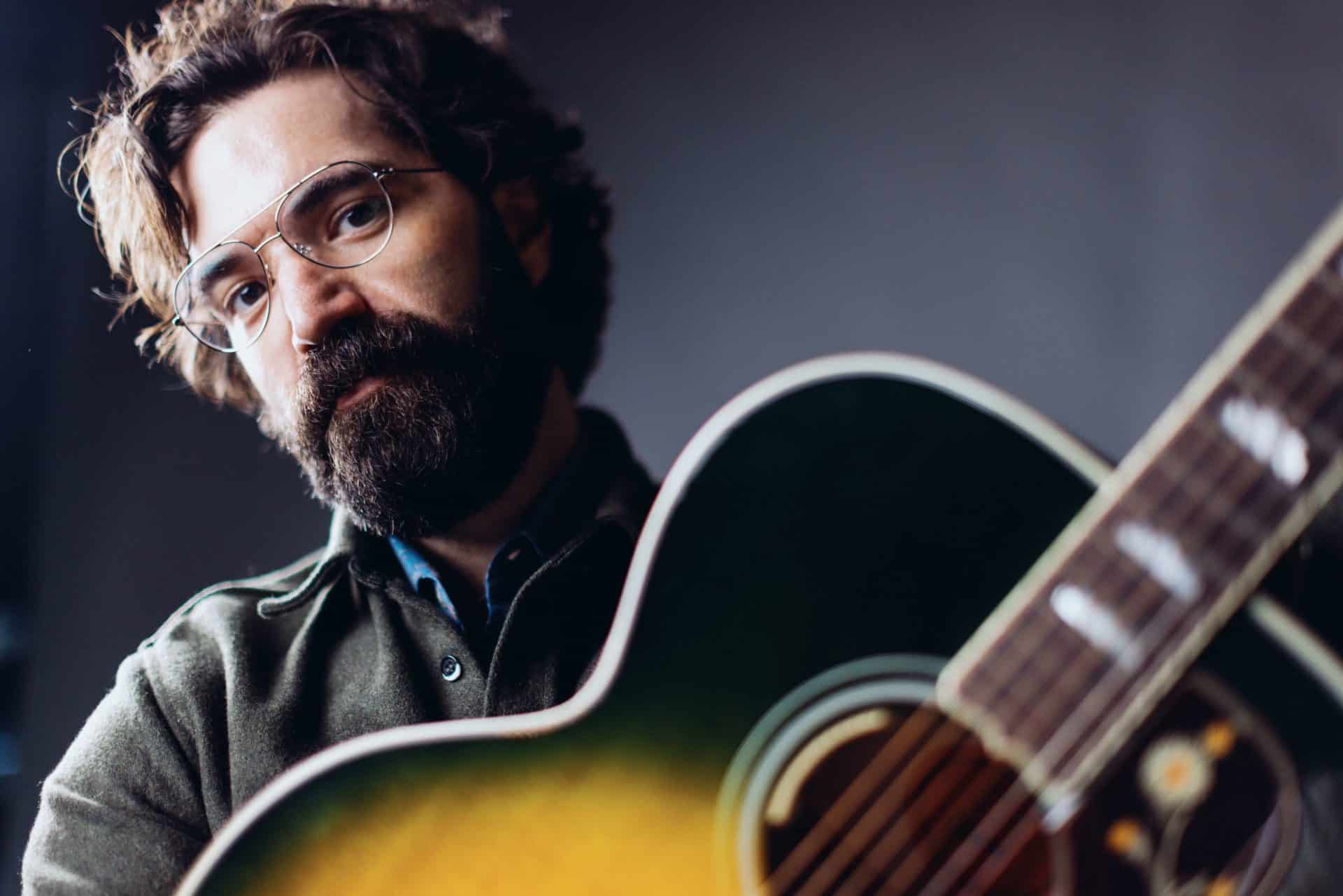

See Andrew Duhon with special guests Jennifer Westwood & Dylan Dunbar LIVE at Grant’s Lounge on Friday, February 24th! Get tickets now!

Andrew Duhon’s Emerald Blue is roux rich, darkened with earth, and textured by deceptively understated performances that pulse like nearby hearts.

Inspired sweetly by sojourns among the misty broadleafs of Washington State and tautly by his pandemic experience amid the struggling scenes outside his own New Orleans window, Andrew chain wrestles the challenges of the day, smoothly moving from hold to hold with harmony, awareness, and humility.

There’s conflict but also comfort, and the core of guitarist Duhon, percussionist Jano Rix (Wood Brothers), bassist Myles Weeks (Seth Walker, Eric Lindell), and keyboardist Dan Walker (Heart, Courtney Marie Andrews) remain surefooted throughout, their considerable abilities exemplified by GRAMMY-award winning, golden-eared engineer/producer Trina Shoemaker (Grayson Capps, Sheryl Crow).

Answering my call from the road, Andrew was able to share thoughts on his latest (and future) efforts, social media, and the evolution of songwriting.

AI- I confess that I have never spent any time in the Pacific Northwest and it’s somewhere I’ve always wanted to go. That part of the world had a profound influence on Emerald Blue and I daresay a critical influence. You were up there, but you weren’t necessarily touring– it was more of a personal experience. Tell me about that and the difference between experiencing a locale in that respect versus touring.

AD- We’re on the road right now, and folks’ll give us ideas, you know, “If you have time, do this or that,” and the fact is we never have time to do any of it! The things that we see are hotel rooms, load-in docks to venues, stages, and then another hotel room– and the van, of course! We visit these places, so to speak, but we don’t spend enough time to really get to know ’em.

But when it came to the Pacific Northwest, it was a week at a time goin’ to visit my partner, who was workin’ up there– she’s a pediatrician– and when you spend that kinda time, returning almost feels like home eventually, a feeling of familiarity with a place. What was once foreign starts to feel comfortable. The terrain, the flora, and the fauna– that’s where “Emerald Blue” comes from, mostly. It’s that blue-green water that’s completely foreign to someone who grew up around the muddy Missississipi!

You’re based in New Orleans– and you grew up in that area?

Yeah, I was a suburb kid in Metairie just outside o’ New Orleans.

I enjoy your worldview, particularly on the opening track “Promised Land”. There’s so much to unpack in that song– the myth of the American Dream, the patriarchy, immigration, and you handle it all with a compassion that I think many powers in the world would actually have us see as a weakness as opposed to finding it as a strength.

I think “Promised Land” is one of a couple o’ songs that were inspired by the social justice awakening, and the question I’m asking myself is, “What do I have to say?” As someone who comes from a place of– not fortune, but I’m not afflicted by prejudice too much. I’m a white guy walkin’ around the streets and it’s not affecting me, in the same way, it’s affecting someone else. And for that reason, that question, “What do you have to say?” was problematic, but I think the social justice awakening was the time when it was no longer “okay” to just let those who know it best speak about it. We have to speak about it together because it’s a problem we need to solve together. Those who are not oppressed are the ones who need to see it as a problem in order to affect change. “Promised Land” was specifically an act of saying, “I have never known that kind of pain. But I see that pain.” I think that’s important.

You’ve said, “Politics are not inspiring,” and I don’t find [“Promised Land”] to be a political statement, I find that to be a very human statement that often gets twisted into politics. Is that something that you see as a conflict in performing these songs when you’re out there touring?

Certainly, I think there is that issue of distilling ideas into polarized positions where we talk about politics and instead, I think we should talk about philosophy: Simple ideas and battle cries don’t solve complex problems. Sitting down to talk, sitting down to listen, more importantly, to hear what someone is seeing, admit that our own myopic view is not the only way it can be seen– it feels to me like we’re shoutin’ back and forth pretty simple things and not really talking about the complexities of them.

“Slow Down” is another song that has so many things inside of it. Talkin’ about a drive to accomplish and consume at the expense of being able to even enjoy it, many of the songs on this album were born out of the pandemic and that political and social upheaval that we were just talkin’ about– that certainly wasn’t created by COVID-19 but amplified. Many artists that I’ve spoken to, as hard as it was, they pointed to that forced downtime as a weird blessing where they actually had the benefit of slowing down. What about you? I know that you kept yourself on almost a very strict writing and streaming regimen, so did you in fact get a break? And was that what Washington state was for you?

Well, I agree that the nature of the quarantine, for me, was a proof of concept that if only I would’ve given myself that time and respite to write, I could be effective in doing so. But I still (laughs) haven’t ever given myself that time voluntarily! That’s the interesting thing about “Slow Down”– it was one of the first songs that I shared during the quarantine because it wasn’t inspired by the quarantine, it was inspired before that when I was hustlin’ and never stopping. It was a question of, “Can we just slow down and enjoy this stuff before we are gone, before it goes away, before the opportunity to slow down doesn’t exist anymore?”

But then there’s that other piece– a passion for something kinda feels like a vent more than it does a job. It’s clear to me that if money didn’t exist or I didn’t have to do anything, I would still write songs. Being cordoned off to my place in New Orleans and what I called my little “song cave”, my room with the guitars and whatnot, that is what I wanted to do is work out these tunes, all these drafts of songs that might’ve been conjured up– lines, bits, and pieces that I’ve stuffed in my pockets and brought back to the desk but then got back in the van and headed somewhere else. This was the moment to shuffle through those and start to figure out what songs were in there. It didn’t feel like work then; it felt like what I needed to do to share. And did it feel like rest? I suppose enough that getting back on the road now, I certainly don’t take it for granted and I enjoy it in a new way. So in ways, certainly, I was resting but I think also, it was important to me to continue to work on writing.

You talk about that sharing part… Through your Patreon, many of your fans had an opportunity to watch songs evolve in a very unique, inside way. How was that for you?

I admit that I am not the most social media savvy, and I think that’s a little bit of a choice. It doesn’t feel comfortable, to me, to share, wide open, my whole life. I’m carefully editing some songs to figure out what I have to say– that’s the part that I wanna share that’s intimate. The intimacy of my private life on social media doesn’t feel like what I’m choosing to share. But Patreon is a much more intimate crowd, a smaller community that is choosing to pay a monthly membership to be a part of [it], and I found that much easier to share a little more intimately the process of the songs– a draft that I knew wasn’t finished but in the wee hours of the night before I’d go to bed, I’d record a video of the draft of that song to share on Patreon because I knew they understood what I was doing, letting them into where I was with this particular song.

I think it’s a different statement to share it more widely. I think [that’s for] sharing a brand new song that you think is finished. A finished product is something I’ll share to everyone but for the Patreon community, it feels like I can let ’em into the process.

The ability to do that– social media as a whole– but that ability to connect with people very early on in a song, that’s not something that John Prine could do in the ’70s when he was travelin’ and writin’ songs with other people and makin’ his name. And even if he did, I don’t know that he would have? I think we’re seeing whole new generations of artists that see that as a genuine part of the process– starting at the beginning with their fans. Do you see that as the next evolution of songwriting?

I certainly recognize that Patreon is a piece of what feels like the evolving landscape of the independent music business that didn’t exist when John Prine was doin’ it, and that is to engage with the most active of fans, the people who are on board with whatever it is you wanna do. You wanna start paintin’ & sellin’ ’em? People are into that. You wanna do a weekly podcast? Those people are into that. They wanna know what you have to say all the time, and to engage with those folks and allow them to inspire new [material] that I wouldn’t be creating necessarily were it not for Patreon? Specifically, the podacst that I do with Grant Morris for Patreon exclusively[The Grant & Andy Podcast], I wouldn’t be doing that were it not for that community inspiring me. Engaging with the purest of fans, that smaller community, feels like the way forward in the music business. Who’s really connecting? And how do I really connect with them?

I saw a statement you made to the tune of you don’t record songs the way that you wrote them. I want an example of that, and then what brought you back together with Trina Shoemaker for Emerald Blue?

I think the process of recording, if I were to simply go into the room, the studio, with an acoustic guitar and sit on a chair and have two mics set up, that might be a fairly accurate depiction of how I wrote the tune, but I leave the possibility open for other instruments. I tour with a trio, and I hear things that I think belong in these songs, a lot o’ the classic ideas– the drum kit, the bass, the harmony vocals, the keys– but I find that when entering the studio, there’s sort of a blooming effect that happens with the songs in the sense that there’s this natural occurrence that’s a little outta your control, and it’ll surprise you where a song might go. Obviously, you can manipulate it and steer it one way or another, but some of it can be unintended and beautiful.

“Down From The Mountain” might be one that felt like a folk song put to slide but with the instruments– the accordion and the violin, in particular– it was like they created the mist over the mountains that when I closed my eyes, in my mind when I play that song, I go there. The production on that song feels like it created a scene that was only in my mind, and now I think it’s on the track. That’s credit to Trina Shoemaker, for sure, and everybody who played on the record.

I got back together with Trina partly because after the quarantine, to me, it was about putting together the [people] I felt most comfortable with and most confident that they knew exactly where I was coming from because we had traveled some road together. Trina, at the top o’ that list, we had already made two other records together, and she just understands what needs to be done at the helm of the ship navigating a particular record. If we’re in our iso booths playing our little parts, looking at the smaller pieces, she always has her eyes on the horizon steering the whole thing. I find that extremely comforting in what can be a pretty nerve-racking, precious process. You’re putting down in track form what you have created, essentially making it a static thing, where otherwise, it always moves. Every time you perform it on the road, it’s moving, it’s changing, but that track won’t change. It’s gonna be what it’s gonna be. It’s an important place to make decisions, and I feel like Trina has been the person I trust the most to help make those decisions.

As far as the album, she shares credit as producer along with Jano Rix and the rest of your trio. Bringing all that together, when you have everybody in the room working toward that sound, what is the overall dynamic? Are you able to step aside sometimes or do you have a vision that you’re trying to realize?

I think wakin’ up in the morning and listening to what we did the day before is a nice moment. Stepping away is hugely helpful, but I think compiling the group that we did– Jano and Dan Walker and Myles Weeks– all of those people know this music well enough to have valid ideas about where these songs are going, what their particular part to play in the capturing of the tune should be. That’s completely generous of Trina to offer the production credit to all of us, but there’s some validity to it because everybody really did have enough experience playing with me and recording with me that they had a notion of where we were heading and checking in to discuss that we’re all on the same page. It was certainly the least stressful recording experience I’ve had!

One of the most provocative songs, indeed if not the most provocative track on Emerald Blue is “Everybody Colored Their Own Jesus”. I love that song– and what a time to release a song like that when the very notion of being aware of the difference in how people see their God and what comes along with that expectation, I think that’s popping the stitches in America pretty severely and heavily right now. But that’s something you get to witness in real time where you’re from in New Orleans.

Most of the New Orleans kids went to Catholic school and that upbringing, I have experience with Catholicism and what that did for me. On one side, I appreciate the community fostering rituals and the ways that can bring folks together but was absolutely witness and guilty of creating an us-ness vs them-ness, which when you’re dealing with something as omnipresent as a deity, we should be able to rise above these ideas that we have the perfect vision of reality. I don’t ever remember in my Catholic days believing that I could’ve been wrong or that anything was important in our faith about questioning our position in a way that would allow us to be humble enough to see ourselves in our fellow man who didn’t believe the same thing. It’s striking to me now on the other side o’ that, and that’s why I felt it necessary to write a song like “Everybody Colored Their Own Jesus” because I think we are all coloring own realities. If we can admit that, it’s probably easier for us to both accept and coexist and learn from other peoples’ perspectives.

Has your goal for yourself as a songwriter changed with this album?

I think there was a bit of a pivot with those two ideas “What is it that I have to say?” and “Write what you know.” “Everybody Colored Their Own Jesus” is a good example of me feeling fairly confident, “Okay, I know enough in my own experience to write about this.” But the pivot is about me being less precious about the whole thing– less precious about the recording, less precious about how other folks might take this. I think I’m comfortable enough now that I’m being thoughtful in the process so the product will remain thoughtful and hopefully, it will inspire thought. But if it’s not completely squaring with someone else’s worldview, that’s okay. I would’ve been more precious about it in the past, and I think being less precious means that I think I’m opening myself up a bit more– a more natural, honest delivery of songs, of performance. I feel more comfortable with myself and whatever it is I have to say on this record or the next song.

“As Good As It Gets”, I touched on that just briefly earlier when I brought up John Prine. It’s an ode to John in many respects but also an artist’s lament. I’m making the assumption, goin’ back to “Slow Down”, that was a song that maybe predated the pandemic when you were facing the road and so busy that you couldn’t stop and focus on other things.

I found that song, strangely enough, in an old phone the night that I got word that John Prine had passed away. My first move was to pull out the John Prine records and turn the lights off and light a candle and pour a whiskey…

We had just finished up dinner. We sat at the table and got out the guitar and we played and was just bawlin’ my eyes out!

Yeah, man, that moment was necessary. But the next moment, for me, was, “Wait a minute, there’s a song I wrote where I mention John Prine– let me see if I can find it!” It was the last ditch effort, this old cracked phone I had in my desk, which I was able to power up and find that voice demo– and there it was! Otherwise, it would’ve been lost for sure! I would have never remembered it! But there it was!

It was the only song that I didn’t put into that Quarantine Songs collection of YouTube videos that actually did make the record. I shared it on Patreon exclusively, so in that way, it was almost this “Rudy” of a song that was outperforming its initial listing, and sure enough, it made the record! And I’m glad it did ’cause that is an important moment for me to point out and admit my own hunger in my pursuits. “This just can’t be as good as it gets,” is admitting my own discontent. I’m hungry for more. I wanna play to more people, you know? I wanna continue to share these songs until I’m sharing them with more people at the same time. That’s a certain amount of discontent while still being incredibly happy and appreciative of being on the road. I think both of those things are true.