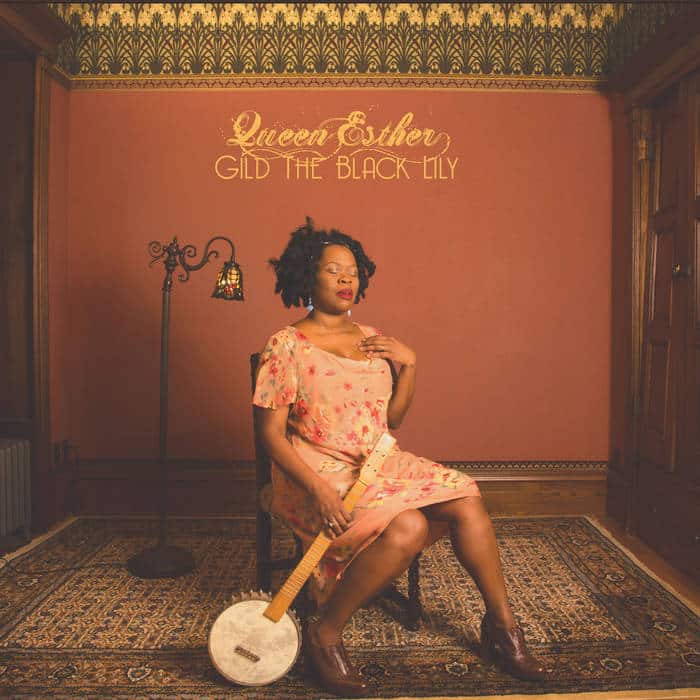

Queen Esther’s Gild the Black Lily combines the bruised nostalgia of ’60s country with the defiant voice of 21st Century rebel soul. From personal compositions to reimaginations, each song and tale is rooted in what Queen Esther relates as twang, the sound of a South built on African culture and blood that reaches across centuries and continents to define the American musical identity. She calls it Black Americana and it’s as much blues as it is honky tonk, gospel as it is rock n’ roll. An accomplished all-around performer, Queen Esther’s journey has led from her home in Georgia to the University of Texas to New York City where she currently resides, and continues to explore the stage as an actor, a playwright, and a vocalist for numerous projects. Gild the Black Lily is available now!

AI- I love the album and I confess that this is my introduction to you. What I have learned is that you’ve had just an absolutely amazing career thus far, and I wasn’t sure where to start! I think the new album, Gild the Black Lily is the place to begin. Tell me about when you put this together. Was this something that was simmerin’ before the lockdown, before the quarantine, and COVID-19? Or is this your pandemic project?

QE- Oh, no, this is not a pandemic project. This has been simmering on the back of the stove for a while. I started to do some deep digging and reading and research about all things Southern. Little things would pop up and I’d write a song and I’d play it with my band and then that would turn into a set and I would just sort of play it and roll it around and let it turn into whatever I wanted to be. But that went on for a while. I think the reason why the album sounds so good is because all of those musicians, I’ve been working with them for years anyway, but they’d been playing those songs for quite some time. So it wasn’t, like I said, “Hey, you guys, I got these songs and we’re gonna go into the recording studio after we rehearse for three days and just knock this out!” They’ve been living with them in a way just like I had.

When were you puttin’ all this together? When did you go into the Mighty Toad Studio and record the songs for Gild the Black Lily?

Oh, wow… Maybe 2018? Somethin’ like that? I think 2018, 2019. But I’m always writing songs. I’m always working on some ideas. Something’s always percolating. Something is always cooking on the back of a stove. So it’s not really hard and fast. I just don’t draw a line in the sand with that stuff. It’s like a wave on the ocean coming back and forth. Do you know what I mean?

I do. You talk about the album sounding so good, the musicians playing that part. I want to talk about them a little bit. Two of the names, Boo Reiners and Hilliard Greene, are two musicians you’ve recorded with before. Tell me about working with them again, and the new folks that you’re working with for the first time in the studio.

Interestingly, all of the musicians that I’m working with on this project are all from the South with the exception of Hilliard. I think Hilliard’s from Iowa, but his parents, I think, are from the low country. He went to school in Boston, at Berklee, if I remember correctly. But I could be gettin’ all that wrong? It’s been a low-carb day! Boo Reiners is from Virginia, Shirazette Tinnin is from North Carolina, Jeff McLaughlin is from Georgia. So there’s that element. And I think that’s an important element– where someone’s coming from, their background, what’s familiar to them, and what they know. I think they brought all that to the table when they played these songs.

I’ve known Boo Reiners for so long, I don’t even remember where we met or how we were introduced! He probably remembers better than I do, but he’s just someone that plays so well and that is on the scene and that has been a fixture on the scene for so long that I really don’t remember when someone said, “Hey, this is Boo,” and I’m like, “Oh, well, hey, how do you do?” When those formal lines are drawn like I said. Like with songwriting. Things just go back and forth. I can’t remember. I honestly can’t remember! But I do know when I met Hilliard. I met Hilliard when I was singing in a big band. The first thing that struck me about him is that he can play anything! He can literally play anything. And he has a very nuanced approach to whatever you put in front of him. I could give him a three-chord country song and he would turn it into something larger than life, something, four-dimensional because he is so thoughtful and so nuanced with his playing and with his approach. It’s really difficult for me to think about music and dynamics and recording and not include him. You always wanna have someone like that on your team. You always want to have someone like that that has your back. Boo is like that in a way as well. He’s all-purpose, and he can play anything. I did a gig uptown at Minton’s, I think it was more like a Sister Rosetta Tharpe tribute. I wanted to sort of combine country and jazz and I brought him into it and it was really spectacular. That was Sharp Radway, I think? I can’t remember if he was playing piano, but I know that it was Boo on acoustic guitar and Jeff McLaughlin on electric. I believe Hilliard was on bass. But doing a lot of Sisters Rosetta Tharpe and a lot of jazz with a lot of twang underneath it– which I don’t think there’s enough of in the world (laughs)!

I agree!

Well, I don’t think that’s an outrageous thing to want because as you probably well know, the earliest recordings of hillbilly songs were really jazz musicians playing with hillbilly artists, country artists. In many instances, a lot of those hillbilly artists were black. They just advertised them differently as a marketing ploy.

I watched your TED Talk, which I just absolutely thought was amazing in how you were able to cram that history down into, I think it was just a second or two over 10 minutes!

If I had an hour, I could have changed the world (laughs)!

And I want to expand upon that in a minute. But that link that connects all of this music and the way you talk about it being a house and one day being able to own that house again… I want to talk specifically about the idea and the implementation of Black Americana and your scene and how things are going there. You’re in Harlem, right? You’re still based out of Harlem, New York City?

Yeah. I live in Harlem. I live in a really beautiful part of Harlem next to the water on the West Side that looks a lot like the Carolinas. If I could wave a magic wand, it looks like South Georgia! I could walk you over, not surprisingly, by Grant’s Tomb, adjacent to Grant’s Tomb, it’s just a wooded area, and you’d think you was in my mom’s backyard in Atlanta! It doesn’t look any different.

Tell me about the scene that you are part of, the music scene, Black Americana, and some of the things that are happening there.

Well, I’m not like the others. I do a lot of different things in New York. I play a lot of different kinds of music, you know? I sing with James “Blood” Ulmer. I’ve sung with him for a really long time, and he’s from St. Matthews, South Carolina. The sound that he’s bringing to the mix in terms of harmolodic jazz, I embraced that early on, and I embraced the Black Rock Coalition early on. They were very good to me when I first came to the city. I did showcases with them, but ultimately it was about working with a lot of different bands and a lot of different sounds. I sing with Eyal Vilner’s Big Band, I sing with Michael Arenella & his Dreamland Orchestra. You know, Michael Arenella’s from Texas by way of Georgia? He lived in Atlanta before he came to New York, and he does the Jazz Age Lawn Party every summer.

When I do my own music, I’ve got like four or five different configurations of what I do. I also sing with the Hot Toddies, which is another hot jazz group. Black Americana is something that is really intensely personal, but it’s augmented by a lot of different kinds of jazz. I would say that Black Americana for me is the sound that raised me. That is the low country, the low country church that I grew up in, the sanctified church I grew up in, which had a lot of acoustic leanings. There wasn’t a lot of instrumentation. It was just a bass drum and a lot of clapping and a lot of tambourines and syncopation. And I went to a performing arts high school in Atlanta! I went to Northside School of the Arts, now North Atlanta School of the Arts. So I did a lot of musicals. I did a lot of showcases there with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. We did Leonard Bernstein’s MASS. I did that in high school with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. So it’s a lot that’s in there that’s informing where I’m coming from. It’s not just country music and it’s not just me sitting around and listening to George and Tammy or any other country music that I was listening to when I was a kid. All the stuff that was happening on Hee Haw! There’s just so much stuff in there! I can remember when I first came to the city, running around with Chris Whitley and what that felt like and what that meant– just playing music with him on the fly!

There were a lot of southerners here after a certain point. Olu Darra is another one that I love a great deal from Mississippi who’s steeped in a lot of really wonderful American music traditions. He’s a jazz musician, but he does a lot of musical theater, and he does a lot of dance theater. He worked with Dianne McIntyre for years. So it’s a not a strict adherence to, “This is my lane.” I think a bigger part of what it means to be a harmolodic musician, as Blood would say, “You can’t play harmolodic music unless you’re a harmolodic person.” So a bigger part of what it means to be a harmolodic person and a musician is to really run around all over the place! To be into all kinds of things and have all of this overlap that a lot of people can’t understand because they’re used to pigeonholing or getting really specific about defining someone in one particular way.

More often than not, I have to explain that I do all of these things, that I’m a solo performer, and a bigger part of my story in New York is that I had to become the thing that I needed. I needed someone to co-write songs with me. I really did! And those people came and then they went. Ultimately, I had to be my own songwriter. I had to learn how to write songs by myself. I really needed someone to produce my songs. “I wish someone would come along and produce my songs!” But after a certain point, I had to produce those songs, which is me producing my last two records. It would’ve been great if some hotshot had come along– and it would’ve been great if I had the money to throw at him! And it would’ve been great if I was tied to some billion-dollar, jillion-dollar record label that’s corporate enough to slingshot my ideas out there into the world and give me all the money I need to hire whoever I want! But it’s just not working out like that for me!

I don’t know that you would have been able to do the things that you’ve done thus far musically had it worked out that way.

Exactly! That’s my next point! You’re exactly right!

I spoke to Charley Crockett recently, and he said the exact same. We got to talkin’ about artists in the ’50s and ’60s, how they basically were being taken advantage of and sold their entire lives to the record companies. His point was that they didn’t have a choice back then, and today, we do. We don’t have to do that. I feel like embracing that independent artist spirit, you’re more capable of doing it in this day and age than ever before.

Oh, absolutely! Don’t get me wrong, I’m not sad about it. Look, I remember giving my five-song EP to Alejandro Escovedo when he played Joe’s Pub, whom I admire greatly, and he took that to the folks at Bug Music. That’s how I got my publishing deal. They got bought out by BMG, so that’s who I’m with now, but that wouldn’t have happened without him running interference and saying, “Hey, listen, the songs are really good. I think she’s got something.” This is the way it’s turning out for me. And I really love it! I love living in New York City. I love that every single day is a new challenge that keeps me out of my comfort zone. There’s no room or space for me to get comfortable. There’s always something for me to learn that keeps me at an absolute beginner’s status for the most part. I am literally dancing on the head of a pin! Seriously!

The pandemic, right before it happened, I did a one-person show that I’ve been working on called Blackbirding about how, basically, the Civil War never really ended and the idea of blackbirding— which is kidnapping free black folk off the street back in the day and dragging them off to slavery– is something that’s still happening. People are still having their lives just abruptly taken from them at a traffic stop or walking down the street and looking a cop in the eye like Freddie Gray did in Baltimore. These things happen. They happen when you least expect it. You can’t predict it. There’s more to the show than that but that’s what I was doing.

And then I got a residency at Gettysburg National Military Park. I lived in a house that was built in the 1850s on the battlefield itself, a stone’s throw away from the wheat field, which is arguably one of the most active, shall we say, areas of the battlefield. That was the area where the flag changed hands more than a dozen times in the course of a day. The fighting was so thick that the bodies at the end, ultimately, were piled so high, you could walk from one end of the field to the other and your foot would never actually touch the ground. I was there for almost a month.

What did that entail? This residency?

I got to live in that house alone for a month and just let the environs of the battlefield inform whatever it was that I was creating, whatever it was that I was writing. I wrote a slew of songs that will be on the next album. I don’t really want to talk about that yet because we’re working on it.

I’m gonna pick your brain about that in a moment, but before we jump into that– or before I attempt to jump into that– I want to talk about a couple of the songs that are on this new album, the originals as well as the covers that you do. I’ll start with “The Whiskey Wouldn’t Let Me Pray”, which I think is probably my favorite song on the album. That one popped on and that’s when I stood up a little bit straighter and was like, “Oh, here we go!”

Awesome!

That one, and then followed up a little bit later by “Oleander”, which I know was not written for the year 2020 in the pandemic, but it certainly seems like it could have been.

Why do you say that?

Because it has that deep-seated, to me, depression that is looking for an answer, and the oleander leaf seems to be the only one. I think a lot of people have felt that way this past year.

Yes!

Maybe you didn’t intend for it to be a 2020 song, to me, it came across as such, which is something else that I’ve noticed a lot in this last year with people releasing music– how prophetic a lot of it seems to be.

Timing really is everything. I did not plan the timing of it to be so on the money, on the nose, but these things happen. You have to leave room for God in everything that you do. And who could have predicted? Who could have known? I couldn’t!

You brought up Sister Rosetta Tharpe earlier, another great paragon of American music period. You do “Lonesome Road”. That song goes back years and years and years and years…

Yeah! 1928, 29, something like that.

You do a rousing rendition of that one, which is completely juxtaposed against the Eagles cover that you do. And I tell you, I hate the Eagles. I really do! But hearing you sing “Take It To The Limit”… One of my coworkers, Anthony [Ennis], I made him listen to it. He is also not an Eagles fan…

You made him? Listen to you! You made him!

I did! And he and I both felt the same way! We wished that we had never heard the Eagles, so we could only hear this version.

Wow!

How do you decide the songs that you are going to interpret versus the songs that you’ve written to record?

Well, there is a through-line. If you’re really listening, there’s a through-line to all of it. When I was a little kid and I heard the Eagles… People are so passionate about how much they don’t like the Eagles!

And how much they do as well!

And how much they love them! Yeah, it totally goes both ways! I always heard [“Take It To The Limit”] in my head as a gospel song. I never really heard it any other way. And when all of the rioting and everything was going on and all the upheaval– not with the most recent upheaval with Derek Chauvin, but before that, with everything that was going on with Trayvon Martin– to me, “Take It To The Limit” was a kind of call. This is a call for us to fight for it all over again. I’m paraphrasing the Coretta Scott King quote that says every generation has to fight for freedom and equality all over again. And that’s really what that song is about. I wanted it to be a Civil Rights anthem. I wanted it, in that way, to reflect the times.

That’s an interesting concept– using the Eagles as a Civil Rights anthem.

It is, and I guess (laughs) that it feels like something that could never have been! Who could’ve predicted that? But ultimately, when a video gets made, it’s going to be footage of Civil Rights workers and unsung heroes and everything else really fighting for freedom and justice and equality. If you look at it in that way, it turns into a completely different song.

It does! I’m hearing it in my head right now and imagining all that!

Take it to the limit one more time!

Let me ask you this, this last year, when it comes to Civil Rights, when it comes to the police reform that needs to come around, when it comes to all of the death, when it comes to everything that’s happened to Black Americans in this last year… I know this is not new. It’s an ongoing thing. As you were quoting King, do you think that we just got lazy when it came to the fight? Like overall as a people, we just put it down and decided to ignore it for a little while? And now all of a sudden it’s like, “No, you can’t ignore me! The fight must be renewed!” Do you think we just got lazy?

No, I think that we live in two different Americas. I think there’s in America that people of color live in and black people live in. And then I think there’s America that everyone else lives in there. Everyone that’s white or that aspires to whiteness.

I think that’s something we’ve had to acknowledged too. For my group, that’s the hardest thing… Not the hardest thing. It’s the thing that needs to be acknowledged. That it is in fact the truth.

Yeah. The experiences that I’m having as an American aren’t anything like what you’re going through. And there’s no one that comes over here that wants to go through what I’m going through. Even the people who are here don’t want to go through what I’m going through. Nobody wants to, and no one’s willing to do anything about my having to go through this. It’s just something that everyone kind of tolerates, or they look the other way because it doesn’t affect them personally. When it affects them personally, then they’ll do something about it. And there is another generation that feels differently, I think. But I don’t know if they feel differently to the point where they’re willing to do something about it, even if it means not voting for someone who’s going to then put their foot on my neck. Because ultimately, these people weren’t born in office.

They weren’t born there and they don’t just get to stay. They’re elected. So voting them out would help! Voting for someone that has your best interests at heart would help. Voting for someone who’s taking certain things into consideration for all of us would help. That would change everything! There are certain things, certain terms that we should all understand and know. We should all understand the definition of racism and systemic racism and the difference between someone that’s racist and someone that’s prejudice. It shouldn’t be a question as to whether or not racism is real in America or whether systemic racism is real. Or if that’s just something black people say! That shouldn’t be something that we wonder about! But we’ve had decades of really bad schooling in America. We gutted the educational system. We didn’t want people to learn how to think critically or read well. This has been decades in the making. So we’ve got a lot of work to do. We’ve got a lot of work to do before all of us are on the same page. And I think that it’s possible– but people have to be willing.

There was a whole generation of white southerners who thought nothing of lynching someone like me for wanting to read! I would have gotten flogged! Would’ve gotten whipped at a tree for going to a library and asking for a book! At one point in time, that was illegal! That generation had to die before we could make a certain amount of progress– and it could very well be that another generation might have to die before we move forward, before we take a great grand leap forward. When you’ve got people like Lindsey Graham on television going, “There is no racism in America,” we have a very serious problem. Why would we have a Civil Rights movement if there was no racism in America? Why would we do that? Why would we have gerrymandering and redlining and all of these Republicans fighting for people to not really have the right to vote if there was no problem?

And why would so many people be angry in my state [of Georgia] right now if it wasn’t an actual issue?

Absolutely! We’ve all seen the footage of John Kennedy of Louisiana, the Republican, [saying] to Stacey Abrams with her voting initiatives going, “You find the bill racist? What’s so racist about this bill? Tell me, could you just list out the components that you think are racist?” And she listed out so many things, he finally said, “That’s enough, thank you.” She hadn’t even finished! She had just begun to make the list. He’s like, “Well, is that all?” She said, “No, sir, no, it is not.” And continued on until he finally said, “That’s enough.” James Baldwin said it best. We can’t really fix what’s wrong until we face it.

And that’s the problem. Too many of the powerful people don’t want to face that there even is a problem. Like somehow admitting that there is a problem means that that the world will fall apart when in fact, it would actually help put it back together. I don’t understand the reasoning on a lot of that. But let me segue into asking, is that what you’re writing about now for the next project? Without asking you to go too deep into it, is that what is informing what you’re doing now?

Yes, absolutely! My southernness and the South that I come from, I don’t really see a whole lot of it or hear a whole lot of it on the airways. And I don’t see a whole lot of it on all of the country music awards. I see Nashville and Memphis and Muscle Shoals and lots of Texas, you know what I mean? There are certainly different artists from different parts of the South, but my part of the South– Charleston, South Carolina, South Georgia– I don’t see a whole lot of that. I don’t see a whole lot of that in general. I think it’s because it’s so unapologetically African. There’s something distinctly African about the sounds that come from the Sea Islands, that come from Charleston, the slang we use… Something distinctly African about the songs that are in place. The way that we even conduct ourselves! It’s all over everything, right? It’s in the air, it’s in the food, it’s all of it!

You know, all the Southern Revival? That’s all African! That’s African cooking. That’s African captives being given by the white colonizers, the food that they knew and that they understood so that they wouldn’t eat something that made them sick. They could prepare food that they recognized. That is a mighty culinary contribution to the United States to the table. So much of low country cooking is so directly… I mean, Frogmore stew, the whole nine yards is so directly African– and it’s the same way with the sounds! It’s the same way with the blues we make and our church music, but it’s so African that I think people haven’t really figured out a way to co-opt it and that’s why it’s not as popular as let’s say, oh, I don’t know, New Orleans! We’ve got a direct line from everything all over the world. You say New Orleans and you say the New Orleans Heritage Festival, everyone has a syncopated beat going off in their head. Everyone knows what that is and it’s a top tourist destination for Europeans, of course! All things French augment New Orleans the way a lot of things that are English augment South Georgia and the Carolinas, especially Charleston.

But that’s what I’m really thinking about. I want to put certain things that are historical in a modern framework, in a modern context. I think that’s really important because I think we are living history. You have your ancestors’ blood in you just like I do. And we are not only living history, but we are living through it. We are living through the results of it. We are living through the after-effects. That’s a bigger part of what it means to be alive and in this world and functioning.