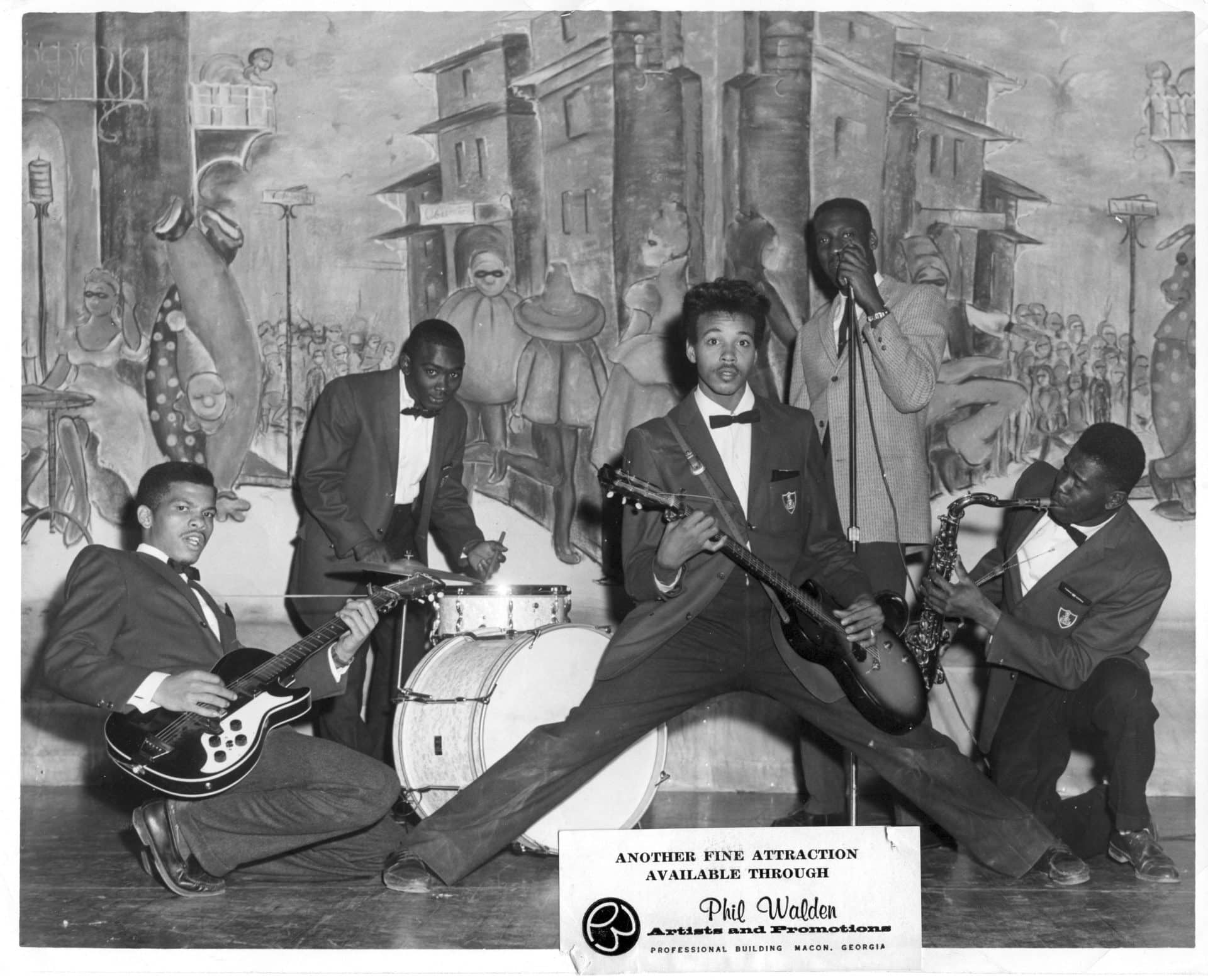

For the past twenty years, I’ve had the same picture taped to my office door– a black and white promotional photograph of The Pinetoppers, a midcentury Macon R&B combo led by guitarist Johnny Jenkins. It’s as iconic as Tom Copi’s 1970 image of Iggy Pop, smeared in peanut butter, approaching levitation, in Cincinnati, or Jim Marshall’s 1969 shot of Johnny Cash, asked to pose for the San Quentin warden, flipping the bird at any request for civility. In the Pinetoppers’ photograph, staged as it is, the band, sartorially inclined, is caught red-handed, each member brandishing his instrument. Jenkins is the centerpiece, his legs split in a power stance, his guitar slung to his left, anticipating Jimi Hendrix, his eyes under the spell of an old hypnosis. Here, even in this freezeframe, he suggests perpetual motion. He is on the verge; he’s the embodiment of rock n’ roll’s early promises.

As the 1960s began to fade, Jenkins was light years removed from that photo’s bloom and dash. The Pinetoppers were a distant memory, promises unfulfilled. Their explosive 1960 debut 7”– “Fat Girl”/“Shout Bamalama”– featuring Otis Redding, the band’s driver, on vocals was a stunner, two of the most frantic R&B songs ever committed to wax. For reasons unfathomable, the songs failed to resonate with a national audience. Their 1962 follow-up, a double A-side, featuring two joyous instrumental workouts, “Pinetop” and “Love Twist”, faired no better. Later that year, the band traveled to Memphis to record at Stax Records, and Redding, taking advantage of some post-session downtime, recorded “These Arms of Mine.” Jenkins briefly remained in the picture– that’s his gorgeous staccato guitar on “These Arms”, not Steve Cropper, as many believe– but he declined a relegation to Redding’s backing band, citing a fear of flying.

By 1970, Jenkins had eased into the role of the rural bluesman, but Capricorn’s Phil Walden and Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler had other ideas. Hoping to capitalize on Dr. John’s gris-gris chic, the two decided to rebrand Jenkins as a voodoo-inflected troubadour and send him to Capricorn Studios to record his solo debut LP, Ton-Ton Macoute. Another version of the album’s origins asserts that it began as a Duane Allman solo record, and Jenkins was given the chance to salvage the session’s scraps. While historians might confuse the album’s impetus, those in the know agree that Jenkins was a nonentity during the recording sessions, showing up sporadically to add vocals as needed, singing over rhythm tracks laid down by a rhythm section whose impending fame would overshadow the final release. In his autobiography My Cross to Bear, Greg Allman writes, “Duane, Berry, Butchie, and Jaimoe all appeared on [Ton-Ton Macoute]. My brother played his ass off.”

Soon after the record’s release, Jenkins disowned the project, telling The Great Speckled Bird, “I wasn’t there with the guys when they were making the rest of it, you know. More blues would be my style if I had been there. Actually, it would be ALL BLUES because that’s my feeling, you know– the blues. This psychedelic idea came through the guys at the studio, you know– it goes along with what’s happening in the world today, you know? But really, you can’t make a person what he’s not, you know. A fellow has to give out what’s inside him.”

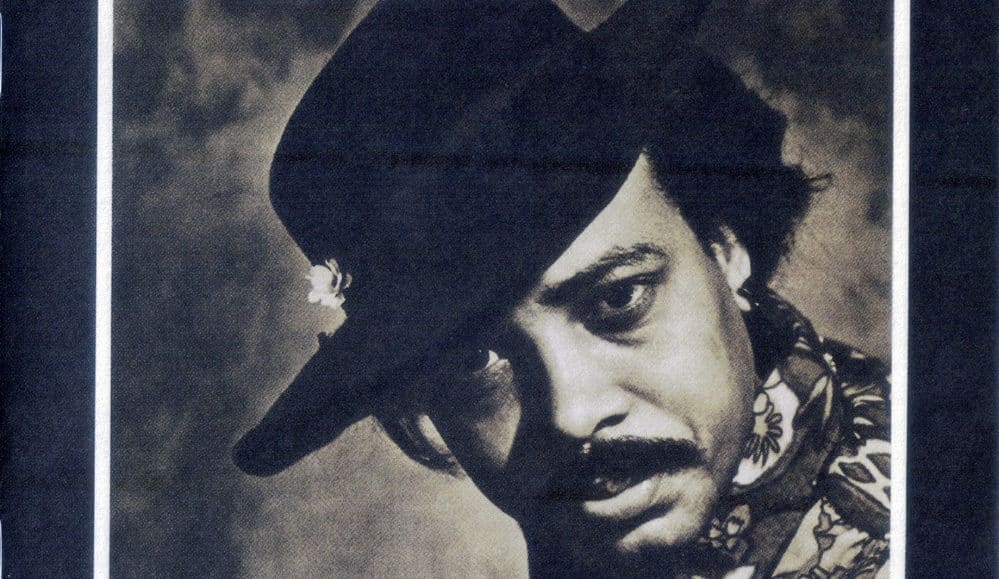

Perhaps Ton-Ton’s album art best captures the gulf between Wexler’s and Walden’s and Jenkins’s intentions. The cover features Jenkins serious and sharp, his flower-adorned fedora and floral shirt not out of step with Louisiana suave. The gatefold’s inner photo– a down-in-hole shot of Jenkins alone in the studio with his acoustic, belting out a song– tells another story, that of the solitary bluesman working with the only tools he needs.

Jenkins’s disavowal of Ton-Ton– as justified as it might be– is unfortunate because it helped diminish the legacy of one of the era’s most original and influential albums. As chaotic and impersonal as the recording sessions were, the album’s night-tripping grooves are raw, deep, and bewitching. The voodoo vibes and NOLA influence never feel contrived. The album opens with a cover of Dr. John’s “I Walk on Guilded Splinters”, and within seconds, its lazy-ass drums (later sampled by Beck, Oasis, and Wu-Tang Clan) accomplish the sublime.

The rest of the album reaches for similar transcendence– versions of Muddy Waters’s “Rollin’ Stone”, Bob Dylan’s “Down on the Cove”, and John Lee Hooker’s “Dimples” align more with Jenkins’s ideas of the blues, but are hardly customary bar-band takes.

Elsewhere, Jenkin’s channels Hendrix on “Voodoo in You” and delivers street-fightin’ funk on “Bad News”. Most importantly, the minimalist funk-blues of “Leaving Trunk”, “Blind Bats and Swamp Rats”, and “Sick and Tired”, with their bare-bones percussion and unapologetic repetition, provide the archetype for the essential fucked-up blues of future shocks like The Gories, Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, The Immortal Lee Country Killers, and countless other second, third, and fourth-wave adherents that too believed in rock n’ roll’s promises.

Ton-Ton Macoute does what few albums can– deliver to listeners the thrill of the familiar and the unfamiliar, at once sending them to the revered music of their past while convincing them that they’ve encountered something wholly new, a discovery they alone– for a moment, at least– are privy to.

Charlie Farmer is a Georgia writer and professor who loves his wife, his daughters, his students, his cats, his books, his LPs, and everything else one should love in life.