When I tell Danny Beard at Wax n Facts that I’m going to talk to Amy Ray in an hour, he smiles and says, “Ah, the loud one!”

As one-half of the Indigo Girls alongside Emily Saliers, Amy Ray has been a revolutionary force for change since the mid-’80s. Much of the beloved folk rock duo’s success owes to creative tensions between bandmates, with Saliers often citing Joni Mitchell as a primary influence and Ray’s formative listening experiences– The Clash, The Pretenders, The Jam, and The Replacements– straying toward the hey-ho-let’s-go variety. Loud, indeed.

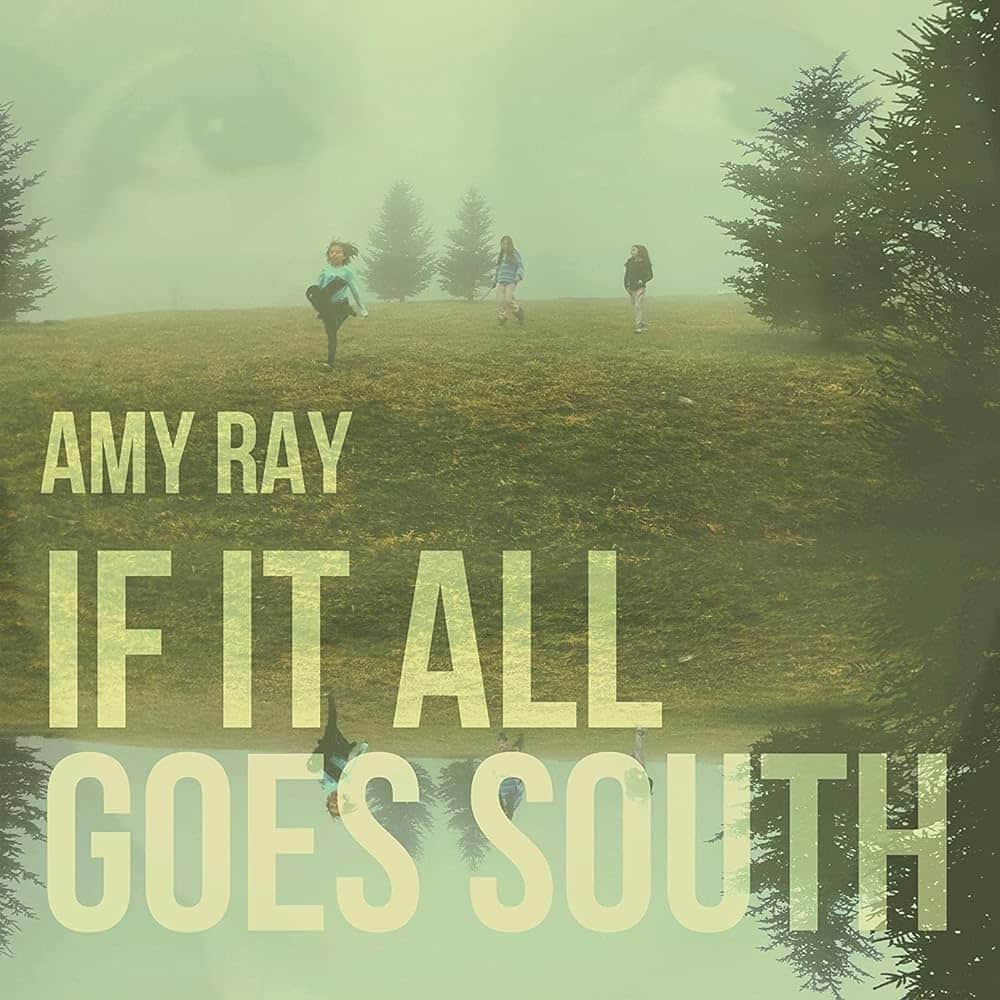

So it’s no surprise that Ray’s solo records have leaned more punk than coffee house. From her solo debut Stag (2001) to Lung of Love (2012), she delivered a string of fuzzed-out teenage kicks that were both pensive and rambunctious. Beginning with Goodnight Tender (2014), Ray began a return to a more traditional presentation, but her music has lost nothing of the our-band-could-be-your-life vitality that comes with years of touring. That connection and urgency are the heartbeat of Ray’s latest record If It All Goes South.

Recorded live to tape at Nashville’s Sound Emporium and produced by Brian Speiser, If It All Goes South is Ray’s pandemic record, a response to the hell-on-earth turmoil wrought not only by COVID but also the cultural and political unrest of the last six years. While the album is a product of a specific era, it isn’t burdened with a time stamp that renders it a relic. Instead, the album is a living document of resilience and hope that slowly reveals itself with repeated listens.

AI- When I told a few of my friends that I was talking with you about your new record, everyone– people from the Atlanta music scene, my coworkers, a friend in Dahlonega– gushed about how cool you were. You’ve made quite an impression. Did you have the same interactions or relationships with the musicians you admired when you were first playing shows?

Emily and I got lucky. We had great people in our musical lives that helped us out a lot. We met nice people. I don’t really even remember meeting people who weren’t that nice. I’m sure there were a few along the way who I can’t remember because it’s a long life, but when we started, everybody in the Atlanta and Athens scenes were pretty supportive. We hooked up early on with Kevin Kinney, and he helped us out a lot. The guys in R.E.M. helped us out a lot, and then these women we followed around– these songwriting women–were helpful, people like Caroline Aiken who would let us play during her breaks sometimes and things like that. So our experience from the start was, “Pay it forward”. People do favors and are supportive. We’ve been lucky in that way and anybody that we met was a bummer, we probably didn’t spend much time talking to them. As soon as you feel that vibe, you steer clear, and you’re the better for it (laughs)!

I just finished reading Grace Elizabeth Hale’s Cool Town, a definitive account of the Athens 1980s music scene. The concentration of talent, creativity, and enthusiasm in that little town astounds.

The “Athens” that was right before us was the coolest, with Pylon and Kilkenny Cats and Bar-B-Que Killers, The B-52’s, and all those bands. They were two years or three years maybe right before we had the chance to really play in Athens as much. But we were wide-eyed, of course, when we went there the first time because we knew everything was still pretty fresh, and REM was hitting it. It was really cool.

Did you ever feel The Indigo Girls were part of a distinct movement or scene? There was the college rock scene in the early ’80s. And then you had the 120 Minutes era and the alternative movement in the early-to-mid ’90s. It feels like you floated through all of those.

I think we rode a movement earlier on when REM gave us a chance to open for them. Early on, we were the product of college radio, believe it or not, which is crazy to think of now because college radio is formatted. It was what non-comm and community radio are now. And college radio is coming back around to that too. I’ve been listening to the Atlanta stations a bit lately, WRAS to see kind of where they’re at. We were the product first of that sort of college radio alt-scene/folk music. And then because we toured with REM, we were a part of that little world for a while. And then I think we were lucky to get into the portal of time when people were playing Tracy Chapman and that kind of female folk music. And then Lilith Fair. But we’ve ridden through a bunch of different times because… We’re old (laughs)! We’ve been around a long time, so there’s always been these moments that we’ve gotten the benefit of in some way. It’s luck and timing, half the time, being whenever there’s something good happening, taking advantage of it, putting the work in, and realizing that you’re lucky.

A number of my colleagues at Life University– Dr. Thomas Fabisiak, Dr. Tom Flores, Marie Powell, Dr. Mitch Ferguson, and Henry Hammond– are involved with The Chillon Project, which brings opportunities for higher education to women incarcerated at Arrendale State Prison. Mitch mentioned that you and Emily played a show there before the pandemic.

It was right before the pandemic, right before the lockdown of the pandemic. I was worried, actually. I was hoping that we didn’t bring it in. I know it got really bad. People I know who work in the system of incarceration and are lawyers and stuff, just the things they talked about when the lockdown started and just how hard it was in the prison system to navigate a lot of things without the resources they needed, human or otherwise. I was like, “Oh my god, I hope we didn’t.”

But, it was the greatest experience, though. Emily had worked with a choir that had come out of that prison to do some recording. That was years before this, and then we got invited to sing, and it was a great, great experience. The people were so nice, and it was great to meet the women and hear about some of their lives. You realize that with people, you pull one thread on the tapestry. and the whole thing falls apart in some people’s lives. It makes you realize how lucky you are because it doesn’t take much [to unravel]. Just to have parents and a backup support system if your life falls apart– people who would be there for you, financially or otherwise– not everybody has that.

It was fun, and the women did some performances for us. It was all very moving, very cool.

Last year, Marie hosted an event that gave some newly released women the chance to tell their stories. Their testimonies were both heartbreaking and life-affirming. I don’t know that I’ve ever experienced anything like it. It was a beautiful occasion.

I remember talking to a couple of women who had learned beekeeping and working with horses. They were getting ready to get out, so we were talking about what they were going to do with their lives. It gave me goosebumps, you know? You’re in this system that could be so depressing, but there are so many good people who work within the walls with helping people find a path after they leave and encouraging that. People just think the prison system is this void where there’s no promise. We’re sheltered, and we’re taught to think all these things. And yeah, there’s all the negative stuff about incarceration and what happens, but there’s also all these saints who work in the capacity of just helping people find a way or give them a chance. It makes you understand the other side of that, which is the beauty of promise and people’s resilience and the ability for some of these women to overcome the sadness in their life and all the stuff they’ve been through and still be positive. It’s just amazing, you know?

Have you always been civic-minded and politically driven? Or did that mentality come with age?

I guess civic-minded, first. Before anything, it was me and Emily in the early days in Little Five Points in Atlanta, looking around and saying, “Well, let’s do a benefit for the homeless,” and “Let’s do Meals on Wheels,” or “Let’s work with the people who are working with people who have HIV.” It was local, civic-minded. We were taught by our parents to give back to the community. And then it grew from there because we realized you could organize a group of people to get together and raise money for causes. Then we realized that because we were in college at Emory, we had access to copy machines and resources to achieve things, along with a whole group of people to tap into as well. We’ve always tried to leverage whatever situation we’re in to do something that’s community-oriented, whether it be something local for Atlanta or Zapatistas in Mexico. But yeah, it’s probably from our parents and maybe some teachers at our school. They taught us good things.

I was going to ask if you grew up in a politically active household…

We both grew up in households like that. It was interesting because our parents were on different sides of the political spectrum. My parents were very much in the Republican camp– the old Republican camp, not the one that’s happening now– but my dad was into Reagan, and he loved John McCain later in life. And my mom, I think, was probably more Democratic, but voted with him usually, because now that he’s passed, I can see because she votes Democrat now. We went to church all the time, and we were instilled with that idea of tithing to the community as well as the church.

Emily’s family was much more left of center, but still had the same ideas about community. My dad gave help to everyone in his extended family who didn’t have the means to go to college. He grew up pretty poor, but then he made good and became a doctor and was in the Navy and used his money to help other people. So we learned firsthand that that’s what you do. And then he always did things for people. He was always fixing people’s stuff and helping kids. He was over on the high school field, flying remote control airplanes, and everybody would come over, and he would teach them how to do it. That’s just kind of the way my parents were, just very into helping people. And Emily’s parents were the same, so it was just a little bit politically different, but the same message.

What’s your history with protest music?

A lot of my first exposure to music was through my older sister who played the Woodstock record over and over again, so I think people like Richie Havens, Janis Joplin, and Neil Young, especially when I hear that music, it reminds me of the ability to grab a guitar and write a protest song. Then I discovered Woody Guthrie. I went to church camp all the time, so a lot of the songs were singing Cat Stevens, Bob Dylan, and Joni Mitchell, some of the protesting music. I learned by virtue of that kind of folk, church tradition when I was really young and then moved on to listening to people like The Clash and Patti Smith.

So much protest music comes off as heavy-handed, or it’s so topical that it’s instantly dated. The album opens with “Joy Train”, which name drops Medgar Evers, James Brown, and the Jordan River, but the song feels timeless. How has your music avoided that fate?

They may have that fate! It’s just still current, unfortunately, you know what I mean?

I haven’t thought about it that way. I guess the hope of the protest musician is that their message or cause becomes obsolete sooner than later.

I’m writing about racism, and we haven’t overcome that. I always try to inject some humanity, because I try to talk about my own experiences, taking myself to task in my own place in the system that is dysfunctional or racist or whatever, but I also try to consider what the people on the other side of these issues feel like. Why do they feel the way they feel? We’re all humans, and we’re all trying to work it out, so I think in some ways things become more universal when you’re trying to understand other sides of it for some reason because it will cast it in a different way. It’s not so didactically of this specific time and subject. If you think about it, we’ve been dealing with prejudice since the dawn of time. And it’s like, “When will we get it right?” I guess that is the question. We may never, but we have the structure of industrialized racism and the idea of slavery and slave labor– those are things that might have come up in the way, way, way past– we don’t know for sure– but the modern day version of it is insane to me and hateful, but it’s long-lasting, and it’s lived long. I think it’s one of the last things that will fall, as far as social justice issues [are concerned]. I can almost envision there being a time, where for everyone, even in a rural area in Georgia, being gay is not a bad thing. But it’s hard for me to envision the same thing around racism right now. It just feels like we have a long road ahead. So maybe the songs will be obsolete at some point, but that’ll be a beautiful thing.

If It All Goes South is your COVID record, but of course, there’s been so much more turmoil going on. Considering the pandemic and cultural and political upheaval, is this the most tumultuous time you’ve lived through?

I mean, I guess it might be. I’m pretty old. I was born in ’64. I was born in a segregated hospital, at Grady Hospital in Atlanta. That’s crazy if you think about it, but I didn’t know that. I lived through the Atlanta child murders and knew that things were going on, and it felt tumultuous to a certain degree, but I didn’t know. When we were kids, and we would go to Stone Mountain and talk about the Klu Klux Klan having a campground there where they met still in the ’70s, I was talking about it and didn’t even realize it, you know what I’m saying? It didn’t even hit me. The impact of what was really going on did not hit me until retrospect. So I might have lived through the late ’60s and early ’70s, which to me were pretty tumultuous, and the civil rights movement was pretty violent against the people that were marching, and there were lynchings going on and there was a lot of bad stuff happening, but I was in my little white suburban bubble and knew it was happening, but the impact of it wasn’t hitting me. And we’ve worked up to this time. It’s not even just COVID. I mean, it’s the least of it compared to what else is happening.

The title If It All Goes South carries a few different meanings today, given the elections next week. It could go south, as in go to hell, or the other way, if the south goes blue…

Yeah, no, you’re right, and that is exactly what I meant. I meant both things– we’re kind of the center of a lot of things right now that could either go really good or really bad. I was talking to Brent Cobb a few months back, and he was asking me what my new record was called, and I said that, and he said, “Oh, I got a song called that,” and I was like, “Really?” I have all his records, so I was like, “I don’t remember that one.” He said, “Oh, it’s on this little demo thing I did.” He said what he meant was the exact same thing that I mean, so I thought, “Well, at least we think alike.” And that’s great because he’s got a great perspective on life, and he’s a really good songwriter. I did definitely mean both things. It was exciting for me when we had the last election and Warnock and Ossoff got into office. And we helped vote Biden in and that was really exciting. And then, of course, everything started falling apart, and you’re just like, “Oh, god,” because you want something to be consistent

Was it difficult trying to write under these circumstances, or do you flourish creatively under duress?

There’s a certain muse, isn’t it, that comes when you’re under duress. Well, two things were happening. One thing is that I was at home, so I had a lot of time to contemplate in between doing chores and my kid’s remote school learning and just trying to keep up with everything, which was busier than I would have thought it was. I was like, “I’m so busy for not having any work.” That’s how I felt. But for me, on this record, you could definitely tell that I was thinking about social justice stuff but also thinking contemplative thoughts about human nature. It wasn’t hard to write. This was not a hard record to write for me.

But also, I have this band that I’ve been with for nine years. We’re really good friends now. It’s like six guys, and they range in age from like 25-70, so we have a really broad experience, as far as the way they inspire me. We’ve traveled around in a van a lot because that’s how we tour. When I’m thinking about a record now, because I’m with them, they’re part of my muse, actually. So I’m thinking about them musically, thinking about my guitar player and what he would play, and the banjo player, Alison Brown, who always records with us– she doesn’t tour with us, but she records with us. She’s in my head when I’m writing sometimes. I think for me, this record was in a great way the product of traveling so much with this one band and feeling them musically and then having a lot of stuff going on that I wanted to talk about. That’s basically what these songs are: I just needed to talk about this kind of stuff, and I’m lucky that I get to make it into a song.

Do you write with live performances in mind? For instance, “A Mighty Thing” catches a southern rock groove, and “They Won’t Have Me” has plenty of space for extended jams.

I did think about that. For me, when I do solo music, I don’t usually go at it alone. I’ll do a rare show where it’s me all by myself, but I hate doing that. Usually, it’s me and Jeff [Fielder] or the whole band. With “They Won’t Have Me”, we were all as a band thinking about this song, and we were like, “Oh, this would be really fun to do live, like if we just started acoustic and changed to all electric instruments.” When we were in the studio, we had to do it completely choreographed live, so we did it start to finish completely live, which wasn’t hard for us, but the control room had to change all the input gains for the whole structure of everything as we were changing instruments because we were going to tape, and the acoustic guitar was going into an electric guitar, but on the same track of tape, so their side of it was like a nightmare. We have a film, a really cool sped-up video of Bobby [Tis] the engineer changing all the gains while we were changing instruments, and it was insane!

But yeah, we think of how we’re gonna do things live and how fun it will be to play something live. I also think about the body of material that we already have that we play live, because sometimes I’ll think about that when I’m writing and think, “Oh, my god, I’m not gonna write another ballad. We already have so many!” I’ll think, “Ok, that song I’m gonna put aside for something else that we’ll do later. But for this record, I wanna have a certain kind of song, a certain kind of show, a certain kind of experience while we’re taping and everything.” It’s all like about collaboration at this point and who plays in the band and musically where they’re coming from. Since we’re kind of a band band that really operates together, I think about the music as much as I do the lyrics. I think there might have been a day in my life when I thought about lyrics more, but there was a time, probably even as much as twenty years ago where I decided I needed to focus on music and start thinking about melody because that was really weak for me. So now with this band, in particular, it’s really helped me because they’re all such good players, so I can go to them and say, “I want to do this thing, but I don’t know how to get there chord-ally, I just know how to get there melodically, and they’ll help me, which is nice.

I read that you found inspiration in Stephen King’s On Writing and Ann Lamont’s Bird by Bird. Are there other resources you’ve come across that have helped you as a writer? You’ve mentioned that you write more slowly than Emily. Is that a source of frustration for you?

I’m not frustrated by it anymore. I used to be. There were two songwriters that we joked around about. One of them was Emily, and the other is a guy named Gerard McHugh. We’d say that if you were at a party with either one of them, they’d go into the restroom, and they come out and have three songs written already– like they’re so fast and good. Emily can just sit down literally and write a song. I know she spends longer than that now because she’ll say, “I can do that, but I like to spend more time revising than I used to,” which I think is good. But for me, it’s just what I’m used to now. I look at it as a blessing in some ways because, by the time I finished the song, there’s been enough time for me to look back at it and say, “Is this like completely irrelevant to me now as a singer? Can I still get in that place? Is it still for me personally a song that I wanna write?” So that’s good.

There was also a book called Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg that’s instructive with exercises that you can do. But really Bird by Bird and On Writing are still my go-tos of what really changed my whole approach. And I think now also there are certain songwriters like Justin Vernon from Bon Iver and Madison Cunningham and H.C. McEntire, as far as newer people. There are certain writers that I look at lyrically and musically, and I study what they do, like, “How did Justin get from this place to this place musically and lyrically, too?” He’s such a pioneer of our time. I think he’s one of the visionaries of our time. So I really still use that. And then I read a lot, so a writer like Louise Erdrich and the way she uses language is inspiring. And then sometimes I’ll go back and read [William] Faulkner’s books, or I’ll read Flannery O’Connor for the umpteenth time.

I spent a lot of time in Milledgeville as a student and teacher, so I know O’Connor quite well.

Well, my mom’s in all of her books somewhere or another (laughs)!

Can you talk a bit about the song “From This Room”? You’ve said that it’s a song that ended up being for your daughter. She’s eight, and you’re fifty-eight, so there’s the reality that you won’t be around when she reaches those critical moments later in her life. I’m 44, and my daughter is almost 2, so I immediately identified with the sentiment and the reality.

Yeah, it’s a weird thing to think about. Also, I keep a diary for my daughter. You should think about doing that. You know where the idea came from? The show Sons of Anarchy. You know how Jax used to always sit on the roof and write letters to his kid in a little book because he was afraid that he would die right? And because he was going to. But I thought that’s what inspired me to start keeping a diary for Ozilline because she’s going to be at an age where she’s really figuring life out, and I won’t be here anymore. So yeah, as I finished that song, that’s definitely what I was thinking about.

The song contains the lines “Anyone can sing this song / it’s been written a million times.” I suppose that’s the reality of songwriting, poetry, and literature. At their core, the works are variations of the same universal stories. So why do we return to art over and over again? Also, how do you keep your songs fresh and interesting?

Well, I don’t know if I keep it interesting to anybody else but me…

Are there other artists you have in mind who make it new?

I don’t know because I think we have our archetypal things as humans that we always return to. And I agree– I think it’s because we’re in this constant existential struggle with mortality and human relations and “What is love?” and “How do you love?” and “What is hate?” and “What does that mean?” We have these problems that are the essence of who we are, and they’re always going to be here, and situational things are going to come up over and over again. But I think the way that you keep it relevant and fresh is that your images are detailed and unique and true to you, and you write about what you know, right? The greatest writers to me are the ones that tell a universal story, but in a really detailed, unique way that makes you interested in it. My favorite poet is Frank Stanford, and his images kill me. They cut to the bone, but he’s writing about things that we all think about, but he’s putting them in the lives of these people that are characters that are so rich in imagery and description that you can see yourself in them, or it’s like you’re watching a movie. It’s like a carnival sometimes; his writing is unbelievable.

So I try to look at those great writers and think, “What are they doing?” because it’s a universal message, but they have this detail that’s catching you off guard, so you’re paying attention to it and it’s getting into your heart because the descriptions are so rich. Flannery O’Connor did the same thing, and so did William Faulkner. I’m very into Southern writers. I can’t help it, but that’s what I’m into. And also a lot of African American writers, Tony Capen Barr and Audre Lorde, where there’s so much description that you almost can’t even follow it, and you have to go back over and over again and reread it. I love those writers.

The song “Subway” is a tribute to the late Rita Houston, a DJ at WFVU and host of The Whole Wide World. She’s known as “The Tastemaker of the World” and was an early champion of the Indigo Girls. Who are some of your own tastemakers from your childhood?

I had an English teacher named Ellis Lloyd– and Emily had him too, along with all my siblings– who taught an advanced placement English course, and he completely changed my life by showing me what is in words and what’s important when you read and how to read. He turned me on to literature that I would never have even thought about. And then I had a history teacher, Warren Sutherland, who was a coach as well, and with his take on history, he tried to teach us things that weren’t in the textbooks. I would argue with him all the time about everything because I thought I knew stuff that I didn’t, and he’s the one that made me think– like really made me think– about history and what we were taught and what we weren’t taught, more importantly.

So those two people illuminated my life, and I had a youth minister, Reverend Bo Blasingame, who had been a chaplain in the army. He was really rough around the edges and kind of a hardcore, no-frills sort of a guy, but super kind. He was really influential to me too, just about human nature and how to treat each other and how to think critically about faith. That was important to me because I was raised going to church a lot, so I needed to be more critical.

Musician-wise, I had a lot of songwriting conversations with Steve Earle, because I really would go to him, struggling with songwriting and how to write and this and that, and he would say things like, “If you want to write, you just have to write, Amy. You just have to sit down and do it.” I really needed to hear that because I was so lazy sometimes. Those are some of the people in my life, but there’s so many. It’s amazing.

We talked a bit about the South and art. Your song “Tear It Down” deals with dismantling the Southern cultural institutions, including Gone with the Wind, Song of the South, and the “celebration” of all things Dixie. Were you quick to find this iconography problematic, or did that realization come over time? I ask because I never experienced that one galvanizing epiphany. My journey was much more gradual. For instance, I grew up with my family reading the Uncle Remus stories, and I was slow to understand these weren’t just stories, that they carried some serious baggage, to say the least.

No, I had the same experience. I mean, even in college, I thought the Confederate flag was cool. I thought it was badass, like, “We’re Southerners, and we’re rebels.” I had no idea; I just did not. I even thought that even while I was thinking about how bad racism was. It took me to probably even after college. I took an African American lit course in college at Emory, and the professor was amazing. And the Atlanta Child murders had just happened. She was an activist and was on the inside and knew a lot that had gone on during that. And I think her class is the thing that changed me and made me understand that I needed to start thinking about things differently.

It took me a while to separate myself from those symbols. And I think of my grandparents, too, because I’m from five generations of my mom’s side of Southerners, of Georgians. And my dad’s side was Florida, Georgia, and Alabama, and that’s in Kentucky. So that’s a lot, and I didn’t want to let go. We always went to see Song of the South at the Fox Theater every year, and I loved Gone with the Wind. It was so hard for me to not fall in love with the romance of that. And I’m still obsessed with the Civil War. I’m still obsessed with the history of this area, right? And so for me to separate the bad sort of symbolism from just the sheer interest in history is still hard.

Did you ever bristle at being labeled a Southern artist?

No. In fact, I always love that. When I think of Southerners, I think of punk and Danielle Howle and The Rock*a*Teens and Kelly Hogan and all the great Southern Atlanta artists and Kevin Kinney and REM. And then Atlanta has a super rich hip hop scene. To me, it’s a great thing to be a Southern artist. I’ve never minded it.

I love the South– but I don’t like the racism, and I don’t like the classism or any of that stuff. I don’t like that people from other areas belittle Southerners and think that we aren’t smart and make fun of the accent and distill us down to this caricature of who we are.

At this point, I think each state or region has its own fringe group and figurehead– a Lauren Boebert, for instance–who reduces their state to an instant caricature, so maybe that Southern stereotype is losing its relevance.

Yeah, that’s true. No, you’re right. You’re right. Everywhere you go, there’s a character.

You frequently write about Christianity, as well. “A Mighty Thing” from this record comes to mind. I’m not sure of your beliefs, but religious or not, you’re from what Flannery called the “Christ-haunted” South, so it’s inescapable. How do you reconcile the beautiful parts of Christianity with the hypocrisy and prejudice?

I love the church. I was raised in the Methodist church, and I loved it. And I loved church camp and church choir and bible school. I loved every part of it. I went to church all the time, on Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday. Then sometimes I would to church retreats and to camp. I went to Camp Glisson, which is in Dahlonega, for four years when I was a kid. It was hard for me when realized I was gay and felt in opposition to the church I went to. That was hard for me because I was like, “Oh, okay.” In the South, that construct is part of our lives unless you’re Jewish or Hindu or Buddhist, or even Catholic. The Protestant sort of Southerner gets into anybody, even if they don’t go to church, because it’s part of our vocabulary, it’s part of everything. It’s part of every parade and every school. In every football game, there’s a prayer. You can’t escape it, and for some people, that’s very hard for them, but for me, it’s what I’m used to, so I just kind of filter it all.

But I think what I did is one day I said, “I want to untangle all the bad things that church did to me as a gay tomboy and I want to keep the good things,” and I guess the good things are easier to hang on to than the untangling of the bad things sometimes. So I just keep trying to remember the good stuff because there’s a lot of good that came out of what I learned. But there’s a lot of damage that was done to myself and my image of myself. I hated myself for so long for being gay, and I was pro-life for a long time and then became pro-choice because I realized what it meant as a woman. It’s just taken me a long time to wrestle with it all.

Have you ever been tempted to leave the South? I mean, you’ve been all over the world…

Never. Not one moment in my life have I ever said that I don’t want to live here. It’s kind of weird, but it’s true. I have places that I love, like Berlin. I love Berlin, Germany. I love Seattle, Washington.

The album ends with the hopeful “North Star”. I’m not trying to impose a narrative on the record, but did you want to leave on a positive note? Are you an optimist?

No, I’m an optimist. I’m a weird combination of cynicism and optimism, but those are different sides of the same coin in some ways. I always have hope because I do believe in the inherent goodness of most people– of 99.9% of people. I don’t know what to do with that other weird percentage, like Hitler or whatever. There are always these outliers where you’re like, “Well, they’re probably not inherently good.” I’ve also been around a lot of really good social justice work, too, that has given me a lot of hope, especially with the Native American stuff that we do, where we work with all these tribes and support their efforts to do really good things for the environment and cultural sustainability for their tribe and all the other tribes. I’ve seen these success stories that have been remarkable– I mean, really remarkable– like winning against huge corporations on big things like nuclear waste. So that gives me hope.

And then I get hope from just being around cool people, like even where I live in Dahlonega. There are these different characters here that do these amazing things. There’s one guy and his wife that have a farm, and they have dinners every Saturday where they talk about what we can do to improve the community. They have music, so it’s like a salon. I’ve been once, but I read about him and I think that’s so cool that this person and his wife do this. And there are people that are doing a river clean up. It’s these little pockets of hope that are always happening.

I’ve seen people change. Like my parents– they were not down with the gay thing at all. And I’m one of three sisters that are all gay, so that was a tall order for my mom and dad. They were disowned by some of their best friends. It was an uphill battle for them. My dad passed eight years ago, but before he died, he was so supportive of people that were gay, to the point of being an activist about it, like going to the preacher at church and saying, “You can’t fire the gay organ player. He’s the best thing at this church.” It was really heartening. And then my mom, too. I’ve seen people in my community change, people who were really anti-gay and racist. Everything about them was, to me, not loving. I’ve seen people change, and I know it can happen. It doesn’t happen because you attack someone. It happens because you are patient with people and show them kindness. That’s when it happens.

Obviously, the political situation is so hard because you just want to scream and say, “Everybody, just sit down and eat a meal together!” so they can figure out where we’re coming from and try to get along, but it’s just not that easy, is it?

I think we’re drawn to art because we learn something about ourselves when we encounter another person’s work. But we also learn something about ourselves from our own work. Have you learned anything about yourself as you revisit songs from If It All Goes South?

I’m always learning about myself because I’ll say something and reflect back on it and be like, “Well, that wasn’t…” I’m just like every other human, I’ll leave a situation where I was talking to somebody, and then the language I used was not quite right or it fell into a racist trope that I didn’t even think about.

From this record, I learned a lot just when we recorded it. I had little moments. My drummer [Jim Brock] is amazing, and he’s had a lot of experience. He’s 70, and he’s played in a million different situations. He’s the wise guru of the band and he keeps our beat. I constantly was saying, “Hey, I think we’re going too slow or too fast,” just arguing about tempo, to the point where I was looking back on it– I mean, we get along; the band is like family– but there were a couple of moments where he was totally right and I was wrong, and when I listen to the record now I think, “Oh, man, he was really right about that.” (Laughs) Recording this record has definitely taught me about better ways to discuss things! I’ve learned about my temper and being quick to decide something about an arrangement before I’ve really thought about it or when my ego gets in the way. I think the process of recording is really good for people, especially when you record live. It’s a tape, and you can’t change things, and you’ve got to learn that dissent in the studio is not healthy. If you want to achieve the recording that you want, everyone’s got to be supportive of each other. I thought I knew that, but I learned it, even more, this time.