myself and Rachel and Darius. We were connected, obviously, but more than we would have been otherwise.

Almost all of this was written, at least initially, and conceived during that lockdown phase of the pandemic, where Rachel might come driving home and the garage door would come open, and I’m there in my boxer shorts with headphones on, playing the bass. However dark the material you’re working with is, it’s hard not to have a sense of joy or laughter at the absurdity of it all. There were some things I was grateful for having gone through.

You talked about recording in the garage. What was your recording setup like?

It was a garage! There were lots of mattresses, trying to dampen an echo because it’s concrete in there, although sometimes I loved that echo. I had a couple of different modeling amps. It’s really simple guitars because I love cheap guitars, trying to get interesting sounds out of them. I have an Epiphone and a Gretsch Junior Jet Bass and my big old Fender box of an acoustic-electric. The setups were simple. Sometimes I plugged in; sometimes I used the area mics. The vocals were tough because I was in a garage. I’d find myself having to rerecord things because you could hear the delivery truck outside. Sometimes you’d leave it in. It was an interesting experience, but it’s heavily layered, which is why it definitely sounds like garage music. In some cases, that’s kind of intentional. There are some things that sounded, on first listen, too clean to me, so I changed a microphone to get a bit more of the room in the track. But it’s just a lot of very basic moving microphones around and trying to figure out distance. I mostly used Logic Pro to mix the whole thing and then send it off to someone else to remix it.

It was an interesting process because if I had wanted to take myself down to the studio, I could have used the university resources, but it wasn’t really what I wanted to do with this and of course, while I was doing the first four or five tracks, I didn’t realize I was making an album. I was making something with very little sense of where it was going to go. I was learning on the fly in a way that was really freeing and exciting. That can really help you in some ways not get locked into a way that you think something is supposed to be done. It definitely changed my relationship with learning to play bass. Thinking about how I might want to use that instrument in various ways was really interesting to me. There’s some functional bass on this, but it’s mostly used to carry a melody, which also might come from listening to a hell of a lot of the Beatles during the pandemic as well. That melodic bass that McCartney plays, it’s hard to get that out of your head or to not want to try it.

How did you determine what music suited a poem? “Still Running”, for instance, has that garage punk vibe; “Virtual Sermon” is more psyched-out. Did you improvise the pairings, or were the relationships more premeditated?

With “Still Running”, definitely the minute I wrote it, I wanted to set that to something because it felt like a rock song. Everything about it, even reading it without the music felt that way. I had a track where I loved the music but was deeply unsatisfied with the lyrics. So I kind of worked with that. “This Year’s Child” felt obviously like a punk song to me, so I tried to get something very aggressive about that and simple in terms of court progression. It was definitely written almost simultaneously with the music. “The Wave” was a completely separate song. What happened with that was I had written a song, and then I was listening to the song when I wrote the poem, “The Wave.” I liked the way it spoke with that particular rhythm because that song is about trying to find these moments of joy in an otherwise tragic circumstance, among loss, among grief, among lots of suffering. Those ideas of, “Am I allowed to feel joy here?” and “Where is joy possible within this?” and “What does joy mean in the context of all of that?” I thought that the music set with those ideas was a lot more interesting, that they spoke to each other in ways I really liked.

So there are pieces there definitely where it’s matching a pre-existing track to the poem, but there’s also a whole bunch of things like “Virtual Sermon”, definitely a poem written along with the music. And I don’t know even know what genre I’d call that one, other than it started with a bass riff. I liked the way it moved. It sounded ominous and throbbing. It has this heaviness to it. And then I wrote the lyrics in response to the poem, which are straight out of the Bible really– the “Eli Eli Lema Sabachtani?” Somehow things came together on that, but it’s funny because it seems entirely appropriate on the one hand and completely inappropriate another because the poem’s about watching someone give a sermon on television because they couldn’t go because it was Easter. It was such a strange thing. And the music does not sound like church music at all. It’s like the furthest thing from it, but at the same time, it’s kind of what I would do if I had to make church music. This is what it would sound like. And then, of course, there’s two more folk-psychedelic things with “Any Moonwalker” and “Wow! Signal”.

I feel your poems are associative– way leads on to way, as Robert Frost says. You have these disparate events/scenarios/motifs that eventually find their way to one another; they go home together. Is that what Whitman means as a mystic– giving yourself over to the unplanned?

Yeah, I’m fascinated with what I call drifting. I think this is true, not just with poetry but lyrics. With Thin Lizzy, some of their lyrics have this drift quality, and sometimes actually even through some of those early Springsteen songs. But I love this idea of a poem that can associatively drift. We tend to think about poetry in terms of metaphor and symbol, and that it’s reaching in and down, but a poem can also make these lateral movements and shifts, and it’s through those shifts that you get a certain amount of accumulation. Now, it’s very hard to do in a short space, but I don’t write short poems.

I really like the idea of being expansive. and Whitman, of course, is a guide– but so is someone like Dean Young. His discussion of mutation as evolution, you know, that trusting the kind of almost random way the human mind works, the way you walk past the turned-over garbage can and all of a sudden mentally it’s 1992 or something. You’re walking down some street and trusting where your mind goes. That’s how we make meaning. We’re never in a single moment. Every moment is layered upon every other moment, and every life is and every sound is. It is through those associations and connections that things have value. There’s nothing inherently valuable about anything, except for the connections we make.

Does relying on drifting ever frighten you?

I get frightened that I might never find my way to a resolution. But I sort of let go of that fear a long time ago. There was a time where I was very concerned about the idea that it’s not a poem if I can’t keep it all on a single page, sort of like it’s not a song if it goes past two minutes and 45 seconds. There are a lot of people who will stop reading at a certain point, stop listening at a certain point. It’s just not going to be interesting to them. But I think for me, it’s that discovery and surprise and the journey itself that is so interesting to me. I do cut out a lot. This is the funny thing– I write long pieces. They start out five pages long, and I cut them down to two or three. What I want is for my readers and my listeners to feel like they’ve been taken someplace and that it wasn’t the place they expected to go. They’ve just found themselves there, somewhere unexpected. Hopefully, it’s a good place. It isn’t always, but that’s growth.

“How to Listen” contains the lines, “I want this music I have made in my garage to be a different kind of listening, thick with ghosts and echoing.” Is that your mission statement as a writer?

Yeah, I’m fascinated by listening as a concept. There’s a great book about teaching creative writing called The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop by Felicia Rose. She talks a lot about deep listening and what that means. In some ways, Still Running is a very narcissistic project– it’s a whole lot of Joel Peckham. But everything that’s coming out there is a product of this kind of almost radical openness, which is what I mean when I’m talking about listening. If being an artist is anything, it may seem pretty egomaniacal, but not when you are in the place where you are fully a receiver. In “Wow! Signal,” there’s that whole symbol of the satellite dish that’s receiving these signals, and I’m thinking about what does it mean to actually not only hear something but make the effort to really hear it and try to find a way to understand it to the extent that it’s humanly possible. And that’s tough because that means you have to be super receptive. It also relates to that technique of drifting, which means that you realize you have to trust and be willing to give up control.

I think that line is very much a mission statement for me as an artist and as a writer. I’m a very good talker, but I’m much more interested in listening. It’s a fascinating way to interact with the world. When I was a kid, I used to sit and close my eyes and try to identify all the things I could hear, wherever it was. It’s still something I do. The world is never silent, you know? The only way the world will ever be silent is if we blow it up. There’s always something, and I’m fascinated by trying to hear it all.

Another line that hit me is from “Still Running”, “My secret is I could not love you without first and always imagining you gone.” Could you elaborate on that line? Is the threat of loss an essential for you? To love? To write?

Perspective is earned by living, and for better, for worse, I’m not the only person to have been through some shit. I lost my first wife [Susan Atefat-Peckham] and my oldest son [Cyrus] in a car accident. That’s a fact; that’s a thing that happened. I live with it, and it’s easy to put that into its own place and make assumptions about what that experience might be. But what that poem is about is that I was almost ashamed at how happy I was to be alive. Here I was– I’d lost my son and my wife. But I’d have these moments of just incredible joy, even though I was in a lot of physical pain because I suffered some injuries in that accident. To simply be able to eat a donut or drive a car or roll the windows down and listen to The Rolling Stones… It was a miracle that I survived the accident we were in. Every day was a bonus, but it also does color everything I experience. I am a person who when friends walk out the door, it’s impossible for me not to wonder if that’s the last time I’m going to see that person.

I know I can’t capture things or hold on to things. I don’t even think that’s what art does. That would be to fossilize the thing. I think what we record is the vanishing, that maybe all art is a bit obsessed with that ephemerality, that beautiful thing that can’t stay. I’m very interested in trying to fully understand and fully experience especially the people I love, but everything I love while I have it. I know very well that I might not have it long. It is the perspective through which I see the world. I still wake up in the middle of the night, frantic because I don’t know where Darius is– my son who survived. My wife Rachel has to calm me down and tell me that he’s safe, that he’s in Boston going to school, but it will always be a part of me.

In “The Wave” and “Any Moonwalker Can Tell You,” you’re writing about your father, who’s in the last stages of his life. What’s it like trying to capture the past few years with him?

I don’t know. It’s beautiful and painful. I’ve been writing a lot. There’s a whole sequence of poems I’m doing called “Any Moonwalker Can Tell You”, and one of the tracks from Still Running is one of those poems. Most of them are about him and about memory and dementia and trying to both appreciate someone and grieve them while they’re still there. The last few months have been difficult, but they are there filled with their own beautiful moments. It isn’t impossible for me to talk about, but it’s hard for me to talk about it coherently, and I think that’s one of the reasons I allow myself to write about things. It’s really difficult for me. People ask me, “How is your father?” and I have no answer for that. There are no words to find for that.

I’m not the person who can ever just say, “Fine.” I don’t know how to do that. But in a poem or a song, I think I can map out my way to doing more than just surviving it. I can find ways to explore it, to feel it, to make something out of it that I can step away from and look at it. It’s not catharsis, and it’s not control, but it’s just fully allowing myself to experience it in a way that I know is safe for me. It’s not all I write about, but I’ve written a ton about it. I’ve always said to my students that the recipe for writer’s block is to try to write about anything you’re not thinking about, so if you’re constantly thinking about something, tough luck, that’s what you write about. It’s too bad for you if it’s making you miserable, but avoiding it will make you more miserable, and that’s for sure.

And music is so physical. It’s such a physical thing to do, to sing. The body, the breath, the vibrations, the tone. It’s so powerfully physical that it’s almost impossible to create something that’s not going to be heavily influenced, something heavily embedded in your experience. And if you try to run from it, you write crap. You’ll just write a whole lot of crap that’s empty and feels like a computer could have done it. But I lived this album; I made it.

Joel Peckham is a professor of Regional Literature and Creative Writing at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. Still Running is available via EAT, Bandcamp, Apple Music, and Amazon Music.

Charlie Farmer is a Georgia writer and professor who loves his wife, his daughters, his students, his cats, his books, his LPs, and everything else one should love in life.